|

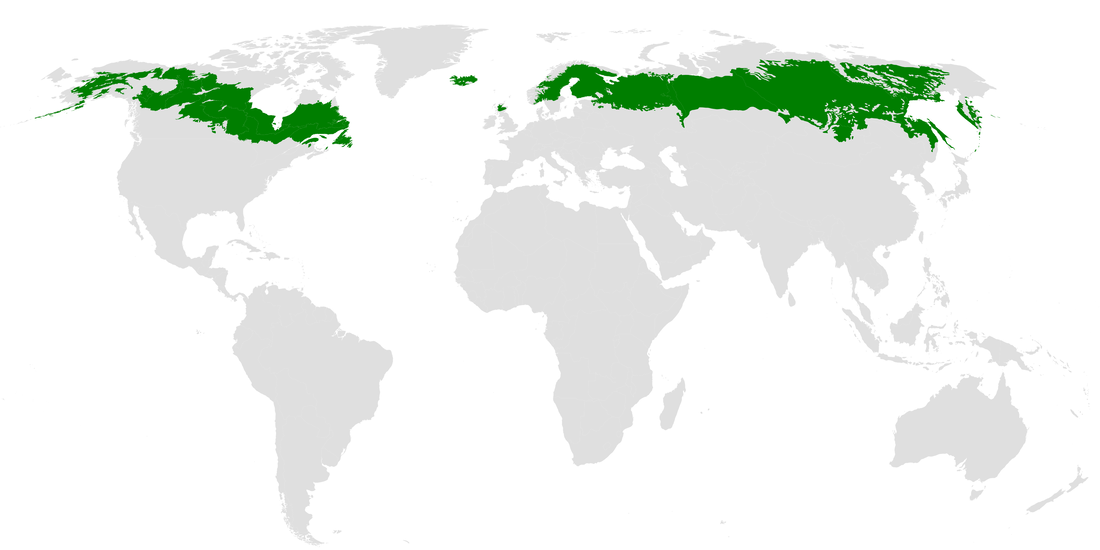

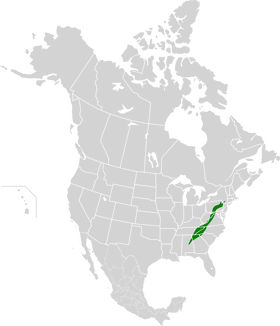

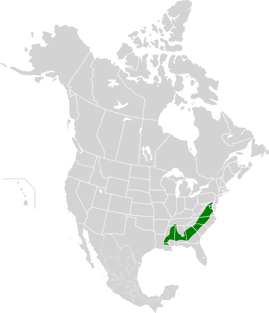

by Jeff Stehm We are often caught up in the here and now, or at best, think only in human time scales. But have you ever wondered about what Shenandoah National Park looked like millennia ago or might look like a millennium in the future? Shenandoah National Park today hosts a rich Appalachian Oak forest consisting of hickory, maple, and tulip poplar, with oak as the dominant tree species. Pine predominates on warmer southwestern faces of the southernmost hillsides. In cooler areas with northeastern aspects, small, dense stands of moisture loving hemlocks exist. The average annual temperature in the Park is about 46.5°F at Big Meadows (located in the north central area of the Park), and ranged from about 44°F to a little over 50°F over the last 75 years. Forty-five thousand years ago it was a very different place. North America was in the midst of the last throws of the ice age. Temperatures fluctuated (over centuries) from cold to warm and back again. Litwin et al. (2004) estimated that the mean annual temperatures around Big Meadows varied about 20°F over the 45,000 year period, ranging from about 35°F to 55°F. In today’s climatic terms, these variances in temperature was equivalent to those existing today from latitude 55°N (Northern Newfoundland) to 32°N (Georgia). Such temperature swings profoundly affected the forests of Shenandoah National Park. The Park experienced temperatures almost 10°F colder to 5°F warmer – enough to shift forest biomes drastically back and forth between cold artic boreal forests and warm Oak-Hickory-Pine and Southern Mixed forests. Forest biomes shifted back and forth a minimum of 37 times during the last 45,000 years as shown below. Forest Type Years Ago Climate Boreal 45,000-37 000 Cold Northern Hardwoods 36,000-35,000 Warming Northern Harwood-Spruce 32,000 Cooling Boreal 28,000 Cold 27,000 Last Glacial Maximum Northern Hardwoods 26,000 Warming Boreal 25,000 Cold - Northern Hemisphere Insolation Minimum Northern Hardwood-Spruce 24,000 Warming Boreal 22,000 Cold NE Spruce-Fir 17,000 Cool 15,000-13,000 Warming - Bolling-Allerod Interstadial Warming Northern Hardwood-Spruce 13,000-12,000 Cooling - Younger Dryas Cold Pulse Pleistocene-Holocene Boundary Appalachian Oak 10,000-6,000 Warming Southern Mixed 6,000-4,000 Warming Appalachian Oak 4,000-present Cooling Source: Adapted from Litwin et al., 2004. Climate is continuing to change in Shenandoah National Park. Average temperatures in the SNP are expected to shift upwards any where from 1.7°F to 12.7°F depending on the climate model, assumptions, and baseline years. By the end of the century, temperatures are likely to exceed the upper end of the historical range of the last 45,000 years. In addition to temperature changes, annual precipitation is expected to increase from 1.5 to 8.5 inches by the end of the century. The future climate at the Park, therefore, is likely to include on average milder winters with fewer frost days, hotter summers, and wetter and cloudier conditions. As a result of these climate changes, Shenandoah National Park is likely to evolve from an Appalachian Oak biome to a Southern Mixed Pine biome. This may mean a loss of species such as maple, eastern hemlock, northern red oaks, yellow poplar, beech, and other northern hardwoods, and an increase in hickory, sweet gum, shortleaf and longleaf pine, loblolly pine, various elms, and southern oaks (National Park Service, 2015b). Appalachian Oak Forests Southeastern Mixed Pine Forests

Source: Wikipedia Source: Wikipedia But climate changes are occurring faster today than they did 45,000 years ago. Temperature and precipitation changes that occurred in the past over thousands of years are occurring today in less than 100 years. In the short term this is likely to:

For example, native brook trout are a cold-water fish. Park officials have measured warmer stream temperatures in recent years, which could put the brook trout under stress and may ultimately eliminate or greatly reduce their numbers in the Park (Saunders, et al., 2010; Flebbe, et al., 2006; National Park Service, 2017a). Another animal that may become a climate change casualty is the Shenandoah salamander, an endangered species that is found nowhere else on the planet. About a quarter of bird species and 10 percent of the mammals in the Park will likely shift their ranges into and out of the park as the result of either direct or indirect climate effects (National Park Service, 2019d; Wu, et al., 2018; Burns, et al., 2003). Some mammal species, such as the red squirrel and the southern red-back vole, are particularly sensitive to climatic conditions and may be lost to the Park (Burns, et al., 2003). Species reshuffling, however, may result in a net gain to the Park, as more species move into and colonize the Park than move out. So when you next consider the Good Ole Days, think longer term, both in terms of the past and the future. References Burns, C. E., Johnston, K. M., & Schmitz, O. J. (2003). Global climate change and mammalian species diversity in U.S. national parks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(20), 11474–11477. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1635115100 Flebbe, P. A., Roghair, L. D., & Bruggink, J. L. (2006). Spatial Modeling to Project Southern Appalachian Trout Distribution in a Warmer Climate. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 135(5), 1371–1382. DOI:10.1577/T05-217.1 Litwin, R. J., Morgan, B., Eaton, L. S., & Wieczorek, G. (2004). Assessment of Late Pleistocene to recent climate-induced vegetation changes in and near Shenandoah National Park. USGS OFR 2004-1351. DOI: 10.3133/ofr20041351 National Park Service (2019d). Projected Effects of Climate Change on Birds in U.S. National Parks, Briefing Note. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/climatechange/upload/01-NPS_Overall_Project_Brief_508Compliant.pdf National Park Service. (2017a). Climate Change Impacts at Shenandoah National Park. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/nature/climatechange.htm National Park Service. (2015b). Climate, Trees, Pests, and Weeds: Change, Uncertainty, and Biotic Stressors at Shenandoah National Park. Project Brief. Saunders, S., Easley, T., & Spencer, T. (2010). Virginia Special Places in Peril: Jamestown, Chincoteague, and Shenandoah Threatened by Climate Disruption. The Rocky Mountain Climate Organization and NRDC. Retrieved from http://www.rockymountainclimate.org/images/VA_SpecialPlaces.pdf Wu, J.X., et al. (2018). Projected avifaunal response to climate change across the US National Park System. Plos One, 13(3): e0190557. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190557.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |