|

Terrence McCoy

Washington Post, April 15, 2020 RIO DE JANEIRO — It's not easy being a baby sea turtle, hatching into a human's world. Curious children, leashless dogs, oblivious joggers: The dangers are many. Some never complete their postnatal dash to the ocean. But in recent days, environmentalist Herbert Andrade has watched hundreds of baby turtles mosey their way toward the water along Brazil’s northeast coast, unmolested by people or pets, unencumbered by anxiety. The beach is empty. People, fearful of catching and spreading the coronavirus, are inside. But outside, Andrade sees a natural world blooming. “The whole world is under risk,” said Andrade, environmental manager for the city of Paulista. “But this was a moment of happiness. It was a feeling that nature was transforming itself.” For centuries, humans have pushed wildlife into smaller and smaller corners of the planet. But now, with billions in isolation and city streets emptied, nature is pushing back. Wild boar have descended onto the streets of Barcelona. Mountain goats have overtaken a town in Wales. Whales are chugging into Mediterranean shipping lanes. And turtles are finally getting some peace. Buffalo walk on a mostly empty highway in India last week. (Getty Images) While some stories of animal invasion that have gone viral have been fake — turns out elephants didn’t get drunk on Chinese corn wine and pass out in a tea garden — the apparent resiliency of the natural world is leavening a global tragedy with brief moments of wonderment. For people. And, apparently, for animals, too. “The goats absolutely love it,” said Andrew Stuart, a resident of Llandudno, Wales. He saw the goats stroll into town one recent night, and has watched since then as they’ve availed themselves of its offerings. They’ve munched on windowsill flowers. Convened in parking lots. Strutted down emptied streets. “They keep coming back, multiple times per day, 10 to 15 of them,” he said. “They’re taking the town back. It’s now theirs. Nothing is stopping them.” But beyond the short-term benefits that human quarantines have brought the animal kingdom, conservationists say the pandemic could be an opportunity to push for more environmental protections and create a safer world for animals. An infrequently uttered word is beginning to sneak into conversations among conservationists and animal rights activists. “I am hopeful,” anthropologist Jane Goodall told The Washington Post. “I am. I lived through World War II. By the time you get to 86, you realize that we can overcome these things. One day we will be better people, more responsible in our attitudes toward nature.” A growing body of research has suggested that the risk of emerging diseases, three-quarters of which come from animals, is exacerbated by deforestation, hunting and the global wildlife trade, particularly in exotic or endangered species. One of the major vehicles for the transmission of novel diseases from animals to humans are wildlife markets, in which exotic animals are kept in cramped and unsanitary conditions. They have been linked to both severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and covid-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus. Now countries around the world are under growing pressure to act. China, whose insatiable demand for animal parts drives much of the global wildlife trade, has taken the extraordinary step of banning the consumption of wild animals, and may do the same for dogs. Vietnam, another country with a large demand for animal products, said it intends to follow suit. The U.N. biodiversity chief has called for a global ban on wildlife markets. So have 60 members of the U.S. Congress. More than 200 of the world’s leading conservation groups have asked the World Health Organization to take action against the wildlife trade. A World Wildlife Fund survey of 5,000 people in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia found 90 percent supported government closures of unregulated wildlife markets. “Humans are extraordinarily selfish,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a Brookings Institution scholar who studies wildlife trafficking. “If they start dying, they will start taking actions to minimize their dying. The most impactful and consequential legislation always comes after the health risks.” The impacts of the closures and crackdowns, if they persist, will be global, undercutting the demand that fuels illegal wildlife trafficking, an illicit trade valued at more than $23 billion annually. The ripple effects of enforcement in Asia could be felt as far away as Latin America, where jaguars and turtles are hunted and killed to meet demand in China. “Asian traders call it the Latin tiger,” Felbab-Brown said. “They are using jaguar bones and teeth to produce elixirs. . . . It’s picked up a lot in Latin America.” Mountain goats roam the streets of Llandudno, Wales, last month. The goats, who live on the rocky Great Orme, are occasional visitors to the seaside town, but a councilor told the BBC the herd is now drawn by the lack of people and tourists. (Christopher Furlong/AFP/Getty Images) But analysts say the pandemic also heightens potential dangers for animals. Poverty and hunger, exacerbated by lockdowns and disruptions in food supplies, may drive more people to hunt. “And that’s okay,” said Joe Walston, a senior official with the Wildlife Conservation Society. “If people are put in a position of poverty, and we have failed providing economic alternatives, they should be able to do that.” More concerning, advocates say, is the possibility that people could abandon their pets, out of the mistaken fear they can spread the virus, or because they can no longer afford to feed them. “It is more likely to increase pet abandonment,” said Marco Ciampi, president of Brazil’s Humanitarian Association of Animal Protection and Well-Being. “And the fake news is terrible. But even with this, animals will be in a more safe position, if we listen to the call of animals: ‘We are here, and if the environment is friendly, we are friendly, too.’ ” “It’s an amazingly magical moment,” he said. “There are peacocks in the streets.” Bruce Borowsky, a videographer in Boulder, Colo., was walking through the main pedestrian strip of the college town last week when he experienced that magical moment. Up near the top of a tree, beside a building, he spotted a mountain lion, asleep, back paws hanging down. Down below, Pearl Street, which normally teems with restaurant patrons, shoppers, and University of Colorado students, was a “ghost town.” Nothing was waking up the mountain lion anytime soon. “I’ve lived in Boulder for 30 years, and I’ve never seen a mountain lion before,” Borowsky said. “And I’m a filmmaker and am outdoors constantly. Animals are sensing that people aren’t around much and are coming out more. “We’re waiting for the bears to come out of hibernation and see how brazen they get.” Along Brazil’s northeastern shoreline, Andrade is also seeing sights he has never witnessed. He has cared for endangered sea turtles for more than a decade, and has seen all sorts of calamities befall them. Artificial light along the beach especially confuses the turtles. They mistake it for the water’s reflection, wander off toward it and die along the way. “For every thousand,” he said, “only one or two reach adulthood.” For years, he has tried to teach people about the fragility of baby sea turtles — an ongoing effort he compared to a boxing match. He has erected protective areas around their nests. He has held events to show children why they’re special. Life was getting better, safer for turtles. But nothing compared to this: an empty beach. For him, the beauty of it ached. “It was a surreal sensation,” he said. “You see nature living out its role in this way. . . . Things fit together. We saw nature birthed without human interaction.”

0 Comments

Here are several interesting things you might try doing from your home with your local bugs.

Photographing Bugs - The Basics Click Here More on Photographing Bugs Click Here Home Bug Projects for Kids Click Here And don't forget insect conservation Click Here By Amanda Heidt

Science, Apr. 8, 2020 , 1:45 PM Monarch butterflies raised in captivity rarely survive the species’ grueling, nearly 5000-kilometer migration. Now, researchers think they know why. When the insects were raised in indoor cages, they grew up paler (an indication of poor health) and 56% weaker (as measured in a grip strength test), researchers report today in Biology Letters. The reason may be that, although most butterflies survive when raised in captivity, only the strongest survive in the wild, The New York Times reports. The researchers don’t discourage hobbyists from raising monarchs, but they say it may not be the best way to restore dwindling populations around the globe. Also See Number of monarch butterflies wintering in Mexico down by more than half March 27, 2020 by PamKamphuis

The Piedmont Virginian By Joe Lowe When it comes to abundance, the stars we see at night (approximately 5,000) shine dimly compared to the number of plant and animal species in Virginia’s Piedmont, which may exceed 20,000, although the real number — if ever known — is almost certainly larger. If that’s surprising, it’s because the “big” species we usually see, like oak trees and deer, take up a lot more space in our minds than they do on a species roster. In reality, “small” organisms — fungi and insects, among others — represent life’s greatest diversity, numerically dwarfing their larger counterparts. These organisms, big and small, are never far. On a short walk, we might come across dozens or hundreds. Pill bugs, sumac bushes, and crows, for example, may not seem terribly interesting or consequential, but the Piedmont’s flora and fauna — known collectively as its biodiversity — are an absolute necessity for the area’s human residents. Working together, plants and animals keep soils fertile, pollinate fruits and vegetables, produce fresh air, keep water clean, and help regulate climate. In short, they maintain a local life-support system without which the Piedmont would be a wasteland. Although most of the region may look like a model of rural health, we know that its plants and animals are under intense pressure. How? Because species like the Rusty-patched Bumblebee and Purple Fringeless Orchid are telling us in the clearest way possible: by disappearing. And they are not alone. Once common birds like the Common Nighthawk, Northern Bobwhite, and Eastern Whip-poor-will are now scarce in the region. Other species are gone. Since European colonization, Virginia has likely lost 72 species. In the Piedmont, another 59 are in serious decline — more than at any other time in modern history. Some of these species range outside of the Piedmont and their downturns can’t be blamed entirely on local changes. Their dwindling numbers are symptomatic of a much larger problem. Human alterations to the planet have forced extinction rates into overdrive, reaching levels not seen for the last 65 million years. And if trends continue, half the world’s total plant and animal species could be facing extinction by the end of the century. This wouldn’t be a loss just for wildlife enthusiasts, it would be a loss for everyone who depends on traditional economic and agricultural practices. Like biodiversity itself, threats to flora and fauna vary by continent and region. In the Piedmont, there are many challenges, but experts agree that several rise above the others. Habitat Loss, Fragmentation, and Degradation During winter, local Wood Ducks spend months living in frigid water, impervious to conditions that would send us scrambling for shelter. Even so, we dismiss the feat with four words, “They’re used to it.” But what happens when “it” — the circumstances that animals and plants are accustomed to — change? Like us, their survival depends on a few basic requirements: food, water, shelter, and space. And when these conditions – known as habitat — deteriorate or disappear, they follow suit. In the Piedmont, this happens in several ways. The first, and most obvious, way is when habitat is destroyed for new construction. While some counties do a better job of restricting urban expansion than others, this has not stopped forests and fields from being converted into roadside malls, roads, and residential areas. New homes, of course, aren’t without greenspace; they have yards. But for wildlife, a well-manicured lawn, at best, offers little food, water, or shelter; at worst, it poses mortal risks when sprayed with pesticides, which kill pollinators like butterflies and bees. Multiplied across the landscape, habitat loss has a fragmenting effect, breaking large forests and grasslands into a patchwork of small, distinct spaces. In the Piedmont, these usually take the form of isolated woodlots among surrounding farms. Although they may look fine, these forests lack the critical mass necessary to maintain long-term health. They’re susceptible to invasive species and other threats, and slowly break down as their natural communities deteriorate. Habitat health isn’t just a forest issue. Given that farms cover much of the Piedmont, agricultural practices have a big impact on local biodiversity. Eastern Meadowlarks and many other grassland birds, for example, rely on local pasture for nesting sites. This can have deadly results, though, when fields are hayed before chicks fledge. Similarly, removing streamside forests and allowing cattle to graze and defecate in waterways is detrimental for aquatic species. The Dwarf wedgemussel, a freshwater mollusk, is already gone from Fauquier County, and eleven other mussel species are threatened in the region. Invasive Species If you think you know your neighbors well after a few years, imagine the relationships local plants and animals have after living together for millennia. These connections helped form a community that has flourished, in part, thanks to a natural system of checks and balances, maintaining native populations at sustainable levels. The Piedmont’s natural equilibrium, however, is in growing trouble thanks to the human-introduction of invasive species that don’t play by local rules. These species outcompete natives and multiply to nightmarish levels, upending the ecological fabric of our natural communities. They come in many forms. A fungus from China, the Chestnut blight, decimated the Piedmont’s Chestnut trees in the first half of the twentieth century. More recently, insects like the Emerald Ash-borer and Wooly Adelgid have begun killing off our Ash and Eastern Hemlock trees. Meanwhile, more than 80 species of invasive plants have besieged the Piedmont, sending destructive ripples throughout the food chain. For example, while caterpillars feast on native plants, they can starve on invasives. This means lower reproduction rates for Eastern Bluebirds and other songbirds that depend on caterpillars to feed their chicks in invasive-dominated areas. Making things worse, invasive plants have found unlikely allies among our native White-tailed Deer. Thanks to human influence, deer populations have surged across the Piedmont in recent decades — and their impact has been dramatic. Not only do deer inadvertently spread the sticky seeds of some invasive plants, their voracious grazing threatens the health of native forests and plants. Protecting the Piedmont’s Biodiversity Despite the challenges, local citizens and organizations are actively working to protect the Piedmont’s biodiversity. Piedmont landowners have put nearly 500,000 acres under conservation easement, protecting it from development. But there is still more to do and plenty of ways to make an impact. Create and Improve Habitat Most of the Piedmont is privately owned, which means that landowners have a large role to play in protecting biodiversity. Doing so is probably easier than you think. For starters, next time you feel compelled to tidy your lawn, relax. By leaving leaves, saving snags, and mowing a little less, you can improve habitat for local wildlife. If you want to do more, remove invasive species and plant natives. Remember, when it comes to protecting biodiversity, everything counts: a single oak tree can feed and provide shelter for hundreds of species. If you’re interested in a conservation easement or would like to improve wildlife habitat on your property, the Piedmont Environmental Council can help. If you own a farm and would like to protect streams and improve livestock health, reach out to the local Natural Resources and Conservation Service or John Marshall Soil and Water Conservation District for support. The Virginia Department of Forestry can also provide stewardship recommendations to improve the health of your woodlot. Learn More Many organizations offer educational programs for children or adults. These include The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Friends of the Rappahannock, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy. For more intensive training, sign up for the Virginia Master Naturalist training program. The Virginia Native Plant Society provides excellent online resources and the Virginia Department of Forestry offers identification guides to local trees and shrubs. Volunteer Locally Volunteering to support land stewardship and citizen science efforts is a great way to get involved. Opportunities are available with The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Friends of the Rappahannock, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Blue Ridge Center for Environmental Leadership, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy. Special Report:

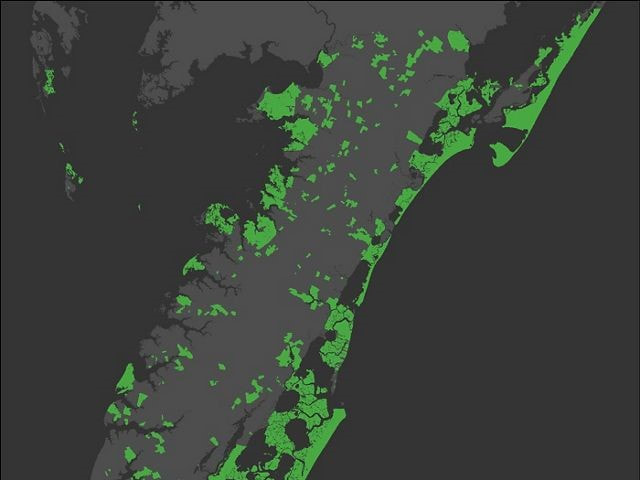

JEFF COX, APR 7, 2020,Horticulture online A few decades ago, I wrote Landscaping with Nature (Rodale Press, 1991), a book about gathering inspiration for home landscaping by going into wild nature and noting what was aesthetically pleasing, then finding ways to bring those inspirations home. I didn’t know it at the time, but I only had half the story. It takes an incredible 6,000-9,000 caterpillars to raise one clutch of chickadees. The other half is to create those natural home landscape designs with native plants. There are so many good reasons to do so, chief among them is the lifeline that native plants throw to native fauna, especially insects and birds. A true champion of this notion is Douglas Tallamy, a professor in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware. “You might think we gardeners would value plants for what they do. Instead, we value them for what they look like,” he says. He has worked to educate us on the merits of native plants and conservation that starts in our gardens through his books Bringing Nature Home (Timber Press, 2009) and Nature's Best Hope (Timber Press, 2020). Most of us know some of the things that our plants do: produce oxygen, build topsoil, prevent erosion and flooding, sequester carbon dioxide, buffer extreme weather, clean our water and shade our houses. But it’s their ability to turn sunlight into food for all of earth’s creatures that’s supremely important, especially in the context of local ecologies. One summer, Professor Tallamy did a simple experiment. He counted the number of caterpillars on a native white oak in his yard and compared it to the number of caterpillars he found on a nearby ornamental Bradford pear, an Asian native. “I found 410 caterpillars on the white oak comprising 19 different species, and only one—an inchworm—on the Bradford pear,” he said. Why such a huge difference? Native insects have co-evolved with native plants. To avoid predation, plants load their tissues with nasty insect-repellant chemicals, but the native insects have developed ways to de-fang those chemicals, usually with enzymes. The Bradford pear is a relative newcomer, and there are no insects that have yet evolved the ability to eat it—except maybe that inchworm. “In the past,” he says, “we thought this was a good thing. After all, Asian ornamentals are planted to look pretty, and we certainly didn’t want insects eating them. We were happy with our perfect pears, burning bushes, Japanese barberries, golden rain trees, crape myrtles and all the other foreign ornamentals.” Then he pointed out the ecological cost. “If you have a pair of nesting chickadees, watch what they bring to the nest to feed their hatchlings: mostly caterpillars. It takes an incredible 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars to raise one clutch of chickadees. “What we plant in our landscapes determines what can live in our landscapes. An American yard dominated by Asian ornamentals doesn’t produce nearly the quantity and diversity of insects needed for birds to reproduce. We have 50 percent fewer birds than 40 years ago, and some 230 species of North American birds are at risk of extinction,” he said, citing the 2014 State of the Birds Report. “By the way,” Professor Tallamy says, “you might assume that my oak was riddled with unsightly caterpillar holes, but not so. Since birds eat most of the caterpillars before they get very large, from 10 feet away the oak looked as perfect as the Bradford pear.” He adds that since almost all native insects have specialized relationships with native plants, planting non-natives reduces biodiversity. For example, very few insects other than the juniper hairstreak butterfly can eat the tissues of the eastern red cedar without dying. So if we don’t include cedars in our landscapes, we lose the hairstreak. “And the only host for the great fritillary butterfly is the native violet,” he points out. “When violets are mowed down, we lose the fritillaries. And if we lose the insects, including spiders and moths, we lose amphibians, bats and rodents. Even the fox eats insects—25 percent of his diet is insects.” In his book written with Rick Darke, Living Landscapes: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, Professor Tallamy tells the story of the Atala butterfly, a native of South Florida that once thrived on its sole host plant, Zamia pumila, a native cycad. The butterfly disappeared as the cycad was harvested to near extinction to make starch from its roots. But in the mid-1970s, landscape designers rediscovered it as a valuable evergreen that could take drought and heat. As it started showing up in more and more South Florida yards, the Atala butterfly returned. “Maybe it had been harbored in the Everglades or somewhere, but adding that single plant brought the butterfly back,” said Professor Tallamy. Horticulture columnist Jeff Cox writes from his home in northern California. The Virginia Coast Reserve is the longest stretch of wilderness along the nation’s entire Atlantic coastline. As it embarks on its next half-century, the Virginia Coast Reserve stands out as one of the most important living laboratories in the world, having piloted community-based conservation, contributed landmark migratory bird research and pioneered techniques for restoring critical habitats such as oyster reefs and seagrass meadows, the Virginia Coast Reserve continues to produce groundbreaking science and innovative conservation. Read about it HERE.

|

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |