Judy Edmunds collecting water sample for brook trout eDNA project; Credit: Alan Edmunds Judy Edmunds collecting water sample for brook trout eDNA project; Credit: Alan Edmunds On June 10th, Old Rag Master Naturalists, including Judy and Alan Edmunds, along with members of Trout Unlimited, Friends of the Rappahannock and other volunteers worked with Shenandoah National Park's (SNP) Supervisory Fish Biologist, Evan Childress to collect the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of brook trout. The purpose of this project was to gain a comprehensive understanding of brook trout population in the Shenandoah. This was done by collecting water samples from over 80 streams in the SNP. The process of collecting the samples was an all-day project! Volunteers first picked up sample kits at one of the two testing stations in the SNP. Along with their kit, volunteers were given a site number, a data sheet to fill out and directions to the site. Some of the sites were a long hike into the park and took some tricky trekking to get to the exact spot on the stream that was listed on the site sheet! Once the longitude and latitude were confirmed and verified, following the collection protocol, the volunteers collected 2 liters of water from the site and filled out the data sheet. After hiking back to the car, the water was put on ice in coolers to keep the DNA from degrading on the drive back to the testing stations. When volunteers returned the samples and data sheets, the park staff used special equipment to filter each sample of water. Each individual filter was then put in a vial to be sent to a lab that will use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the DNA signal. This will enable them to detect any trout DNA present in the sample. The results of the eDNA project will be long lasting. The information that was gathered will allow park biologists to not only understand the health of the streams and the distribution of brook trout in the park, but will also help park biologists make informed decisions about future conservation initiatives. Evan’s plan is to make an interactive map where people can see the results from the places we sampled and to give a virtual presentation talking about what we learned from the project. The eDNA project will be wrapping up this fall, but Evan is already looking to get additional grants to drive more projects that will support healthy streams in the Shenandoah. Stay tuned for more opportunities to help Evan in the future!

0 Comments

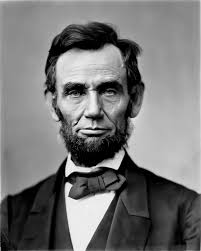

The little things that we do every day have a huge impact on our natural world. It makes sense that native plant enthusiasts care about invasives, clean water, soil health, the warming climate, more intense weather patterns, even clean air…but what about dark skies?

Dark skies affect multiple natural processes. For example, many crops are dependent on insect pollination. If you like to eat, you care about insects and in turn, also dark skies. Insects also serve as a food source for many species. If you care about birds, you care about insects and also in turn, dark skies. Why should we do something about light pollution? Humans “around 80 percent of all—and more than 99 percent of people in the US and Europe—now live under light-polluted skies. In addition to direct lighting from urban infrastructure, light reflected from clouds and aerosols, known as skyglow, is brightening nights even in unlit habitats.” (Kwon, 2018) Many, truly do not know what unlit skies look like. In addition, insects are impacted by light pollution. The article “Light Pollution is a Driver of Insect Declines” discusses how artificial light serves as an evolutionary trap. Artificial light is a human-induced problem. Throughout ecological history, “most anthropogenic disturbances have natural analogs: the climate has warmed before, habitats have fragmented, species have invaded new ranges, and new pesticides (also known as plant defenses) have been developed. Yet for all evolutionary time, the daily cycle of light and dark, the lunar cycle, and the annual cycle of the seasons have all remained constant. insects have had no cause to evolve any relevant adaptations to artificial light at night.” (Avalon et al, 2020) Insects are attracted to the ultrabright unnatural lights and exhaust themselves before engaging in pollination or reproduction. The decline of insects lead to diminished food sources for larger organisms. Light pollution causes disorientation and exhaustion in migratory birds. Birds use energy stores to make long journeys. Studies show that “migrating birds were disoriented and attracted by red and white light (containing visible long-wavelength radiation), whereas they were clearly less disoriented by blue and green light (containing less or no visible long-wavelength radiation).” (Poot et al, 2008) The good news is that humans can put ecological practices in place to mitigate the impacts of light pollution. Further research shows that “artificial light at night impacts nocturnal and diurnal insects through effects on development, movement, foraging, reproduction, exhaustion and predation risk.” (Borges, 2022) It is estimated that light pollution is driving an “insect apocalypse” resulting in a loss of around forty percent of all bug species within just a few decades. There are multiple reasons to care about insects. We can make an impact on this serious problem. Community members can have their voices heard by participating in their local HOA meetings and completing surveys conducted by the local government in the comprehensive planning phase. By speaking out residents can weigh in on light ordinances in public spaces. Even talking to neighbors who are unaware of the problem can help. The International Dark Sky Association (https://www.darksky.org/) has great resources for educating yourself and others about light pollution. Virginia has five Dark Sky parks which are more than any other state East of Mississippi. The parks include Rappahannock County Park, Sky Meadows State Park, Staunton River State Park, James River State Park, and Natural Bridge State Park. The link to the parks can be found at https://www.darksky.org/our-work/conservation/idsp/finder/. Visiting Dark Sky parks and taking part in citizen science is an important way to help protect these amazing spaces for future generations to enjoy.  BY JASON MARK (SIERRA CLUB) | JUN 24 2020 ON JUNE 30, 1864, Abraham Lincoln sat at his worktable, with its view of the half-finished Washington Monument and the Potomac River, and went through his daily routine of paperwork and correspondence. There were many issues to occupy the president's mind. The Union army had recently been walloped in the Battle of the Wilderness, Congress was debating a sweeping Reconstruction Act, and he had just dismissed his conniving treasury secretary. Among the minor matters on Lincoln's desk was a bill that Congress had just passed with scant debate, the Yosemite Park Act. The law promised to preserve for common enjoyment "the 'Cleft' or 'Gorge' in the Granite Peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains … known as the Yosemite Valley" along with the "Mariposa Big Tree Grove" of sequoias. Some 38,000 acres would be "held for public use, resort, and recreation … inalienable for all time." The president put his pen to paper and brought into being the first landscape-scale public park in history. Read on with this interesting article on our public lands. |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |