Pileated woodpecker; Photo: Deanne Lawrence Pileated woodpecker; Photo: Deanne Lawrence Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County The Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is the largest woodpecker in North America. We have several on our farm and they are amazing to watch in flight. Their exaggerated swooping and their large body make them easy to identify. But they are not related to pterodactyls – they just give that impression with their size and “jack-hammer” approach to bug hunting. These woodpeckers live in Virginia year-round and, unlike most other birds, they will defend their territory all year as well – not just during breeding season. According to Birds of North America (an amazing publication of The Cornell Lab of Ornithology), Pileateds prefer an oak-hickory forest with mature stands of dense vegetation near the ground. They have a long-extensible, pointed tongue with barbs and sticky saliva. They use their tongues to extract ants from tunnels in rotting wood. A pair of pileated woodpeckers needs a large amount of land – around 150 acres or more – to raise their young. The Pileated, like most woodpeckers, nest in hollow trees or vacated nest cavities. They excavate only the entrance hole to gain access to the hollow interior of a tree. They often have multiple entrances holes, so they have an escape route if a predator enters the roost. We have not seen the Pileated’s nest site on our farm yet but we know it is in a heavily wooded area in a steep ravine at the back of our property. They play a vital role in forests like the one adjacent to the north side of our farm. They excavate large nesting, roosting and foraging cavities that are then used by all sorts of other birds and mammals. That can include wood ducks, bats and flying squirrels. Scientists have noticed that Pileated woodpecker numbers increase in areas with widespread emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle that kills ash trees. That could mean that these woodpeckers could be one of the strongest lines of defense to control non-native forest pests. So leave those dead and dying trees out there for these wonderful woodpeckers. They’ll improve the habitat and attract all sorts of wildlife to your property. Birding tip: You can often tell the difference between a Pileated and other woodpeckers by their drumming, without even seeing it. Most woodpeckers drum at a steady pace. A Pileated drums slowly, accelerating and then trailing off. And as Audubon notes, “their loud, escalating shrieks bring to mind a maniacal laugh. " So true! Happy birding! Charlene Uhl

0 Comments

Credit: Rebeca Sanchez-Burr Credit: Rebeca Sanchez-Burr Hello and thank you for reading my blog! My name is Rebeca, I’m a land manager working on 130 acres of private property in Madison County and a member of Class X of the Old Rag chapter of the Virginia Master Naturalists. I work year round managing and controlling invasive plant species in diverse landscapes and would like to share with the Old Rag community some of my knowledge and experience through an educational series of journal entries emphasizing best practices, methods, and tools for the control of alien plant invaders. I am also the chapter liaison for the VMN EDDMapS project, which is a statewide initiative to document the spread and distribution of exotic plant invaders. One particular focus of the EDDMapS project in Virginia, in partnership with Blue Ridge PRISM, is the invasion into natural areas of exotic plants that are commonly used in conventional landscaping. It is my hope that these journal entries will also inspire the Old Rag community to gather and submit data on invasives using the EDDMapS application. Asiatic False Hawksbeard Part 1 For my first entry, because it’s April and I know everybody is super motivated to go outside and pull weeds, I’d like to talk about an emergent threat: Asiatic False Hawksbeard (Youngia japonica). Asiatic False Hawksbeard is a biannual with a late Spring to Summer phenology in the Northern Virginia Piedmont. This plant overwinters as a rosette and sprouts yellow flowers usually from a single stalk. Asiatic False Hawksbeard grows in full sun as well as deep shade and is tolerant of very moist conditions along stream banks and boggy areas. In disturbed areas, this plant can form dense carpets though in the understories of forests, you are more likely to encounter scattered plants and patches. This plant often arrives in gardens from contaminated nursery stock, advances to nearby lawn turf and is then spread by the mower or weed trimmer to other landscaped areas and eventually to forest/field edges and other edge habitat. The challenge of controlling invasive Hawksbeard in forests and fields is the multitude of small, runty individuals, which can only be located when the plant begins to flower in late Spring. It is thus best controlled getting well ahead of it in Winter and early Spring by searching and destroying large, easily identifiable rosettes and waiting for late Spring to pull up the runts, which by then have broken through the leaf litter. Control efforts in infested wilderness areas should be directed at reducing density over the widest possible area, preventing the spread to unaffected areas by targeting the perimeters and searching and destroying satellite plants and patches.

By Bonnie Beers

Reposted from November 2020 We wanted to create a low-growth meadow in a 3 acre area near our house. Ever hopeful and loath to use chemical sprays, we decided to give this former hayfield a chance to show its stuff. The site had been mowed for hay with little improvements for decades, at least. It was bordered on one side by a small stream and woods border, on a 2nd side by a deeper wood, and on the remaining sides by our driveway and the mowed/planted areas around our house. Along the woods edges, we found natives like sumac, dogwood, redbud, locust, pine and cedar, and hardwoods. We also found a patch of ailanthus, a good bit of autumn olive and some encroaching vines like Japanese honeysuckle and oriental bittersweet. Read On - Click Here What is an invasive species? An invasive species is "an alien species whose introduction does or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health" - click here for more

Spotlight on a local invasive species: Garlic Mustard - click here The cost of invasives, read this article - click here Look up invasive species and lots more at this cool website - click here March 27, 2020 by PamKamphuis

The Piedmont Virginian By Joe Lowe When it comes to abundance, the stars we see at night (approximately 5,000) shine dimly compared to the number of plant and animal species in Virginia’s Piedmont, which may exceed 20,000, although the real number — if ever known — is almost certainly larger. If that’s surprising, it’s because the “big” species we usually see, like oak trees and deer, take up a lot more space in our minds than they do on a species roster. In reality, “small” organisms — fungi and insects, among others — represent life’s greatest diversity, numerically dwarfing their larger counterparts. These organisms, big and small, are never far. On a short walk, we might come across dozens or hundreds. Pill bugs, sumac bushes, and crows, for example, may not seem terribly interesting or consequential, but the Piedmont’s flora and fauna — known collectively as its biodiversity — are an absolute necessity for the area’s human residents. Working together, plants and animals keep soils fertile, pollinate fruits and vegetables, produce fresh air, keep water clean, and help regulate climate. In short, they maintain a local life-support system without which the Piedmont would be a wasteland. Although most of the region may look like a model of rural health, we know that its plants and animals are under intense pressure. How? Because species like the Rusty-patched Bumblebee and Purple Fringeless Orchid are telling us in the clearest way possible: by disappearing. And they are not alone. Once common birds like the Common Nighthawk, Northern Bobwhite, and Eastern Whip-poor-will are now scarce in the region. Other species are gone. Since European colonization, Virginia has likely lost 72 species. In the Piedmont, another 59 are in serious decline — more than at any other time in modern history. Some of these species range outside of the Piedmont and their downturns can’t be blamed entirely on local changes. Their dwindling numbers are symptomatic of a much larger problem. Human alterations to the planet have forced extinction rates into overdrive, reaching levels not seen for the last 65 million years. And if trends continue, half the world’s total plant and animal species could be facing extinction by the end of the century. This wouldn’t be a loss just for wildlife enthusiasts, it would be a loss for everyone who depends on traditional economic and agricultural practices. Like biodiversity itself, threats to flora and fauna vary by continent and region. In the Piedmont, there are many challenges, but experts agree that several rise above the others. Habitat Loss, Fragmentation, and Degradation During winter, local Wood Ducks spend months living in frigid water, impervious to conditions that would send us scrambling for shelter. Even so, we dismiss the feat with four words, “They’re used to it.” But what happens when “it” — the circumstances that animals and plants are accustomed to — change? Like us, their survival depends on a few basic requirements: food, water, shelter, and space. And when these conditions – known as habitat — deteriorate or disappear, they follow suit. In the Piedmont, this happens in several ways. The first, and most obvious, way is when habitat is destroyed for new construction. While some counties do a better job of restricting urban expansion than others, this has not stopped forests and fields from being converted into roadside malls, roads, and residential areas. New homes, of course, aren’t without greenspace; they have yards. But for wildlife, a well-manicured lawn, at best, offers little food, water, or shelter; at worst, it poses mortal risks when sprayed with pesticides, which kill pollinators like butterflies and bees. Multiplied across the landscape, habitat loss has a fragmenting effect, breaking large forests and grasslands into a patchwork of small, distinct spaces. In the Piedmont, these usually take the form of isolated woodlots among surrounding farms. Although they may look fine, these forests lack the critical mass necessary to maintain long-term health. They’re susceptible to invasive species and other threats, and slowly break down as their natural communities deteriorate. Habitat health isn’t just a forest issue. Given that farms cover much of the Piedmont, agricultural practices have a big impact on local biodiversity. Eastern Meadowlarks and many other grassland birds, for example, rely on local pasture for nesting sites. This can have deadly results, though, when fields are hayed before chicks fledge. Similarly, removing streamside forests and allowing cattle to graze and defecate in waterways is detrimental for aquatic species. The Dwarf wedgemussel, a freshwater mollusk, is already gone from Fauquier County, and eleven other mussel species are threatened in the region. Invasive Species If you think you know your neighbors well after a few years, imagine the relationships local plants and animals have after living together for millennia. These connections helped form a community that has flourished, in part, thanks to a natural system of checks and balances, maintaining native populations at sustainable levels. The Piedmont’s natural equilibrium, however, is in growing trouble thanks to the human-introduction of invasive species that don’t play by local rules. These species outcompete natives and multiply to nightmarish levels, upending the ecological fabric of our natural communities. They come in many forms. A fungus from China, the Chestnut blight, decimated the Piedmont’s Chestnut trees in the first half of the twentieth century. More recently, insects like the Emerald Ash-borer and Wooly Adelgid have begun killing off our Ash and Eastern Hemlock trees. Meanwhile, more than 80 species of invasive plants have besieged the Piedmont, sending destructive ripples throughout the food chain. For example, while caterpillars feast on native plants, they can starve on invasives. This means lower reproduction rates for Eastern Bluebirds and other songbirds that depend on caterpillars to feed their chicks in invasive-dominated areas. Making things worse, invasive plants have found unlikely allies among our native White-tailed Deer. Thanks to human influence, deer populations have surged across the Piedmont in recent decades — and their impact has been dramatic. Not only do deer inadvertently spread the sticky seeds of some invasive plants, their voracious grazing threatens the health of native forests and plants. Protecting the Piedmont’s Biodiversity Despite the challenges, local citizens and organizations are actively working to protect the Piedmont’s biodiversity. Piedmont landowners have put nearly 500,000 acres under conservation easement, protecting it from development. But there is still more to do and plenty of ways to make an impact. Create and Improve Habitat Most of the Piedmont is privately owned, which means that landowners have a large role to play in protecting biodiversity. Doing so is probably easier than you think. For starters, next time you feel compelled to tidy your lawn, relax. By leaving leaves, saving snags, and mowing a little less, you can improve habitat for local wildlife. If you want to do more, remove invasive species and plant natives. Remember, when it comes to protecting biodiversity, everything counts: a single oak tree can feed and provide shelter for hundreds of species. If you’re interested in a conservation easement or would like to improve wildlife habitat on your property, the Piedmont Environmental Council can help. If you own a farm and would like to protect streams and improve livestock health, reach out to the local Natural Resources and Conservation Service or John Marshall Soil and Water Conservation District for support. The Virginia Department of Forestry can also provide stewardship recommendations to improve the health of your woodlot. Learn More Many organizations offer educational programs for children or adults. These include The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Friends of the Rappahannock, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy. For more intensive training, sign up for the Virginia Master Naturalist training program. The Virginia Native Plant Society provides excellent online resources and the Virginia Department of Forestry offers identification guides to local trees and shrubs. Volunteer Locally Volunteering to support land stewardship and citizen science efforts is a great way to get involved. Opportunities are available with The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Friends of the Rappahannock, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Blue Ridge Center for Environmental Leadership, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy.  Fire ants, shown here, resemble garden-variety ants, making them difficult to spot, experts say. (U.S. Department of Agriculture) Fire ants, shown here, resemble garden-variety ants, making them difficult to spot, experts say. (U.S. Department of Agriculture) By Jeremy Cox on March 18, 2020, Bay Journal In Virginia, climate change is about as welcome as ants at a picnic. But across a portion of the state’s southeast, ants are part of the problem. Since 1960, the annual average temperature in Virginia Beach, the region’s most populated city, has risen about 3 degrees, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That warming trend has opened the door for fire ants — normally living in more southerly areas — to gain a stubborn foothold in the state, Virginia agricultural officials say. And it’s growing larger. “It’s an unfortunate side effect” of climate change, said Eric Day, a Virginia Tech extension entomologist. “We have warmer winters and warmer summers, so it certainly makes for good conditions for fire ants.” The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services announced in December that it was expanding its fire ant quarantine to five new counties and two separate cities. With the addition, the quarantine now spans one or two counties deep along the North Carolina border from just west of Interstate 95 east to the Atlantic Ocean, an area nearly the size of Connecticut. The quarantine applies to both the black and red fire ant varieties, but the red is more commonly seen in Virginia, officials say. Both damage crops and deliver a nasty sting. Since their accidental transmittal from South America to the United States in the 1930s, red fire ants have spread across most of the Southeast from the marshy tip of Florida to the windswept plains of Oklahoma. When the first fire ant infestation was discovered in Virginia in 1989, agricultural officials blamed the interstate trade of plants and sod. They grew so widespread that by 2009 the state announced its first quarantine in the Hampton Roads region. It has become clear with their continued spread westward along the state’s southern border in recent years that colonies are now marching up from the South on their own, Day said. That shift points for the first time away from humans as a cause for their proliferation in the state and toward a new climate reality, he added. Fire ants resemble garden-variety ants, making them difficult to spot, experts say. Tell-tale signs of their presence are their mounds, which can reach up to 2 feet high and damage farm equipment. The ants themselves prey on corn, soybeans and other crops, causing further headaches for farmers. Their sting, though, may be their defining attribute. Anyone who unwittingly wanders into a nest typically emerges with a foot or leg stippled with burning welts that turn into itchy, white pimples that last for days. In extremely rare cases, the victim can suffer deadly anaphylactic shock. Christopher Brown, who works in purchasing and product development for the Lancaster Farms plant nursery in Suffolk, knows the sensation all too well. “It’s not like getting stung by a bee where it’s one sting and that’s it,” he said. “When you get bitten by a fire ant, you’re going to get bit five to 10 times depending on how long it takes you to realize you stepped on a fire ant mound.” Suffolk was one of the first areas to be quarantined in 2009. The designation prohibits transporting anything that can carry fire ants out of the area unless it is certified as ant-free. Regulated items include gardening soil, plants, sod, used farm equipment and freshly cut timber. At Lancaster Farms, workers blend an insecticide called Talstar into their pine bark potting material to kill any ants that may be there, Brown said. It takes a few cents’ worth of the chemical to treat each pot, he estimated; a 15-gallon pot includes about 10-cents’ worth. That expense adds up quickly because the nursery churns out hundreds of thousands of plants each year. “It’s a cost of business,” Brown said. Fire ants are at the vanguard of an army of pests expected to trudge northward as fossil fuel emissions continue heat up the planet during this century. A U.S. Department of Agriculture-sponsored study in 2005 predicted that warming temperatures will increase the “habitable area” for red fire ants by 21% by the end of this century, pushing their upper boundary about 80 miles northward. By some time between 2080–89, fire ants could occupy a swath of Virginia as far west as Roanoke and stretching along a line bearing northeast toward the District of Columbia, according to the study. Maryland and Delaware can expect to see their first invasions by that time as well, it says. Fire ants in VA

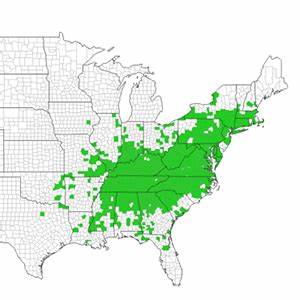

Distribution of Japanese Stilt Grass in the US Distribution of Japanese Stilt Grass in the US Topic suggested by Barry Buschow Alabama Cooperative Extension System describes Japanese stilt grass (Microstegium vimineum) as an aggressive invader of forestlands throughout the eastern United States. Boy is that an understatement! If my small plot of woodlands is any example, stilt grass is a never-ending juggernaut. But as the map below shows, I’m not alone in the Eastern United States in having stilt grass. The plant was accidentally introduced into the Tennessee around 1919 as a result of being used as a packing material in shipments of porcelain from China. Stilt grass is considered one of the most damaging invasive plant species in the United States. It is well adapted to low-light levels. Infestations spread rapidly with flowering and seed production in late summer. The seed can remain viable in the soil for up to five years. Infestations also impact the diversity of native species, reduce wildlife habitat, and disrupt important ecosystem functions. In particular, stilt grass can reduce growth and flowering of native species, suppress native plant communities, alter and suppress insect communities, slow plant succession and alter nutrient cycling. However, it does serve as a host plant for some native satyr butterflies, such as the Carolina Satyr Hermeuptychia sosybius and the endangered Mitchell's Satyr Neonympha mitchellii (Wikipedia). Correct identification is necessary before beginning any management activities. Fortunately, Japanese stilt grass has a unique combination of characteristics that make field identification possible. A field guide published by the Alabama Cooperative Extension System provides simple descriptions and clear pictures of these characteristics along with details on how to distinguish several common look-a-like species. Since Japanese stilt grass is an annual grass, the primary goal is to prevent it from producing seeds. Management techniques include hand pulling, mowing, spraying, burning, goats, and biological control. The New York Botanical Garden's website provides some simple tips on controlling stilt grass. However, choosing the right combination of control methods, applied at the right time, is important so as not to further damage the environment or ecosystem. For instance, the widespread use of herbicides has greatly contributed to wiping out native milkweed plants contibuting to the 80 percent decrease in monarch butterflies in the past 20 years. Everything has trade-offs. Happy pulling! Other References USDA Website |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |