Below are two articles, one from the Washington Post (submitted by Charlene Uhl) and one from the Audubon Society (submitted by Bonnie Beers) that talk about how we can assist insect populations and feed birds properly. Must reads for backyard naturalists! Welcome bugs into your yard When It's Okay (or Not) to Feed Birds

0 Comments

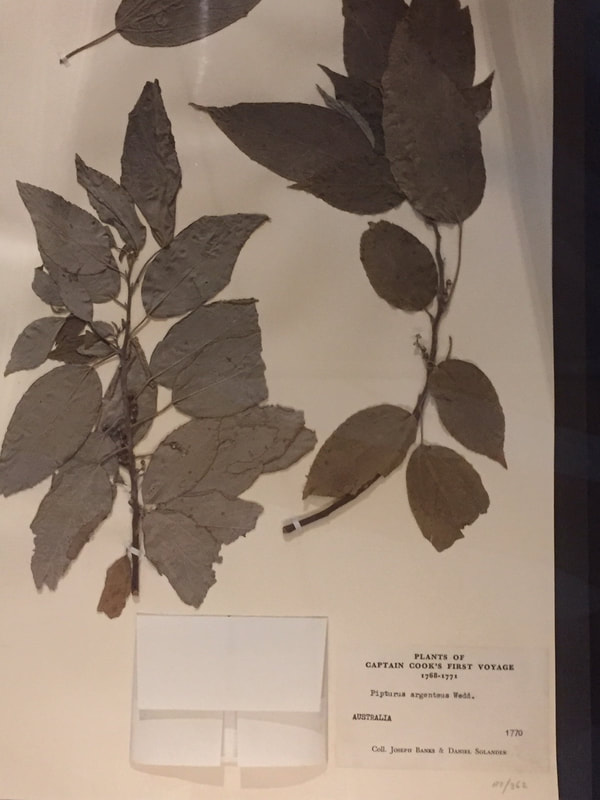

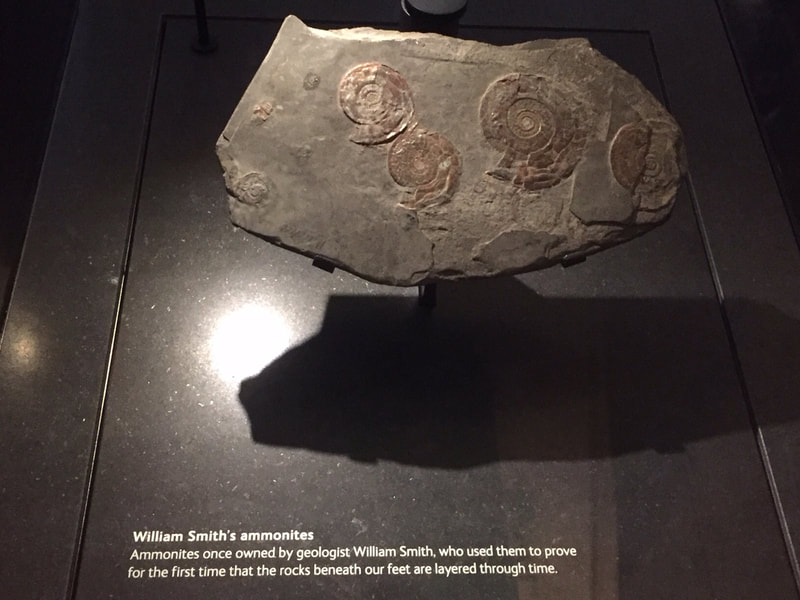

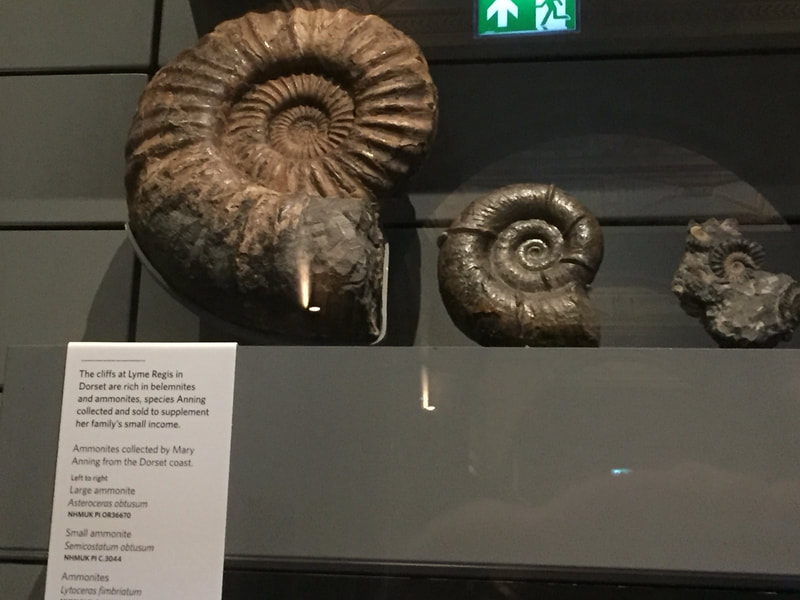

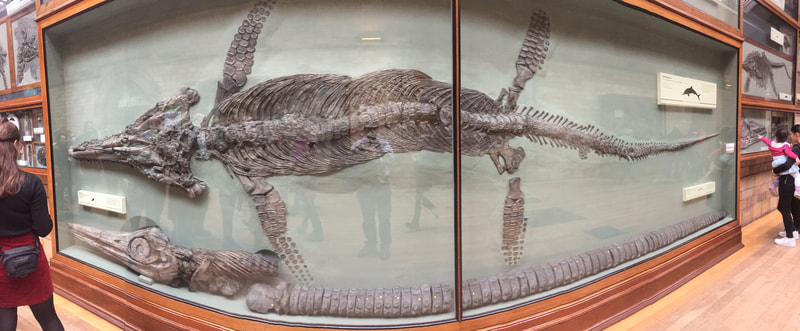

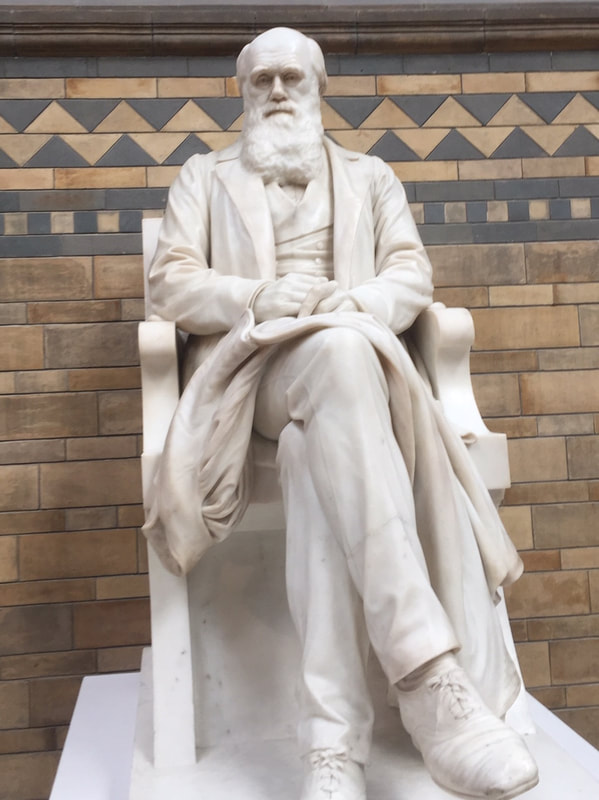

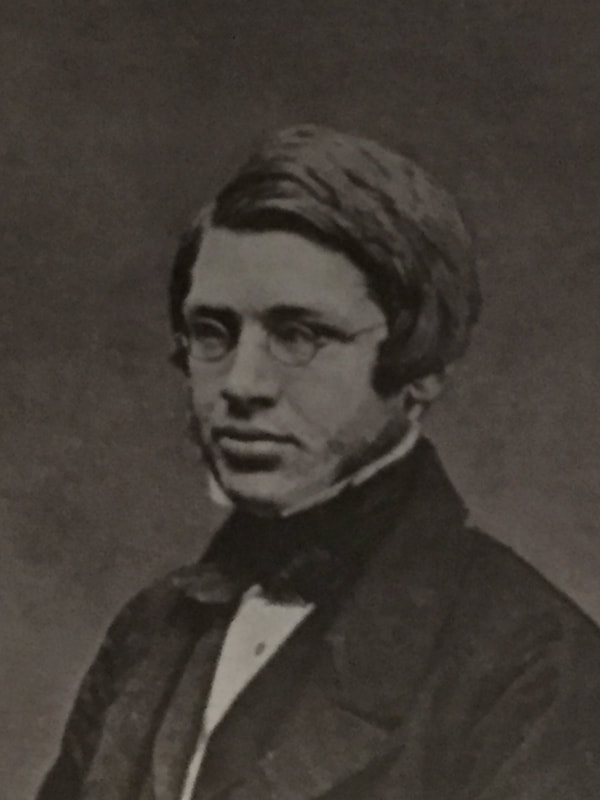

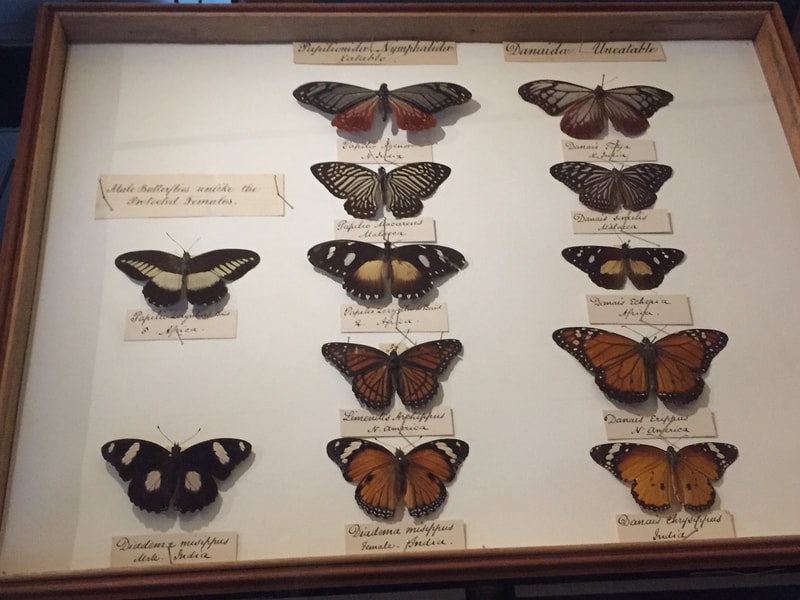

by Jeff Stehm On a trip to London's Natural History Museum this week, I had the opportunity to capture some photos of the early naturalists that lead the way. Joseph Banks (1743 – 1820) was an English naturalist. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage (1768–1771), visiting Brazil, Tahiti, and after 6 months in New Zealand, Australia, returning to immediate fame. Below is a photo I took at the Natural History Museum of one of Joseph Banks' herberium sheets from that voyage with Cook - 350 years old....amazing! He is credited for bringing 30,000 plant specimens home with him; amongst them, he discovered 1,400. He help found and held the position of president of the Royal Society for over 41 years. William 'Strata' Smith (1769–1839) was an English geologist, credited with creating the first detailed, nationwide geological map of any country. At the time his map was first published he was overlooked by the scientific community; his relatively humble education and family connections prevented him from mixing easily in learned society. Financially ruined, Smith spent time in debtors' prison. It was only late in his life that Smith received recognition for his accomplishments, and became known as the "Father of English Geology". A fascinating book about Smith is Simon Winchester's The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology Mary Anning (1799–1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for important finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis in the county of Dorset in Southwest England. Her findings contributed to important changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth. An enjoyable historical fiction book about Mary Anning is Tracy Chevalier's Remarkable Creatures Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882) needs little introduction as a naturalist. His co-discovery of evolution by natural selection with Alfred Russel Wallace (see below) is well-known. Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 – 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator.[1] He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural selection; his paper on the subject was jointly published with some of Charles Darwin's writings in 1858.This prompted Darwin to publish his own ideas in On the Origin of Species. Like Darwin, Wallace did extensive fieldwork; first in the Amazon River basin, and then in the Malay Archipelago, where he identified the faunal divide now termed the Wallace Line, which separates the Indonesian archipelago into two distinct parts: a western portion in which the animals are largely of Asian origin, and an eastern portion where the fauna reflect Australasia. He was considered the 19th century's leading expert on the geographical distribution of animal species and is sometimes called the "father of biogeography".  Science Magazine and the Guardian February 2020 Climate change could increase bumble bees’ extinction risk as temperatures and precipitation begin to exceed species’ historically observed tolerances. A new study adds to a growing body of evidence for alarming, widespread losses of biodiversity and for rates of global change that now exceed the critical limits of ecosystem resilience. Read more about this topic here and here, or read the research study here. Twenty-Year Study Shows How Climate and Habitat Change Impact One Mantid Species By Paige Embry, Entomology Today Ask someone what they know about praying mantids and chances are they’ll bring up the female biting the male’s

head off during mating. It happens, albeit only about 17 percent of the time, but those deaths can be a surprisingly useful tool when studying mantid population changes over time. It’s one of the pieces of information tracked by Lawrence Hurd, Ph.D., a professor of biology at Washington and Lee University, during a 20-year study (1999-2018) of Tenodera aridifolia sinensis, the Chinese praying mantid. The results were published in January in Annals of the Entomological Society of America. In the last few years, studies finding widespread declines in insect abundance have made headlines. Hurd’s long-term study uses one insect in one northern Virginia field to show how such declines can happen. Although the study only followed one species, Hurd and coauthorsnote that the findings should apply to other insects and spiders with a similar life cycle. For this study, Hurd made good use of his resources. He had an insect of unusual size (7-10 centimeters) that beginners (his college ecology lab students) could easily recognize and catch. He also had a nearby field beginning its natural succession, which functioned as a laboratory because the mantids couldn’t easily escape from it. No other suitable fields were close by, and the mantids aren’t very mobile. Five times between 1999 and 2018, on approximately the same day in September, Hurd sent his students across the field in a “skirmish line” to collect, mark, and note every possible T. a. sinensis. Hurd writes in an email, “I always try to base it [the class] on gathering good, usable data instead of just make-work data collection on a question that has already been answered.” To assess the reproductive success of the mantids, they went back after the first frost to collect the oothecae (eggs laid in a gooey substance that hardens into a protective case). They brought the oothecae back to the lab, weighed them, and then returned them to the field. For the oothecae found on the stems of herbaceous plants, that meant “tying [them] on with sewing thread run through the dried foam surrounding the eggs.” Mantids do well in flowery fields with lots of arthropod prey. When succession trends in an area lead to more trees, the population of mantids should shrink. Over the 20 years of this study, two-thirds of the open field area was replaced by trees, and the number of mantids decreased dramatically. However, succession was not the only factor impacting the mantids—climate change was as well. When a Chinese praying mantid lays her eggs, the sex ratio is even. By the time the mantids reach adulthood, males outnumber females. Once mating begins, the percentage of males starts to fall, prey to the females as well as any other predators in the field. Eventually, the females become more common. Even though Hurd and the students sampled on essentially the same calendar day (September 12, 13, or 14) each year, they found that the proportion of males to the total population declined from more than 60 percent in 1999 to about 25 percent in 2018, showing that the mantids were further along in their life cycle. It’s no surprise. For the last 40 years the growing season in northern Virginia has gotten longer and the summers hotter, so the mantids both hatch and reach maturity earlier. This means that some eggs may hatch before frost can put them into diapause, leading to death of the young nymphs and potentially adding to the population losses caused by the successional change. In 2018, Hurd and his students found only three oothecae. In the fall of 2019, he saw no mantids, and found no oothecae after the first frost. This study demonstrates the potential double whammy of habitat loss—even a naturally occurring one—and climate change. Hurd writes, “People are becoming worried about having to include insects in the mass extinction episode that many (including me) feel is already underway.” He says when he talks about this, people often respond with, “‘We gotta worry about bugs, too?'” Unfortunately, as this study illustrates, the answer to that question is “yes.” Find this article in Entomology Today here. Find other articles on declines in insects and biodiversity on the Reading Corner page.  The common eastern firefly, Photinus pyralis, in flight. (Stephen Marshall) The common eastern firefly, Photinus pyralis, in flight. (Stephen Marshall) World’s fireflies threatened by habitat loss and light pollution, experts warn Lightning bugs cannot signal to one another to mate if there’s too much light at night. By Ben Guarino Washington Post Feb. 3, 2020 at 12:22 p.m. EST (shared by Charlene Uhl, Class X) Nearly 2,000 species of fireflies flit, crawl and sparkle across the planet. Some of these lightning bugs are doing fine. Others are not. A survey of 49 of the world’s firefly experts, published Monday in the journal BioScience, has identified the most serious threats to the animals. Habitat loss, in almost all of the regions surveyed, is a problem. Other threats include artificial light, which disturbs their mating rituals; pesticides, which can harm the insects or their invertebrate prey; and water pollution, for species that have an aquatic stage. The report is not a census of the world’s firefly population. But it is “the very first time that we’ve gathered information — this is based on expert opinion — about what the most prominent threats are to the fireflies in different parts of the world,” said study author Sara M. Lewis, a biologist at Tufts University. “For the last decade or more, people have been anecdotally reporting that they’re not seeing fireflies where they used to,” Lewis said. “Good census data over the past few decades” exists for some species, such as Malaysia’s synchronous fireflies and the common European glowworm, Lewis said. “We know that those populations are, in fact, declining.” Elsewhere, however, firefly literature remains “kind of obscure,” she said, and the research community is relatively small. This poll of firefly experts was the “next best thing” to traveling back in time to count firefly populations, said University of Florida entomologist Marc Branham, who was not a member of the research team. He has been told many anecdotes of missing fireflies. And often, he said, they’re believable. Fields once full of flashing insects “are so obvious, in a sort of a sad sense,” when the light vanishes, he said. “One of the things we’ve kind of taken for granted is that fireflies will always be here,” said naturalist Ben Pfeiffer, founder of the nonprofit Firefly Conservation & Research organization and one of the firefly experts who was surveyed. “And we’ve been terribly wrong about that.” In 2018, the International Union for Conservation of Nature created the Firefly Specialist Group, co-chaired by Lewis, to determine whether certain firefly species should be listed as threatened or endangered. “That’s something we’ve never seen happen for a firefly species,” Fitchburg State University biologist Christopher Cratsley said. Cratsley was not a member of the study team. The survey, Lewis said, represents a first step in that process. She cautioned that “we don’t know what the relative importance of these threats to fireflies are. We only know the ranking of what firefly experts believe.” A contrast in firefly health is evident in the eastern United States. There, Photinus pyralis -- also known as the big dipper firefly, for the dipping J-shape path the beetle makes as it flies — remains a common sight at dusk. “It’s a very weedy species. It’s a habitat generalist,” Lewis said. These fireflies swoop over rural meadows and the streetside gardens of the District. “We’re lucky that we have some fireflies that are probably going to be just fine.” Due east of the nation’s capital, however, the situation is dire for the Bethany Beach firefly. That insect, which produces bright green double-flashes, lives only in Delaware’s coastal freshwater wetlands. Residential development has imperiled the species, and in May the Center for Biological Diversity and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation petitioned the Interior Department to add the firefly to the Endangered Species List. Artificial light at night can confuse the fireflies and glowworms that use bioluminescence for mating rituals. In the United Kingdom, female glowworms climb up to perch at the tips of vegetation and glow to attract males. “A number of different studies have shown that artificial light in a glowworm habitat actually prevents the males from finding the females,” Lewis said. Background illumination can also mess up the animals’ sense of timing. “I’ve seen fireflies in New York City that begin courting at like 4 in the afternoon in the summertime, which is not the right time,” Lewis said. In countries such as Japan, Malaysia and the United States — particularly where there are synchronous firefly displays, like the Smoky Mountains — firefly tourism attracts about 200,000 visitors per year, Lewis estimated. Well-meaning tourists may not realize they are endangering the animals they wish to appreciate. “If you have a lot of people who are tromping through the firefly’s habitat, they’re stepping on larvae” or flightless females, she said. Some places have taken precautions against trampling feet and have developed firefly sanctuaries with elevated footpaths. A recently enlarged firefly preserve in New Canaan, Conn., is the first of its kind in North America, Cratsley said, at least as far as he was aware. “The land trust was immediately adjacent to a large mansion — a beautiful home,” he said, of his visit in summer 2019. “But you could go from being surrounded by fireflies to a complete dead zone, of nothing, in that manicured lawn.” The firefly experts encouraged people to join monitoring groups such as Firefly Watch, a citizen-science project run by Mass Audubon that has partnered with Cratsley, Lewis and other researchers. “If people are willing to spend five or 10 minutes each week out in their backyard figuring out what kind of fireflies they have and then counting their flashes,” Lewis said, “we think we could begin to gather the kind of long-term data that we need to figure out what species are in trouble.” Also see: Where Light Pollution Is Seeping Into the Rural Night Sky (click here) |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |