|

Reposted from November, 2020

By Bill Birkhofer Are you seriously considering installing a pollinator garden or meadow in the near future? Well, there’s no better time than this fall and winter to select, prepare and plan your site. Following are some thoughts to help you on your way or reinforce what you’re already doing. Read on - Click Here

0 Comments

By Bonnie Beers

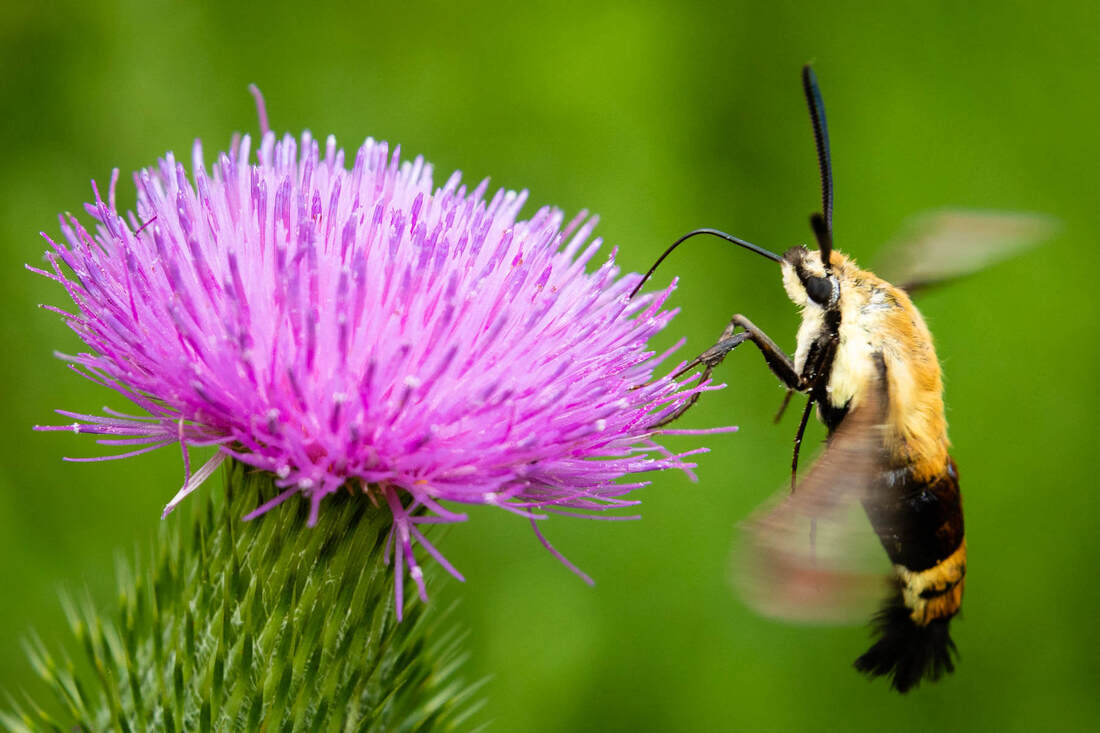

Reposted from November 2020 We wanted to create a low-growth meadow in a 3 acre area near our house. Ever hopeful and loath to use chemical sprays, we decided to give this former hayfield a chance to show its stuff. The site had been mowed for hay with little improvements for decades, at least. It was bordered on one side by a small stream and woods border, on a 2nd side by a deeper wood, and on the remaining sides by our driveway and the mowed/planted areas around our house. Along the woods edges, we found natives like sumac, dogwood, redbud, locust, pine and cedar, and hardwoods. We also found a patch of ailanthus, a good bit of autumn olive and some encroaching vines like Japanese honeysuckle and oriental bittersweet. Read On - Click Here  Trilliums, bloodroot, violets - many wildflowers of spring in eastern North America bloom thanks to ants. The tiny six-legged gardeners have partnered with those plants as well as about 11,000 others to disperse their seeds. The plants, in turn, "pay" for the service by attaching a calorie-laden appendage to each seed, much like fleshy fruits reward birds and mammals that discard seeds or poop them out. But there's more to the ant-seed relationship than that exchange, researchers reported last week at the annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America, which was held online. Read More Here. The fascinating features and critical role of these nocturnal pollinators A freshly emerged cecropia moth dries its wings. A type of silk moth, the cecropia is the largest moth species in North America. (Photo by Mark Beckemeyer/Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0) by Caitlyn Johnstone July 21, 2020 Chesapeake Bay Program submitted by Bonnie Beers Human focus on nature tends to be what we can see and when we can see it during the day. We rightfully champion the busy worker bees, smell the roses and delight in birdsong, yet nature always has new surprises in store. In recent years we’ve begun to discover what happens sight unseen. Flowers fluoresce in brilliant hues beyond the capability of human eyes. Some plants increase the sugar content of their nectar when they detect the vibration of a bee’s wings. And contrary to our assumption that bees and butterflies are the primary players, a lot of pollination happens while we sleep—thanks to moths. Moths as powerhouse pollinators Moths are an evolutionary group that dates back way before the dawn of the bees and butterflies. Because we are more likely to see them during the day, humans are more familiar with butterflies than with moths. However, moths outnumber butterfly species nine to one in discovered Lepidoptera (the insect order that contains moths and butterflies). There are more than 11,000 species of moths in the U.S. alone, and they are a wealth of fascinating facts. In comparison to moths, researcher Jesse Barber of Boise University referred to butterflies as, “an uninteresting diurnal [daytime] group of moths.” A recent study in England found moths are outshining other pollinators, fertilizing more types of plants and flowers that bees overlook. Many bees and butterflies preferentially target flowers rich in nectar. Moths, on the other hand, are generalists, frequenting a wider range of species and visiting those that bees skip. These night shift moths, it turns out, are crucial to pollination. A rosy maple moth is seen in Howard County, Md., on June 12, 2020. (Photo by Emilio Concari/iNaturalist CC BY-NC) Their pollination power is due in part to the tiny scales that give moths their fur-like covering. As the moths visit a diverse array of flowers and enjoy the nectar, their fuzzy bodies collect pollen like a feather duster. While critical to the moths' role in pollination, their fluff actually evolved to confuse the sonar of night-feeding bats. In fact, the evolutionary arms race with bats has been playing out for a long time. Moths can hear, which researchers used to believe developed to help them escape bats and their sonar technology. However, it may be the other way around. Moths and their ears are older, evolutionarily speaking, so it may be that bats evolved their sonar to better capture moths that already have a leg up on detecting a predator’s approach. Fascinating moth features: The proboscis (the tongue) A snowberry clearwing, also known as the hummingbird moth or flying lobster, visits bull thistle growing along the Anacostia River on Kingman Island in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 15, 2019. (Photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program) Moths have an elongated appendage known as a proboscis that can adapt to extract nectar from many types of flowers. These incredible tongues were even written about by Charles Darwin, who marveled at their design and suggested the moths with these proboscises might be the whole reason certain orchids existed. While he was scoffed at for this theory, researchers recently captured footage of a sphinx moth pollinating the beautiful and ethereal ghost orchid using its 30cm proboscis. Moths are so adept with these tongues that they can even drink the tears of sleeping birds without waking them. The antennae The antennae of a male luna moth, pictured, are wider than those of a female because it uses them to seek out the pheromones emitted by the female, which remains stationary until after mating. (Photo by Mike Keeling/Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0) As fabulous as they may appear, the feather-looking antennae of some moths are far from decorative. The detailed structure actually helps the male detect female pheromones from up to several miles away, depending on the species. According to Dr Qike Wang in a recent study, the scales that form the antennae are angled to serve the dual purpose of enhancing female scent and diverting contaminants like dust. The special design creates an area of slow airflow around the antennae, helping the scent to linger and increasing the effectiveness of the pheromones around the sensilla (the sensory receptors). For the lady moth’s part, she is smelling more than the male’s presence. A female moth has the ability to detect reproductive fitness in the male moth’s pheromones. Believe it or not, humans may also have this ability. Moth travel Showy emerald moths are drawn to artificial lights. Green in color as adults, the caterpillar form of this insect resembles a crumpled dead leaf. (Photo by Audrey Hoff/iNaturalist CC BY-NC-ND) “Like a moth to a flame” may be a common phrase, but moths aren’t actually attracted to light itself. When we put lights on our porches and seem to entice moths to it, we’re interfering with the way they orient their world. Moths navigate by the light of the moon, so they keep it at a certain angle to their body. All of the artificial lights we have now are like millions of road signs sending moths in the wrong direction. When they emerge from their cocoons, moths still look like pudgy piglets with fluff and tiny wings. A newly emerged moth will pump fluid, called hemolymph, into its wings to unfurl them to their full adult span. Using their antennae to help balance, strong muscles in their thorax then move the wings up and down and propel them off in search of mates and flowers. Moths of the Chesapeake From the mountains of West Virginia to the lakes of New York and the hills of southern Virginia, the Chesapeake watershed boasts a number of impressive moth species. The most captivating of our region’s moths, at least color-wise, may be the rosy maple moth, Dryocampa rubicunda. This moth has large eyes and is delightfully fluffy, sporting a cotton-candy-lemonade coat of bubblegum pink and bright yellow. As the name suggests, rosy maples gravitate to maple trees. Rosy maple moths are in the silk moth family, Saturniidae, which sports several stunning species that can reach close to the breadth of an adult human’s hand. Silk moths in the Chesapeake are numerous and include such members as the Polyphemus, whose caterpillar eats 86,000 times its body weight, and the woodland-dwelling Prometheus, whose light green caterpillar becomes a black to brown adult moth with a wingspan reaching close to four inches. The spots giant leopard moth, Hypercompe scribonia, shine iridescent blue. (Photo by Greg Lasley/iNaturalist CC BY-NC)

The largest of the silk moths is the Cecropia, which begins its life as a shockingly adorned and bulbous four-inch caterpillar in shades of black to light green with a bluish hue. Once emerging from its cocoon, the cecropia moth unfurls wings of stunning white, orange and grey that reach almost six inches across. The body is equally beautiful, with a fuzzy red face and feet and body bands of crisp black and white. As the sole purpose of the short-lived adult is to mate and reproduce, cecropia do not have a digestive tract. Lunas are one of the most recognizable of the silk moths, eliciting admiring sighs from humans lucky enough to spot their fleeting beauty. Lunas do not have a functioning mouth, living only a few days in their adult form. Their pale green, ethereal wings rightfully distract from the body, though this too is strangely beautiful with its creamy coloring and red wine-hued legs. They have long tails on the ends of their wings, which spin as the moth flies. The fluttering of the tails confuses the sonar of bats and affords these night-flying lovelies some additional protection while finding their mates. Not all moths are nocturnal, and some don’t even look like what we think of as moths. One unusual moth in our watershed is the hummingbird moth, a massive insect many people have seen and mistaken for a bird while watching them visit common garden flowers such as bluebells, bee balm, phlox and verbena. Hummingbird moths like the snowberry clearwing are active during the day, have chunky bodies and even make a humming sound like a hummingbird. If you are interested in seeing these fascinating cross-overs of the animal world, look no further than the leaf piles outside. The loose cocoons of hummingbird moths are often found in leaf litter. Some moth caterpillars in our region look terrifyingly poisonous but aren’t, like the hickory horned devil. Others look incredibly huggable but should not be touched, like the puss caterpillar. In their turquoise coloring and formidable spurs, the harmless hickory horned devil is one of the few moth caterpillars that does not spin a cocoon. Instead, it burrows into the ground to later emerge as the large and aptly named regal moth. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the fluffy exterior of the adorable puss caterpillar conceals venomous spines that can land a full grown human in the hospital with a single touch. Both cute and innocuous, the adult flannel moth appears to be sporting fluffy boots and is completely harmless. This is a southern moth, so it is found in our watershed only in the far-flung reaches of Virginia. Their cocoons are tough, and abandoned ones serve as ready-made homes for a variety of other insects. The list of fascinating local moths goes on. Beautiful wood nymphs mimic bird poop, Scarlet Wings live on lichen, Clymenes are also called “goth moths” and vocalize back to bats. The world of moths is diverse and fascinating, and all moths mentioned can be found in our watershed. Stay up late some night and explore what is out there in the world of darkness. ------------------------------------------ About Caitlyn Johnstone - Caitlyn is the Outreach Coordinator at the Chesapeake Bay Program. She earned her Bachelor's in English and Behavioral Psychology at WVU Eberly Honors College, where she fed her interest in the relationship between human behavior and the natural world. Caitlyn continues that passion on her native Eastern Shore by seeking comprehensive strategies to human and environmental well-being.  Homeowners use up 10 times more pesticide per acre than farmers do. But we can change what we do in our own yards. The eastern swallowtail butterfly that the author’s 91-year-old father-in-law found on the sidewalk. Credit: William DeShazer for The New York Times Homeowners use up 10 times more pesticide per acre than farmers do. But we can change what we do in our own yards. The eastern swallowtail butterfly that the author’s 91-year-old father-in-law found on the sidewalk. Credit: William DeShazer for The New York Times By Margaret Renkl Contributing Opinion Writer, New York Times May 18, 2020, 5:00 a.m. ET NASHVILLE — One day last fall, deep in the middle of a devastating drought, I was walking the dog when a van bearing the logo of a mosquito-control company blew past me and parked in front of a neighbor’s house. The whole vehicle stank of chemicals, even going 40 miles an hour. The man who emerged from the truck donned a massive backpack carrying a tank full of insecticide and proceeded to spray every bush and plant in the yard. Then he got in his truck, drove two doors down, and sprayed that yard, too, before continuing his route all around the block. Here’s the most heartbreaking thing about the whole episode: He was spraying for mosquitoes that didn’t even exist: Last year’s extreme drought ended mosquito-breeding season long before the first freeze. Nevertheless, the mosquito vans arrived every three weeks, right on schedule, drenching the yards with poison for no reason but the schedule itself. And spraying for mosquitoes isn’t the half of it, as any walk through the lawn-care department of a big-box store will attest. People want the outdoors to work like an extension of their homes — fashionable, tidy, predictable. Above all, comfortable. So weedy yards filled with tiny wildflowers get bulldozed end to end and replaced with sod cared for by homeowners spraying from a bottle marked “backyard bug control” or by lawn services that leave behind tiny signs warning, “Lawn care application; keep off the grass.” If only songbirds could read. Most people don’t seem to know that in this context “application” and “control” are simply euphemisms for “poison.” A friend once mentioned to me that she’d love to put up a nest box for bluebirds, and I offered to help her choose a good box and a safe spot for it in her yard, explaining that she would also need to tell her yard service to stop spraying. “I had no idea those guys were spraying,” she said. To enjoy a lush green lawn or to sit on your patio without being eaten alive by mosquitoes doesn’t seem like too much to ask unless you actually know that insecticides designed to kill mosquitoes will also kill every other kind of insect: earthworms and caterpillars, spiders and mites, honeybees and butterflies, native bees and lightning bugs. Unless you actually know that herbicides also kill insects when they ingest the poisoned plants. The global insect die-off is so precipitous that, if the trend continues, there will be no insects left a hundred years from now. That’s a problem for more than the bugs themselves: Insects are responsible for pollinating roughly 75 percent of all flowering plants, including one-third of the human world’s food supply. They form the basis of much of the animal world’s food supply, as well. When we poison the bugs and the weeds, we are also poisoning the turtles and tree frogs, the bats and screech owls, the songbirds and skinks. “If insect species losses cannot be halted, this will have catastrophic consequences for both the planet’s ecosystems and for the survival of mankind,” Francisco Sánchez-Bayo of the University of Sydney, Australia, told The Guardian last year. Lawn chemicals are not, by themselves, the cause of the insect apocalypse, of course. Heat waves can render male insects sterile; loss of habitat can cause precipitous population declines; agricultural pesticides kill land insects and, by way of runoff into the nation’s waterways, aquatic insects, as well. As individuals, we can help to slow such trends, but we don’t have the power to reverse them. Changing the way we think about our own yards is the only thing we have complete control over. And since homeowners use up 10 times more pesticide per acre than farmers do, changing the way we think about our yards can make a huge difference to our fellow creatures. It can make a huge difference to our own health, too: As the Garden Club of America notes in its Great Healthy Yard Project, synthetic pesticides are endocrine disrupters linked to an array of human health problems, including autism, A.D.H.D., diabetes and cancer. So many people have invested so completely in the chemical control of the outdoors that every subdivision in this country might as well be declared a Superfund site. Changing our relationship to our yards is simple: Just don’t spray. Let the tiny wildflowers take root within the grass. Use an oscillating fan to keep the mosquitoes away. Tug the weeds out of the flower bed with your own hands and feel the benefit of a natural antidepressant at the same time. Trust the natural world to perform its own insect control, and watch the songbirds and the tree frogs and the box turtles and the friendly garter snakes return to their homes among us. Because butterflies and bluebirds don’t respect property lines, our best hope is to make this simple change a community effort. For 25 years, my husband and I have been trying to create a wildlife sanctuary of this half-acre lot, planting native flowers for the bees and the butterflies, leaving the garden messy as a safe place for overwintering insects. Despite our best efforts, our yard is being visibly changed anyway. Fewer birds. Fewer insects. Fewer everything. Half an acre, it turns out, is not enough to sustain wildlife unless the other half-acre lots are nature-friendly, too. It’s spring now, and nearly every day I get a flier in the mail advertising a yard service or a mosquito-control company. I will never poison this yard, but I save the fliers anyway, as a reminder of what we’re up against. I keep them next to an eastern swallowtail butterfly that my 91-year-old father-in-law found dead on the sidewalk. He saved it for me because he knows how many flowers I’ve planted over the years to feed the pollinators. I keep that poor dead butterfly, even though it breaks my heart, because I know what it cost my father-in-law to bring it to me. How he had to lock the brakes on his walker, hold onto one of the handles and stoop on arthritic knees to get to the ground. How gently he had to pick up the butterfly to keep from crumbling its wings into powder. How carefully he set it in the basket of the walker to protect it. My father-in-law didn’t know that the time for protection had passed. The butterfly he found is perfect, unbattered by age or struggle. It was healthy and strong until someone sprayed for mosquitoes, or weeds, and killed it, too. By Amanda Heidt

Science, Apr. 8, 2020 , 1:45 PM Monarch butterflies raised in captivity rarely survive the species’ grueling, nearly 5000-kilometer migration. Now, researchers think they know why. When the insects were raised in indoor cages, they grew up paler (an indication of poor health) and 56% weaker (as measured in a grip strength test), researchers report today in Biology Letters. The reason may be that, although most butterflies survive when raised in captivity, only the strongest survive in the wild, The New York Times reports. The researchers don’t discourage hobbyists from raising monarchs, but they say it may not be the best way to restore dwindling populations around the globe. Also See Number of monarch butterflies wintering in Mexico down by more than half By Erin Blakemore

Washington Post March 14, 2020 at 8:00 a.m. EDT Bee hotels — boxes promoted as good nesting places. “Bee-friendly” farming techniques behind favorite foods. Are the claims true — or just honey-drenched hype? Lila Westreich, a bee researcher at the University of Washington, says companies take advantage of well-intentioned consumers by “bee-washing.” The term, first coined by researchers in 2015, refers to greenwashing, in this case a marketing strategy that makes a product or practice seem beneficial to threatened bees. (Greenwashing evolved from the term whitewashing and means an environmental spin.) In The Conversation, Westreich writes that the practice can actually hurt bees. Bee hotels are advertised as safe nests for bees, for example, but some may be dangerous. The welfare of honeybees may be overemphasized, misleading the public about environmental priorities. Wild native bees are at particular risk. Of the 20,000 or so bee species in the world, only about 4,000 are native to North America — the bumblebee among them. These bees don’t produce honey, and they’re less sociable and well-known than their so-sweet counterparts. The majority of American bees don’t produce honey. Honey bees came to the United States from Europe. Kelsey K. Graham, another bee researcher, calls them the “chickens of the bee world” because they are so domesticated. Unlike hive-dwelling honeybees, which are carefully bred, imported to the country for use in crop pollination and managed, the majority of native bees are solitary and nest underground. They reportedly pollinate up to 80 percent of plants, including many crops. They’re also at risk: In a 2017 study, the Center for Biological Diversity found that more than 50 percent of North American native bee species are declining; 24 percent are threatened with extinction. Native bees are threatened by climate change, habitat depletion and pesticide use — but honey bees get most of the publicity. “While many people are worried about honey bees, it’s also important to understand the jeopardy that native bees face,” Westreich writes. “Companies and organizations use bee-washing to boost their image, taking advantage of the public’s lack of knowledge of native bees.” By bragging about how they help honey bees, notes Westreich, they play down the importance of native species that, unlike honey bees, are actually endangered. They also play up their solutions, such as bee hotels, that can hurt bees by spreading disease. Ready to inoculate yourself against misleading claims about bees? Read Westreich’s article at bit.ly/beewashing  Science Magazine and the Guardian February 2020 Climate change could increase bumble bees’ extinction risk as temperatures and precipitation begin to exceed species’ historically observed tolerances. A new study adds to a growing body of evidence for alarming, widespread losses of biodiversity and for rates of global change that now exceed the critical limits of ecosystem resilience. Read more about this topic here and here, or read the research study here.  Submitted by Barry Buschow Commercial pumpkin growers routinely rent honey bees so they have enough insects to pollinate their crops, but a new study published in the Journal of Economic Entomology suggests that wild bees can do the job for free. The three-year study found that wild bumble bees and squash bees could easily handle the pollination required to produce a full yield of pumpkins in all of the tested commercial fields, according to Carley McGrady, the lead author of the study. The pumpkin study was part of a broader initiative, called the Integrated Crop Pollination Project, or Project ICP (http://icpbees.org/), which was headquartered at Michigan State University and funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative. To read more, click here.

|

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |