|

Tis the Season for Turtles: Maryland turtles are out and about in summer's warm weather.

Published July 28, 2020 in Conservation A turtle isn't Maryland's state reptile for nothing. Eighteen turtle species can be found throughout the state and in state waters—in ponds and bogs, streams and rivers, woodlands and wetlands—from the mountains of Garrett County to the waters of Worcester County and everywhere in between. With so many turtles making their way (slowly) around, it's not uncommon for Marylanders to encounter them in the wild, particularly in summer when the weather is warm. If you see one, what should you do? The general rule—as with all wildlife—is to keep a respectful distance and look but don't touch. You can disrupt a turtle's activity by touching or moving it. For example, aquatic species encountered on land are most likely females looking for a suitable spot to dig a nest and lay eggs. Females strive to find the perfect location where predators can't find their eggs and where their hatchlings can find their way back to water. Handling them during this vulnerable time would be very disruptive. Eastern Box Turtle With their dark shells covered in yellow-orange spots, Eastern box turtles are one of the most encountered species in Maryland, often found while hiking through forests. Unfortunately, many box turtle populations are now in decline due to habitat loss from development and road mortalities. This woodland species is terrestrial, spending most of their time on land, in sunny open spaces as well as shady hiding places. They have a strong homing sense and are known to live out their lives in an area about the size of a football field, which is why they should never be picked up and moved. An exception is if you find a box turtle in a place where it's not safe, like trying to cross a road. Each year, countless turtles are killed by cars. Among the tips the Mid-Atlantic Turtle and Tortoise Society offers for helping a turtle cross a road is to move it the shortest distance possible in the same direction it was heading, at least 30 feet from the road. Follow MATTS' recommendations for safely handling turtles, using two hands to hold both sides of the shell and lifting gently. A thorny briar patch or carpet of fallen leaves gives the turtle places to hide from predators. Red-Eared Slider From March to September, these turtles with bright red stripes on the side of their heads can be spied swimming and basking in the Inner Harbor, Lake Montebello and Lake Roland, among other spots in Baltimore City and most Maryland counties. They prefer freshwater habitats but can tolerate low-salinity, brackish water, and favor the still water of ponds, lakes, reservoirs and slow moving sections of rivers to fast moving streams. These turtles are an invasive species, native to the mid- and south-central United States. Thanks to the pet trade, the red-eared slider is now the world's most widespread freshwater turtle. Hatchlings the size of a quarter can grow bigger than a dinner plate and live for 30 years, so irresponsible pet owners choose to release the turtles rather than continue to care for them. Red-eared sliders with shells bigger than 4 inches can still be sold in Maryland pet shops, but it's illegal to sell hatchlings. If you see red-eared slider turtle hatchlings for sale in Maryland, it's best to report it to the Natural Resources Police at 410-356-7060. And if you have a pet turtle of any kind that you can no longer keep, do the right thing; don't release it into the wild. A close relative of the red-eared slider, the yellow-bellied slider, is now being observed with increased frequency around Maryland. Yellow-bellied sliders are native to the southeastern U.S. and, like the red-eared slider, are most likely now being seen in Maryland because people have released unwanted pets into the wild. Snapping Turtle Snapping turtles are another common species found throughout Maryland, in or very near fresh or slightly brackish water. They can grow quite large—with a shell length ranging from 8 to 14 inches—and their bites pack a punch. Because their necks are long and flexible enough for their powerful jaws to reach most parts of their body, it's not a good idea to touch one or pick it up. Female snapping turtles sometimes lay their eggs a fair distance from the water they emerged from, so you can sometimes find hatchlings far from water, trying to make their way to it. It's important to leave the hatchling outdoors, but if you feel it's in danger, you can carefully move it closer to the water's edge where there is plenty of mud and places to take cover. Diamondback Terrapin The diamondback terrapin is Maryland's official state reptile and has been affiliated with the University of Maryland College Park since 1933. Terps officially became the school's mascot in 1994. To protect diamondback terrapins in Maryland, a 2007 state law (which the National Aquarium helped pass) bans removing them from the wild for commercial purposes. Young terrapins are vulnerable to predators on land, in water and from the sky, including birds, raccoons, opossums and foxes. They prefer brackish water and spend their early years hiding in marsh grass habitat that gets flooded by high tides twice a day. If you find a terrapin out of habitat, it's best to release it in the nearest marsh grass habitat during a high tide. Share What You See If you happen to see a turtle or other reptile in the wild, whether during the City Nature Challenge or not, consider uploading a photo and information to iNaturalist to share your find with others!

0 Comments

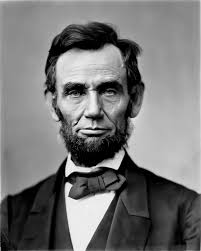

Dr. Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. Credit: Mary Lewandowski, National Park Service. Dr. Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. Credit: Mary Lewandowski, National Park Service. by Delia O'Hara AAAS Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Program Manager of the Migratory Connectivity Project (MCP) at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center at the National Zoo, learned to love animal migrations as an undergraduate student at Virginia Tech, watching wildebeest pound across the Serengeti in Africa in their annual search for greener grass. Now, Harrison coordinates the MCP's ambitious efforts to discover a fuller picture of the lives of birds: Where do birds like the long-billed curlew or the broad-winged hawk, spend their winters? Where do birds we see in other seasons go to breed? These questions are of an urgent nature as bird populations are facing steady declines around the world. Last fall, an alarming study showed that North America has lost three billion birds since 1970, about one-third of the total bird population. For Harrison, however, the study created new resolve around learning all we can about birds in hopes of saving them. “Without that knowledge of where they go, we can't even begin to figure out where the impacts are” — or how to structure conservation efforts, says Harrison, an ecologist and conservation biologist. The question of why some birds disappear for several months has intrigued humans for millennia. Europeans theorized that birds hibernated in rivers to survive winters, like frogs; or turned into other birds; or flew to the moon. Then, in 1822, a hunter shot a stork in northern Germany and discovered an African arrow embedded in its body. But the mysteries of the 40% of bird species that migrate are only now beginning to be unraveled. Electronic tracking, such as small devices that are attached to birds, and other technologies, have played a large role in this, Harrison says. Early trackers used in the 1990s were so big that only large birds like albatross and eagles could fly with them, she says. Now, tiny GPS devices with solar-powered batteries are being fitted to much smaller birds. The MCP has field projects all over the Americas to track migrating birds, working with graduate students and agency biologists, choosing species that little is known about, or that have markedly declining numbers — the common nighthawk, rusty blackbird and Connecticut warbler, to name a few. Harrison herself leads projects involving oceanic and coastal birds, often in Arctic North America, a natural fit for a biologist with a background in marine animals. One bird Harrison studies, the Arctic tern, travels from the northern tip of the world every year, to the southern tip, and back, which can be an annual journey of more than 44,000 miles, Harrison says. Earlier in her career, Harrison studied the migrations of large oceanic predators like seals, sharks and leatherback turtles as part of the Tagging of Pelagic Predators project. In one study of 14 such species, her team looked at their relationship with the human societies they pass, and the various levels of protection they are afforded as they travel. She presented that study’s findings to participants of the United Nations First Intergovernmental Conference on Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, in hopes of bolstering the chances of a treaty, still under consideration, to make migrating sea animals' journeys safer. Harrison travels extensively for her research, and she will go back to that once the pandemic eases. This summer, though, there is a moratorium on travel. So instead, “We have been able to take a breather, revisit the data we have collected, and tell some of the interesting stories,” she says. One such story includes the first full-year tracking, held through 2019-2020, of the Pomarine Jaeger, a “gnarly” predatory seabird that breeds in the Arctic. “We discovered that three closely related species of Jaegers nesting on the same island in the Arctic dispersed during migration to four different oceans to spend the rest of their year,” she says. “That's amazing to me.” Harrison has also enjoyed returning to live near the Chesapeake Bay to work at the Smithsonian. She grew up on the bay, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where her father's family settled in the 17th century and became “watermen”— solely oystermen until the collapse of the oyster population forced them to diversify into harvesting eels, crabs and other food animals in the bay. Harrison's parents were a math teacher and office manager of an electrical contracting company, but she spent time at her grandmother's house on Tilghman Island, “poking around in the marsh.” She knew early on she would be a biologist, but thought she would be an estuarine researcher, studying Chesapeake Bay. And lately, Harrison has indeed had a chance to study brown pelicans in the bay with Dave Brinker of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, who discovered their first nest found in Maryland, in 1987. Harrison's father came with her as a field volunteer on one trip, and it was “very special to have him involved,” she says. “I respect scientific knowledge so much,” she says. “But I got a different kind of education from people who got up at 4 am to go out to catch crabs. They know the bay, they know the animals, they know these systems. That's knowledge to respect, too.”  Earyn McGee in the field. Earyn McGee in the field. 7/29/2020 by Marsha Walton AAAS Herpetologist and University of Arizona Ph.D. candidate Earyn McGee’s research has her well prepared for obstacles like oppressive heat, treacherous terrain and even venomous animals. Her field research takes her to the Chiricahua Mountains of southern Arizona, where she’s determining the effects of stream drying on lizard communities for her doctorate research in conservation biology. This enables McGee a closeup look in studying lizards and their diet, and how the climate crisis may be altering it. She and the undergraduates she works with must first deftly catch the reptiles, weigh and measure them, then document their sex and overall health. It is demanding and unpredictable work. And it has sometimes been made riskier by unsettling encounters with police, whose actions imply that, as a young scientist of color, she does not have a right to conduct her field studies. “Where I work is pretty remote,” says McGee. “A lot of the time, it's Border Patrol, or some form of law enforcement stopping us [from working]. Last year, we had these military guys follow us into our site. A couple of days prior, we were out in the group with a whole lot of white people, we didn't have that same type of surveillance in the same exact spot,” says Already well known as a science communicator on social media, McGee counters such racist incidents with the message that the natural world belongs to everyone to love and to protect. And she stresses that excitement for nature can come at any point in time, whether hiking through a National Park or looking up at a tree in New York City. Her courage in speaking out went viral shortly after a white woman made racist threats against Black birdwatcher Christian Cooper in Central Park on May 25, 2020. McGee and several colleagues, who had already been communicating about academic and diversity issues, sprang into action. They created #BlackBirdersWeek. Photos and experiences soon flooded social media from all over the world. In interviews and podcasts during the week (May 31-June 5), scientists and naturalists shared examples of Black people, from birders to hikers to photographers, enjoying nature and outdoor spaces. The Central Park incident of racism, and the Twitter and Instagram responses to it, became another visible, widely shared facet in what’s become known as the U.S. Civil Rights racial injustice reckoning of 2020. Besides her activism aimed at adults, McGee also shares her knowledge about wildlife conservation with a younger audience. Lizards may be small, she says, but they can also be very swift and very clever. “[Catching] them the first time, depending on the lizard, can be relatively easy. But that next time when they see you coming, they're like, ‘Oh no, not this again,’ and they take off running,” she says. And she has some stories of these types of experiences she often shares on her social media accounts. “So I'm running after this lizard, sprinting. This lizard is really putting up a good chase. I'm hopping over logs and rocks and stuff. I caught her, but before I did, I took a picture and I told people on Twitter the story of what happened,” says McGee. Her followers were intrigued by the elusive lizard story. Since June 2018, thousands of curious students and adults regularly scour the photos on her informal Twitter quiz, using the hashtag, #FindThatLizard. After locating the reptiles, McGee then shares details about their camouflage, eating habits and survival skills. She’s heard from many science teachers who now start their classes off with this quest. McGee says lizards are an easy sell to get kids hooked on science. In her outreach work, she shares fun facts about lizards, such as some lay eggs, some give live birth, others can even clone themselves. And what’s not to love about a Gila monster, asks McGee? “People pay money to come from all around the world for the hope of seeing this lizard (the Gila monster). It's one of few venomous lizards in the world, and compounds from its saliva have been used to create medical treatments for diabetes. So, lizards are cool,” she says. McGee’s activism and fearlessness led to her recognition as one of the younger AAAS IF/THEN® Ambassadors. In her role as an ambassador, McGee shares with young girls her expertise on the power of social media for women and underserved minorities in STEM fields. She also hopes to introduce young girls to career paths in natural resources. Still, McGee knows other types of outreach are needed to improve diversity and equity in STEM. While she says there is currently a lot of activism on her own campus to combat racism and xenophobia, McGee says institutions need to do more to assist Indigenous Mexican-American and undocumented students. When her studies are complete in about a year, McGee plans a career as a science communicator, perhaps hosting a nature show on TV. And her quest for social justice will stay closely tied to her career path. “I really want to be able to create pathways for Black, Indigenous, other people of color to enter into natural resources fields, and even if they don't want to do it as a job, maybe find it as a new hobby. So that's really what I hope to accomplish in the future,” said McGee. By Meagan Cantwell Jul. 27, 2020 , 9:00 AM Science To save energy, many insects swivel their head—instead of their entire body—to scan the world around them. Researchers have now replicated this with a tiny camera with a one-of-a-kind arm they can maneuver from a smartphone. The total system weighs just 248 milligrams—less than a dollar bill. When strapped onto a beetle’s back, the camera can stream video in close to real time. It can also pivot to provide a panoramic view from the beetle’s perspective (as seen in this video). What’s more, when the camera was mounted onto an insect-size robot, the bot used up to 84 times less energy by moving the arm of the camera instead of its entire body. The technology is one of the smallest, self-powering vision systems to date, researchers report this month in Science Robotics. In the future, scientists could use these tiny cams to gain insight into the habits of insects outside the lab. The fascinating features and critical role of these nocturnal pollinators A freshly emerged cecropia moth dries its wings. A type of silk moth, the cecropia is the largest moth species in North America. (Photo by Mark Beckemeyer/Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0) by Caitlyn Johnstone July 21, 2020 Chesapeake Bay Program submitted by Bonnie Beers Human focus on nature tends to be what we can see and when we can see it during the day. We rightfully champion the busy worker bees, smell the roses and delight in birdsong, yet nature always has new surprises in store. In recent years we’ve begun to discover what happens sight unseen. Flowers fluoresce in brilliant hues beyond the capability of human eyes. Some plants increase the sugar content of their nectar when they detect the vibration of a bee’s wings. And contrary to our assumption that bees and butterflies are the primary players, a lot of pollination happens while we sleep—thanks to moths. Moths as powerhouse pollinators Moths are an evolutionary group that dates back way before the dawn of the bees and butterflies. Because we are more likely to see them during the day, humans are more familiar with butterflies than with moths. However, moths outnumber butterfly species nine to one in discovered Lepidoptera (the insect order that contains moths and butterflies). There are more than 11,000 species of moths in the U.S. alone, and they are a wealth of fascinating facts. In comparison to moths, researcher Jesse Barber of Boise University referred to butterflies as, “an uninteresting diurnal [daytime] group of moths.” A recent study in England found moths are outshining other pollinators, fertilizing more types of plants and flowers that bees overlook. Many bees and butterflies preferentially target flowers rich in nectar. Moths, on the other hand, are generalists, frequenting a wider range of species and visiting those that bees skip. These night shift moths, it turns out, are crucial to pollination. A rosy maple moth is seen in Howard County, Md., on June 12, 2020. (Photo by Emilio Concari/iNaturalist CC BY-NC) Their pollination power is due in part to the tiny scales that give moths their fur-like covering. As the moths visit a diverse array of flowers and enjoy the nectar, their fuzzy bodies collect pollen like a feather duster. While critical to the moths' role in pollination, their fluff actually evolved to confuse the sonar of night-feeding bats. In fact, the evolutionary arms race with bats has been playing out for a long time. Moths can hear, which researchers used to believe developed to help them escape bats and their sonar technology. However, it may be the other way around. Moths and their ears are older, evolutionarily speaking, so it may be that bats evolved their sonar to better capture moths that already have a leg up on detecting a predator’s approach. Fascinating moth features: The proboscis (the tongue) A snowberry clearwing, also known as the hummingbird moth or flying lobster, visits bull thistle growing along the Anacostia River on Kingman Island in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 15, 2019. (Photo by Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program) Moths have an elongated appendage known as a proboscis that can adapt to extract nectar from many types of flowers. These incredible tongues were even written about by Charles Darwin, who marveled at their design and suggested the moths with these proboscises might be the whole reason certain orchids existed. While he was scoffed at for this theory, researchers recently captured footage of a sphinx moth pollinating the beautiful and ethereal ghost orchid using its 30cm proboscis. Moths are so adept with these tongues that they can even drink the tears of sleeping birds without waking them. The antennae The antennae of a male luna moth, pictured, are wider than those of a female because it uses them to seek out the pheromones emitted by the female, which remains stationary until after mating. (Photo by Mike Keeling/Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0) As fabulous as they may appear, the feather-looking antennae of some moths are far from decorative. The detailed structure actually helps the male detect female pheromones from up to several miles away, depending on the species. According to Dr Qike Wang in a recent study, the scales that form the antennae are angled to serve the dual purpose of enhancing female scent and diverting contaminants like dust. The special design creates an area of slow airflow around the antennae, helping the scent to linger and increasing the effectiveness of the pheromones around the sensilla (the sensory receptors). For the lady moth’s part, she is smelling more than the male’s presence. A female moth has the ability to detect reproductive fitness in the male moth’s pheromones. Believe it or not, humans may also have this ability. Moth travel Showy emerald moths are drawn to artificial lights. Green in color as adults, the caterpillar form of this insect resembles a crumpled dead leaf. (Photo by Audrey Hoff/iNaturalist CC BY-NC-ND) “Like a moth to a flame” may be a common phrase, but moths aren’t actually attracted to light itself. When we put lights on our porches and seem to entice moths to it, we’re interfering with the way they orient their world. Moths navigate by the light of the moon, so they keep it at a certain angle to their body. All of the artificial lights we have now are like millions of road signs sending moths in the wrong direction. When they emerge from their cocoons, moths still look like pudgy piglets with fluff and tiny wings. A newly emerged moth will pump fluid, called hemolymph, into its wings to unfurl them to their full adult span. Using their antennae to help balance, strong muscles in their thorax then move the wings up and down and propel them off in search of mates and flowers. Moths of the Chesapeake From the mountains of West Virginia to the lakes of New York and the hills of southern Virginia, the Chesapeake watershed boasts a number of impressive moth species. The most captivating of our region’s moths, at least color-wise, may be the rosy maple moth, Dryocampa rubicunda. This moth has large eyes and is delightfully fluffy, sporting a cotton-candy-lemonade coat of bubblegum pink and bright yellow. As the name suggests, rosy maples gravitate to maple trees. Rosy maple moths are in the silk moth family, Saturniidae, which sports several stunning species that can reach close to the breadth of an adult human’s hand. Silk moths in the Chesapeake are numerous and include such members as the Polyphemus, whose caterpillar eats 86,000 times its body weight, and the woodland-dwelling Prometheus, whose light green caterpillar becomes a black to brown adult moth with a wingspan reaching close to four inches. The spots giant leopard moth, Hypercompe scribonia, shine iridescent blue. (Photo by Greg Lasley/iNaturalist CC BY-NC)

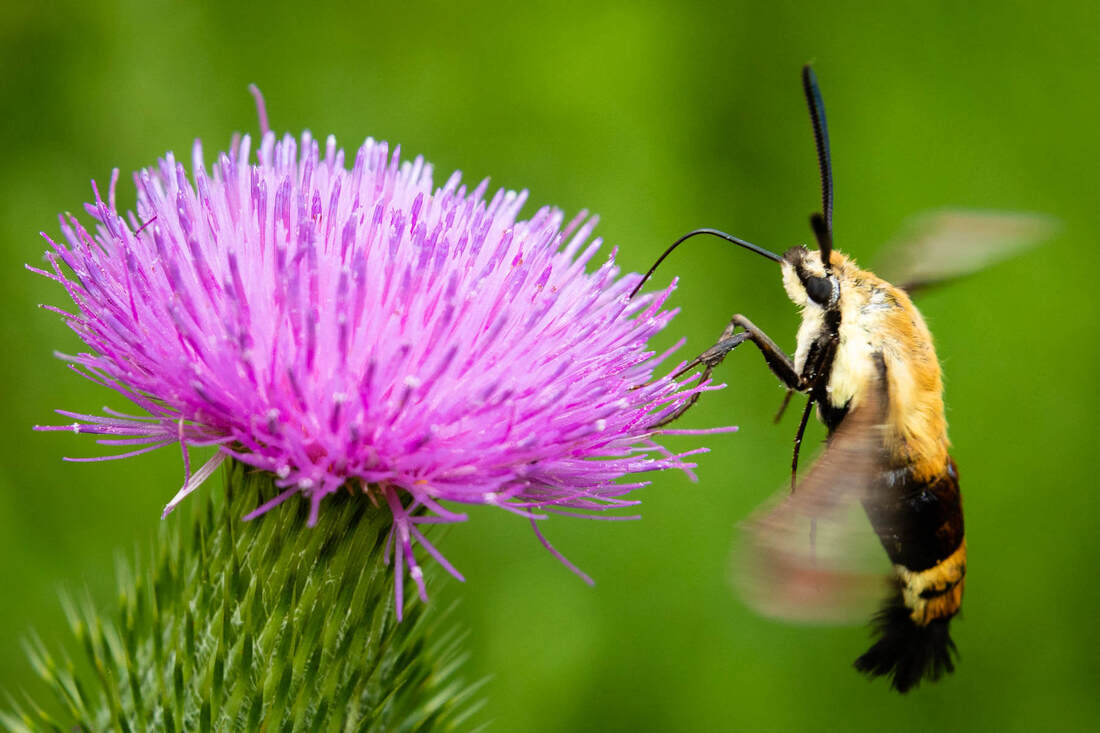

The largest of the silk moths is the Cecropia, which begins its life as a shockingly adorned and bulbous four-inch caterpillar in shades of black to light green with a bluish hue. Once emerging from its cocoon, the cecropia moth unfurls wings of stunning white, orange and grey that reach almost six inches across. The body is equally beautiful, with a fuzzy red face and feet and body bands of crisp black and white. As the sole purpose of the short-lived adult is to mate and reproduce, cecropia do not have a digestive tract. Lunas are one of the most recognizable of the silk moths, eliciting admiring sighs from humans lucky enough to spot their fleeting beauty. Lunas do not have a functioning mouth, living only a few days in their adult form. Their pale green, ethereal wings rightfully distract from the body, though this too is strangely beautiful with its creamy coloring and red wine-hued legs. They have long tails on the ends of their wings, which spin as the moth flies. The fluttering of the tails confuses the sonar of bats and affords these night-flying lovelies some additional protection while finding their mates. Not all moths are nocturnal, and some don’t even look like what we think of as moths. One unusual moth in our watershed is the hummingbird moth, a massive insect many people have seen and mistaken for a bird while watching them visit common garden flowers such as bluebells, bee balm, phlox and verbena. Hummingbird moths like the snowberry clearwing are active during the day, have chunky bodies and even make a humming sound like a hummingbird. If you are interested in seeing these fascinating cross-overs of the animal world, look no further than the leaf piles outside. The loose cocoons of hummingbird moths are often found in leaf litter. Some moth caterpillars in our region look terrifyingly poisonous but aren’t, like the hickory horned devil. Others look incredibly huggable but should not be touched, like the puss caterpillar. In their turquoise coloring and formidable spurs, the harmless hickory horned devil is one of the few moth caterpillars that does not spin a cocoon. Instead, it burrows into the ground to later emerge as the large and aptly named regal moth. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the fluffy exterior of the adorable puss caterpillar conceals venomous spines that can land a full grown human in the hospital with a single touch. Both cute and innocuous, the adult flannel moth appears to be sporting fluffy boots and is completely harmless. This is a southern moth, so it is found in our watershed only in the far-flung reaches of Virginia. Their cocoons are tough, and abandoned ones serve as ready-made homes for a variety of other insects. The list of fascinating local moths goes on. Beautiful wood nymphs mimic bird poop, Scarlet Wings live on lichen, Clymenes are also called “goth moths” and vocalize back to bats. The world of moths is diverse and fascinating, and all moths mentioned can be found in our watershed. Stay up late some night and explore what is out there in the world of darkness. ------------------------------------------ About Caitlyn Johnstone - Caitlyn is the Outreach Coordinator at the Chesapeake Bay Program. She earned her Bachelor's in English and Behavioral Psychology at WVU Eberly Honors College, where she fed her interest in the relationship between human behavior and the natural world. Caitlyn continues that passion on her native Eastern Shore by seeking comprehensive strategies to human and environmental well-being. Find out by reading this Scientific American article sent in by Bob Powers, Class X

Photo: Radim Schreiber Night falls in the cove where I’ve set up a camera and tripod, one of those places where the sun sets early thanks to steep terrain and thick tree cover overhead. But the darkness doesn’t last. Not long after twilight, the entire forest is pulsing with hundreds of perfectly-timed, golden pinpoints of light. I reach for my camera and start recording video. The lights are from Photinus carolinus, the famed synchronous fireflies that display each year in and around the Elkmont section of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The fireflies are a biological oddity and visual wonder, with males flashing in unison—a behavior that attracts females—for several weeks each summer. While fireflies are a common occurrence here in the East, this particular species is our only true synchronous flashing insect. Its display in Elkmont attracts thousands of people each year. However, I’m sitting alone in that cove. Elkmont and its crowds are hours away. Instead, I’ve traveled well beyond the national park as a researcher chasing reports of the same species. Synchronous fireflies are known from only a handful of places outside of Elkmont, and if the light show that members of the public have been seeing here is the same one found in the Smokies, we’ll be able to add another population to that list. Counting the insects’ flash pattern carefully, my excitement builds: we’ve located another spot. Here in the Blue Ridge, though, discovery isn’t always a good thing. In fact, our fireflies have become an emblem of the challenges facing resource managers as public interest in the outdoors grows at an explosive rate. Wildlife is a big part of that draw, and in a world accelerated by social media, natural wonder travels fast. A 2017 video of the Elkmont fireflies shared by the Knoxville News Sentinel racked up nearly 60,000 views on Facebook alone. That attention can be a double-edged sword. For many, experiencing something as spectacular as a firefly display can ignite a lifetime of learning about the outdoors. But our mountains’ species are often fragile, and too many people striking out to find them can spell bad news. The overwhelming popularity of Elkmont’s display has led to a lottery being used to control the number of visitors hoping to catch the show. In North Carolina’s DuPont State Forest, concern about visitor impacts on another popular firefly species has led to seasonal trail closures. This conundrum has also touched off a national conversation about the tradeoffs of what we share—and how we share it—related to the outdoors. Some websites are now scrubbing GPS coordinates from wildlife photos out of fear that they might provide a road map for poachers hunting rare species. And a growing group is lobbying for an “eighth principle” related to media and tourism promotion to join the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics’ existing guidelines for low-impact outdoor use. Part of the problem is that buzz about an outdoor activity or destination can spread faster than management plans can keep up. In the West, Instagram posts have transformed little-known alpine lakes into viral outdoor meccas, sending hordes of people flocking to sensitive locations that can be damaged by overcrowding. A video shared by a regional tourism page flashed across my own feed earlier this year, showing folks blasting a caravan of ATVs up the middle of a creek—a practice that can kill aquatic life and pollute water for users downstream. For the Blue Ridge’s fireflies, the challenges are more subtle. Females need to be able to see the males’ light show to choose a mate, and too many people walking around with flashlights and smartphones can outshine their glow. Even in total darkness, excess foot travel can compact the spongy leaf litter and soil needed for young fireflies to develop. The more people who come looking for the fireflies without knowing how to minimize their impact, the less chance there is that anything will be left for them to see. So how can we walk that line between sharing outdoor experiences and causing unintended harm? The Leave No Trace Center’s recommendations coalesce around a simple idea: stop and think. “If we can simply encourage people to stop and think about the potential impacts and associated consequences of their actions,” the Center writes in a blog post on the issue, “we can go a long way towards ensuring the protection of our shared recreational resources.” The Center’s strategy might mean considering what information should accompany a photo or video before posting it, or maybe it could mean waiting to promote a spot that isn’t ready for the spotlight. For tourism officials, a conversation with land managers prior to marketing an asset could help prevent negative outcomes. Those considerations are on my mind as I watch that newly-discovered population of fireflies. Promoting them could be a release valve of sorts, taking pressure off of crowded firefly-watching spots like Elkmont. But could too much promotion hurt the fireflies before experts can understand how much attention they can handle? I’m mulling over that question as a car pulls into a nearby parking lot, headlights sweeping across the forest floor. The insects’ light show stops, and a family jumps out. “Where are the fireflies?” they yell. The secret has already gotten out. Before I have a chance to reply, the group runs off through the night, spotlights in hand, deeper into an emptier woods. BY WALLY SMITH Blue Ridge Outdoors 24 JUN 18  By Lauren Harper, guest blogger for State of the Planet, Earth Institute, Columbia University Every autumn, as winter winds begin to blow and rain colorful leaves from the trees, you may notice the dierences in each leaf’s color and shape. This is a form of biodiversity, or the variety of living organisms on earth. Biodiversity can be seen within species, between species, and within and between ecosystems. Although biodiversity is hard to measure on a global scale, in recent years there has been scientic consensus that the planet’s biodiversity is in decline. That’s not great news, because in general, the more species that live in an area, the healthier that ecosystem is—and the better off we humans are. Why Biodiversity Matters Healthy ecosystems require a vast assortment of plant and animal life, from soil microbes to top level predators like bears and wolves. If one or more species is removed from this environment, no longer serving its niche, it can harm the ecosystem. Introducing foreign or invasive species into a habitat can have similar results, as the invasive species can out-compete the native species for food or territory. Biodiversity affects our food, medicine, and environmental well-being. Dragonflies, ladybugs and beetles pollinate many of the crops we rely on for food, as well as plants in natural ecosystems. One type of pollinator cannot do it all, hence the importance of biodiversity. Loss of habitat—for example, when humans convert meadows into parking lots or backyards—is reducing pollinator populations. If pollinators were to disappear entirely, we would lose over one-third of all crop production. This would reduce or eliminate the availability of foods like honey, chocolate, berries, nuts and coffee. Many modern medicines, like aspirin, caffeine and morphine, are modeled after chemical compositions found in plants. If undiscovered or uninvestigated wildlife species disappear, it would disadvantage scientists trying to uncover new sources of inspiration for future vaccines and medications. Biodiversity also provides ecosystem services or benefits to people. These benefits include: hurricane storm surge protection, carbon sequestration, water filtration, fossil fuel generation, oxygen production and recreational opportunities. Without a myriad of unique ecosystems and their respective diverse plant and animal life, our quality of life may become threatened. Climate Impacts To many, the term “climate change” feels like a buzzword that encompasses a large amount of negative impacts. Climate means the average weather conditions in an area over a long period of time—usually 30 years or longer. A region’s climate includes systems in the air, water, land and living organisms. Climate change is the shift or abnormal change in climate patterns. As the planet warms quickly, mostly due to human activity, climate patterns in regions around the world will fluctuate. Ecosystems and biodiversity will be forced to fluctuate along with the regional climate, and that could harm many species. These climate change impacts are in part due to how we have altered land use. Turning natural areas into cities or agricultural fields not only diminishes biodiversity, but can make warming worse by chopping down trees and plants that help cool the planet. Changes in climate can also intensify droughts, decrease water supply, threaten food security, erode and inundate coastlines, and weaken natural resilience infrastructure that humans depend on. Politicians have proposed several solutions, plans and international agreements to tackle the long-standing issues that biodiversity loss and climate change present. In the meantime, we as individuals can take small actions in our daily lives to reduce our environmental impacts on the planet. Unplugging your unused appliances, changing to LED lightbulbs, carpooling, and participating in meatless Monday are all ways we can help to slow climate change. Growing native plants and staying informed about the origins and the ethics behind the products you purchase is another way you can help. These types of behavioral shifts can steer businesses and policy makers toward incorporating sustainable practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and halt biodiversity loss. Lauren Harper is an intern in the Earth Institute communications department. She is a graduate student in the Environmental Science and Policy Program at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs. Also read: Climate Change Is Becoming a Top Threat to Biodiversity - click here Habitat loss doesn’t just affect species, it impacts networks of ecological relationships - click here  BY JASON MARK (SIERRA CLUB) | JUN 24 2020 ON JUNE 30, 1864, Abraham Lincoln sat at his worktable, with its view of the half-finished Washington Monument and the Potomac River, and went through his daily routine of paperwork and correspondence. There were many issues to occupy the president's mind. The Union army had recently been walloped in the Battle of the Wilderness, Congress was debating a sweeping Reconstruction Act, and he had just dismissed his conniving treasury secretary. Among the minor matters on Lincoln's desk was a bill that Congress had just passed with scant debate, the Yosemite Park Act. The law promised to preserve for common enjoyment "the 'Cleft' or 'Gorge' in the Granite Peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains … known as the Yosemite Valley" along with the "Mariposa Big Tree Grove" of sequoias. Some 38,000 acres would be "held for public use, resort, and recreation … inalienable for all time." The president put his pen to paper and brought into being the first landscape-scale public park in history. Read on with this interesting article on our public lands. |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |