Dark-eyed junco; Credit: Chuck Jackson Dark-eyed junco; Credit: Chuck Jackson Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County While there are birds that live in Virginia all year round, many species are migratory –either leaving here in the spring for more northern climates where they breed, and returning to our area in the fall – or coming up from the south to breed here in Virginia and leaving in the fall to return to warmer climates during the winter. Most birds migrate at night. The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology created a marvelous tool – BirdCast - that tells you the total number of birds that fly over your county each night. This website features a Migration Dashboard with a bar chart that estimates the individual species that are moving overhead. Here in Madison County, BirdCast estimated that on September 17th, a total of 25,100 birds flew over Madison County! And it’s exciting as the list of birds includes species I have been recording in my daily eBird count. In Sunday’s BirdCast, the birds that are leaving our area included the Eastern Wood Pewee (Contopus virens), Yellow-Billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus), Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea), and the Blue-Gray Gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea). Of course, some of the migratory birds that will show up on BirdCast will be the ones who are returning for the winter. I am particularly looking forward to seeing the Dark-Eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). This little guy is a regular visitor to our bird feeders and usually spend their winter in flocks averaging in size from six to 30 or more birds. Scientists have tracked juncos and found that these birds will stay within an area of about 10 acres and often are the same birds that were in your yard last winter. How you can support migrating birds? There are some simple things that you can do to help migratory birds during their arduous journey south. Here are two easy steps to help migratory birds:

So check out who’s coming and going this year in your county on BirdCast – and if you’re not recording birds you see on eBird, do consider starting this fascinating activity. I bet you will enjoy knowing who’s coming and going in your area. Happy birding! Charlene

0 Comments

Cedar waxwing; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Cedar waxwing; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County The Cedar waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum)is a social bird that lives in Virginia all year round. Their population increases during the winter with migration from the north. Mostly seen in flocks, cedar waxwings move around looking for berries, their food of choice. They eat serviceberry, cedar berry, strawberry, mulberry, dogwood and raspberry. These birds eat in shifts, with one group eating first and then moving out of the way for the next group to come in. This is very different than most birds, who just try to grab what they can individually. Cedar waxwings are a major dispersing agent of seeds of various fruit species as their digestive system is so fast that the seed is expelled intact. They can also be responsible for significant damage to commercial fruit farms, which consider them a pest. During the summer before berries are ripe, cedar waxwings eat insects, including mayflies, dragonflies and stoneflies, which they catch on the wing. In late summer and fall, cedar waxwings have been observed eating overripe berries that have fermented in the sun, which causes the birds to become intoxicated. Because they can gorge on fruit, there have been instances when individual birds have actually died from intoxication. While I have never seen this “drunken” behavior, last year I saw a flock clean every single berry off of one of our large cedar trees that was laden with ripe berries. The habitat that attracts cedar waxwings includes woodlands of all types, particularly areas along streams. They are also observed in old fields and grasslands, farms, orchards, and suburban gardens that have fruiting trees or shrubs. Cedar waxwings spend much of their time in the tops of tall trees. Our farm is bordered by trees on two sides and the farm across the street is wooded – so we often see cedar waxwings in flight and in our trees. They are vulnerable to window collisions and being struck by cars as the birds feed on fruiting trees along the roadside. Cedar waxwings are “serial monogamous” – they form matings bonds that last one breeding season (from the end of spring through late summer). They reach reproductive maturity at one year and can live up to eight years in the wild. While categorized as a song bird, the National Wildlife Federation notes “their singing voices are nothing to sing about.” Their song is a high-pitched “sseee” call. The “waxwing” in its name refers to the brilliant-red wax droplets on their feathers which appear from after the second year. Scientists are not sure what the exact function is of brightly-color tips but assume it may be used to attract mates. So keep your eye out for these beautiful birds – they are fast flyers (up to 25 mph) so you just might miss them as they fly by. Happy birding! Charlene  Killdeer; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Killdeer; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County Carl Linnaeus gave the Killdeer its scientific name - Charadrius vociferus - in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae. Its common name comes from its shrill, two-syllable call: a shrill wailing “kill-deer” that is a distinctive way to identify it, even when it’s not in sight. Other 18th century naturalists had additional names for the killdeer, including “chattering plover” and “noisy plover," given it is in the plover family. Plovers are normally found near bodies of water: the ocean, lakes, and rivers. Killdeer can be found near water as well – but they are equally as common to pastures, lawns, golf courses, athletic fields, parking lots and even rooftops and airports! We have Killdeer on our farm all year around. We see them primarily on the perimeter between our lawn and our hay field. They are very active when the hay is cut, as it stirs up lots of insects! The Killdeer has a distinctive behavior used to protect its nest, called the “broken wing act”. It flutters along the ground in a show of injury, luring intruders away from its nest. This is an important behavior as the Killdeer’s nest is on the ground in an open area, providing the adults good visibility during incubation. Another behavior that has been observed in pastures is the Killdeer fluffing up its feathers to repel cows and horses from stepping on their nests.

The adult Killdeers sometime lines the nest with pebbles, grass, twigs or other bits of debris. The female Killdeer lays between 3-5 eggs and both male and female share incubation, which lasts between 24-28 days. The adults may soak their belly feathers in water to help cool the eggs in hot climates. The young leave the nest shortly after hatching. While the parents tend to them until they can fly, the young birds feed themselves. They are able to fly after about 25 days. Killdeer are mainly insect eaters. They search out beetles, caterpillars, grasshoppers, as well as spiders, earthworms, crayfish and snails. They will forage at night when the moon is full or close to full – both because of increased insect abundance and reduced predation during the night. You can sometimes hear them calling to each other on a moonlit night. Most of Virginia is warm enough for the Killdeer to stay here year round. Their main threat is pesticide poisoning since they forage on lawns and other open spaces that are often sprayed with toxins. These same pesticides also kill their main food source – insects. So avoid using pesticides and leave the bugs for the birds! Happy birding! Charlene  Tree swallows on the power line; Credit: Charlene Uhl Tree swallows on the power line; Credit: Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County Our farm attracts several members of the swallow family – barn swallows, purple martins and tree swallows. They are most active early in the morning and at dusk – or when my husband stirs up the bugs as he mows. The most dramatic of the three is the tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor)--both for its iridescent blue green back and brilliant white chest as well of the size of the flocks that arrive in mid-summer as they congregate for the fall migration. At this time of year, I easily see 50-75 swallows sitting on the electric lines that cross our field and line the driveway of our neighboring farm. These are the early migrators. The most I have counted this year is 250 – and when I recorded on eBird, I was “asking” to explain this high number. Last year the highest count I recorded was 500 swallows. It was later in the summer and closer to the time the majority of swallows had begun their migration Tree swallows can be found along coastal beaches, freshwater ponds and lakes and agricultural fields. They are voracious insect eaters and can be seen displaying their aerialist skills when a storm is brewing and the wind brings insects up above the ground. They eat all kinds of flying insects, as well as spiders and mollusks. The size of their prey ranges from smaller than a grain of sand to up to 2” long. They chase prey with acrobatic twists and turns, which is how they got the nickname “aerialist in tuxedo.” Virginia is in the southernmost area where tree swallows breed. Large numbers migrate deep into the northern part of Canada to breed. Tree swallows are cavity nesters, as we discovered when they commandeered one of our bluebird houses last year. And their nest was exquisitely lined with white feathers. They are known for traveling great distances to find dropped feathers to line their nests. They have also been observed playing with dropped feathers, chasing after them before taking them into the nest box. Nest predators are the same ones that frequently raid cavity nests: snakes, raccoons, bears, feral cats and the like. While they are not considered endangered, their populations have declined slowly over the last 50 years due to the disappearance of natural cavities. They have also shown a sensitive response to climate change. The average life of a tree swallow is 2.7 years. They have a low first-year survival rate – 79 percent do not survive that first year. The oldest tree swallow recorded was twelve years old. If the increasing numbers of tree swallows on our farm is any indication, their southern migration is starting. So keep an eye out for these delightful acrobats in the air! Happy birding! Charlene  Bald eagle; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Bald eagle; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County We infrequently see bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) fly over our farm, which is such a treat. I occasionally pick up their calls on the Merlin bird ID app, as well. There are woods on the north side of our farm where, according to several long-time residents, eagles have nested on a regular basis, though we have never found a nest ourselves. The ones flying over our farm are probably heading for the Rapidan River, which is about one mile “as the bird flies” from our farm. We have seen eagles along the Rapidan looking for their favorite food: fish. Since the favorite food is fish, you will often see them near lakes, rivers and ponds. They will also go after other birds’ catch. In addition to fish, they eat waterfowl, turtles, rabbits, snakes and other small animals, as well as carrion. Eagles were once listed as an endangered species in the United States. Pesticide use and hunting played havoc with their ability to raise their young. The pesticide, DDT, interfered with their ability to produce strong eggshells – resulting in thin shells that often broke during incubation or failed to hatch. The lead in ammunition is still often ingested by eagles when they eat a deer carcass--shot by a hunter who either couldn’t reach the dead deer or only retrieved the head as a “souvenir"-- which can lead to lead poisoning in the birds. Bald eagles nest and live all year within Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay has the densest breeding population of bald eagles in the continental United States – only Alaska has more than we do. William & Mary’s The Center for Conservation Biology has been counting raptors for 30 years. They estimate that our bald eagle population is somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 birds. Want to see bald eagles in Virginia? Here is a link to the six most likely state parks to spot bald eagles and some of the special events these parks offer related to eagles. In our area, you will frequently see eagles flying over and around the Blue Ridge Parkway. The bald eagle has been our national emblem since 1782. It has been revered by native peoples for far longer than that. Historians tell us that Benjamin Franklin was “rooting” for the American turkey to be our national emblem, not the bald eagle. Franklin was very disparaging in his correspondence, describing the bald eagle as “a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his living honestly [referring to the bird’s habit of stealing fish from other birds]…Besides he is a rank Coward”, referencing Franklin’s observation that a little bird could attack the eagle in defense of its nest and the eagle would leave. But the Second Continental Congress selected the bald eagle as the U.S. National Symbol on June 20, 1782. Immature eagles have a long “adolescence,” spending their first four years of life exploring different territories. Their wingspan of up to 7-1/2 feet at maturity allows them to fly hundreds of miles each day. Young birds born and tagged in Florida were found as far north as Michigan and birds from California have traveled to Alaska before settling down. Eagles have a much longer life span than many birds. Their life span in the wild ranges from 20-30 years. The oldest recorded bird in the wild was at least 38 years old. And they can be fascinating to watch. Bald eagles have been observed “playing” with objects such as plastic bottles and in one instance a witness recorded six bald eagles passing sticks to each other in midair. So here’s hoping we all see a few bald eagles this year! Happy birding! Charlene  Hummer approaching sugar water feeder; Credit: Charlene Uhl Hummer approaching sugar water feeder; Credit: Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County Ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) come to our sugar water feeders every year in Madison County. This year, we started to plant native flowers in one of our raised beds, including one of their favorites: bee balm (Monarda didyma). The sugar water feeders are within ten feet of these flowers. Our hummers regularly fly back and forth between the feeders and the flowers, almost like their “all you can eat” food bar. Hummers have outstanding spatial memory and can remember feeder locations years later. They are able to keep track of bloom peaks and remember which flowers they have visited. Scientists attribute these skills to the large portion of a hummingbird’s brain that is occupied by the hippocampus, an area dedicated to learning and spatial memory. Worldwide, there are over 360 species of hummingbirds and they are found only in the Americas. They can be found in a wide variety of habitats from desert scrubland to above tree line at 10,000 feet in the Andes. Unfortunately like many birds, habitat loss is threatening many species. The U.S has only 15 species; the Ruby-throated is the only hummer found east of the Great Plains. Ecuador has the largest number of species of hummers of any country: 130. The average life span of a hummingbird ranges from 3-5 years. The oldest know Ruby-throated “hummer” was a banded female that was captured (then re-released) in West Virginia in 2014 – it was least nine years and two months old. Here are some remarkable statistics on these tiny birds, whose amazing acrobatic flying skills are a big part of their attraction:

Here are some birding tips on how to attract hummers to your yard:

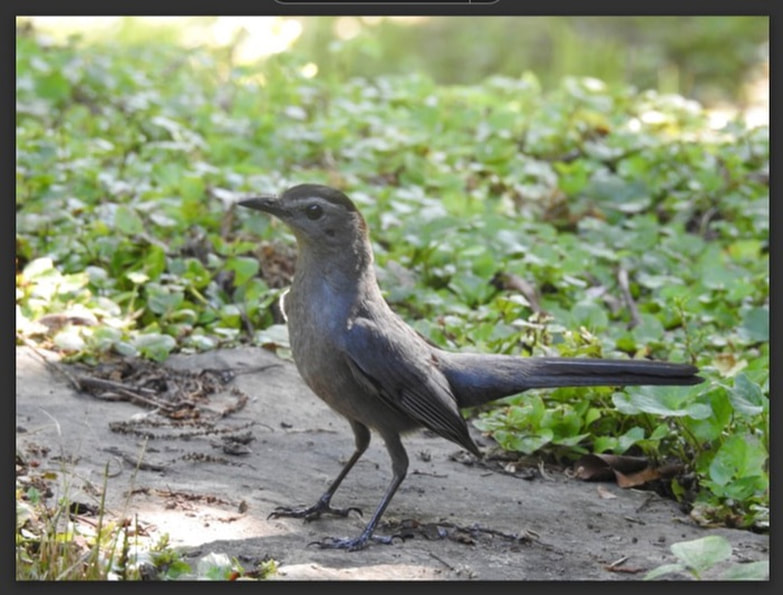

For more information and a list of top native hummingbird plants check out this website from the American Bird Conservancy. Happy birding! Charlene  Gray catbird; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Gray catbird; Credit: Deanne Lawrence Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County The gray catbird (Dumetella carolinenesis) is a migratory bird in our area, returning to Virginia by the last week in April and leaving in large numbers for more tropical climates in the last week of September and early October. While breeding, the catbird protects its young. During nesting season, it is very territorial. It will chase away other songbirds, sometimes even destroying their nests. So it’s no surprise that it doesn’t tolerate the brown-headed cowbird. There are 247 species of birds that end up caring for cowbird’s eggs and nestlings – but not the catbird! Catbirds are among the small number of birds (including blue jays, American robins and brown thrashers) that deftly reject cowbird eggs. If a cowbird introduces an egg into its nest, the catbird quickly breaks the egg and tosses it out. Catbirds inhabit a wide variety of shrubby habitats, including suburban backyards. The male singing in your backyard during mating season is likely to be the one that was there last year. Studies have found that a catbird returns to the previous year's nesting location place throughout its life. While its average life span is 2 ½ years, only about 60% of catbirds survive each year. The longest living catbird recorded was 17 years and 11 months old. The gray catbird’s voice is a reflection of this songster. A relative of the mockingbird, it copies the sounds of other species in its habitat. It is best known for the cat-like mewing calls from which its common name comes. I have heard stories of people who called the local animal control office, concerned about a cat in their backyard. But it turned out to be a catbird (how embarrassing was that!). We have several catbirds on our farm. I am fascinated to watch them sit on fence posts, jerking their long tails back and forth. Primarily ground-feeders, they flip leaves and other debris aside to find insects, including beetles, ants, caterpillars and grasshoppers. Catbirds also eat spiders, millipedes and wild berries. They are known to be “junk food” eaters, as well. Catbirds have been observed eating doughnuts, cheese, boiled potatoes and corn flakes! Their habit of pecking fruit (but not totally eating it) can make them unpopular with gardeners. But it’s worth a few piece of fruit to have this delightful bird be part of the birds around you. Happy birding! Charlene Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County I have always found the “roadside silhouettes” on the inside cover of Peterson’s "A Field Guide to the Birds East of the Rockies" to be an excellent bird identification tool. Even if the only thing you can see is the bird’s silhouette, it can narrow your choices very quickly. So I found it interesting that Roger Tory Peterson selected the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) for that position.

If you have ever heard a mourning dove, you can understand where its common name comes from - the mournful cooing made by both males and females. Its distinctive head bobbing as it walks is another clue to identifying this bird. Doves feed on the ground, swallowing seeds and storing them in an enlargement of their esophagus called the crop. Once the crop is full, a dove will fly to a perch to digest its meal. The record for ingested seeds is 17,200 bluegrass seeds in a single bird’s crop! Mourning doves are monogamous and often mate for life. They are known for making flimsy platform nests of twigs that often fall apart in a storm. The female usually lays two eggs and incubation takes just two weeks. Both adults feed their chicks crop-milk, which is regurgitated liquid that has been stored in the adult’s crop. This nutrient-rich liquid is used to nourish squabs (the name for young doves and pigeons). The mourning dove lives about two years and is one of our most common birds. It is usually found in open countryside and frequently seen roosting on telephone and electric lines. The only place you won’t see it is in deep woods. When it takes take off in flight, its wings make a distinctive whistling or whinnying noise. The oldest known mourning dove was at over 30 years old who it was shot in Florida in 1998. It had been banded in Georgia in 1968. The mourning dove is the most widespread and abundant game bird in North America. While every year hunters harvest more than 20 million, its population is actually increasing and is estimated to be around 350 million. Happy birding! Charlene Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County You have probably heard the Carolina chickadee’s song – “chickadee-dee-dee” – if you have a birdfeeder or trees in your yard or you have woods near your home. We have two pairs that consistently enjoy the food I put out for the birds on fence posts separating our farm from the neighboring farm to the west.  Carolina chickadee; Credit: Charlene Uhl Carolina chickadee; Credit: Charlene Uhl The Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis), which is in the same family as the Tufted Titmouse (Paridae), is widespread in Virginia and the most common chickadee in the state. Their preferred habitats include mixed and deciduous woods, river groves, shade trees and well-wooded suburbs. Chickadees are one of the first birds to use a newly placed bird feeder. They visit for sunflower seeds, peanut chips and suet. The chickadee will fly to the feeder, grab a single seed, carry it to a branch and hold the seed down with its feet. It hammers the shell open to get the meat inside. It then quickly returns to the feeder to get another seed. Their diet is mostly insects and spiders but they also eat seeds and berries, especially in the winter. Their acrobatic feeding habits are a delight to watch: they hang upside down and tilt their head and body up to reach insects on leaves and under tree bark. They sometimes take food while hovering and may fly out to catch insects in mid-air. Chickadees can be attracted to your property by offering a nest box or nest tube with a 1-1/4 inch entrance opening. Despite their small size, they are relatively fearless and are one of the species of birds that will commonly try to drive away predators such as hawks, owls and snakes. Like the titmouse, however, they are very vulnerable to predation by outdoor cats. The Carolina chickadee was among the birds named by John James Audubon when he was in South Carolina. The black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus)) is very similar in appearance but less seen in our state. Where the two species’ range come into contact, the Carolina chickadee and the black-capped chickadee will occasionally hybridize. Hybrids can sing the songs of either species and might sing something that is a blend of the two songs. A chickadee pair bond between a male and female can last for several years. During the winter chickadees band together in large flocks. The life span of a Carolina chickadee is 2-3 years. The longest-lived known was 10 years 11 months old and found in West Virginia in 1974. Bluebird update: We have a pair of bluebirds that have built a nest in our second nest box – and this morning I counted 4 beautiful blue eggs. It is such a joy to offer a “home” for a bluebird family on our farm each year! Happy birding! Charlene Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County

The “peter, peter, peter” call of the tufted titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) is often the first bird song I hear when I go out each morning to journal the birds that I see and hear. We have titmice in the woods across the street, in the woods that line our farm and we also get them on a regular basis at our birdfeeder. Titmice are non-migratory so I may take them for granted during the excitement of the return of the birds that fly south for the winter. But their perky crested head and their comfort in being around people reminds me of how much I value these special birds on our farm. While you will often see titmice at your bird feeder, they have a broad diet, 2/3rd of which is insects. They have special muscles in their legs that allow them to hang upside down to feed – so they often see insect eggs under leaves where other birds cannot. They are known for storing food in bark crevices and are very good at remembering the location of their different caches. You will often see them foraging with other small birds, including chickadees, kinglets, brown creepers and nuthatches. After breeding season titmice will join flocks that include other small birds – a frequent technique used by many birds as a protection from hawks. In addition to birds of prey, titmice are hunted by snakes, raccoons, and opossums. One of their worst enemies are house cats, as titmice are very comfortable around people and are frequent birdfeeder visitors. Titmice line their nests with fur they have plucked from other animals, including raccoons, opossums, mice, woodchucks, squirrels, rabbits and livestock. While they mate for life, their life span is short, averaging 2.1 years. The oldest titmouse recorded by scientists was 13 years old. So please keep your cats inside – you may be saving the life of a titmouse and other birds as well! Update on bluebirds that successfully nested on our farm: One of our nest boxes had 4 eggs, of which three hatched. These three successfully fledged. I recently had the opportunity to see the male bluebird teaching one of the fledglings to “hawk” for insects. The male sat close to the fledgling on the top of a fencepost. The male swooped down, snatched a small insect, flew back to the post, and fed the insect to the fledgling. The adult then flew down again, returned and he ate the insect (apparently trying to show the fledgling how it was done). Then the adult flew away, followed by the fledgling. So, I don’t know when the fledgling got the point of the lesson. Happy birding! Charlene  Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County It took me a while until I saw my first Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) on our farm. I was hearing them and picking them up on Merlin. But it wasn’t until recently that I actually saw one. They are often hidden in and under thick shrubs, where they sing discrete musical phrases, often repeating them twice. The male Brown Thrasher has the largest documented song repertoire of all North American birds, with over 1,100 song types. Some sources state that each individual has up to 3,000 song phrases, while others stated beyond 3,000. While not having as diverse a “song book” as the Northern mockingbird, thrashers are also noted for their mimicry. During the breeding season, the male's mimicking ability is at its best display. It can impersonate the calls of Tufted Titmice, Northern Cardinals, Wood Thrushes, and Northern Flickers. So you have to be careful: if you don’t actually see some of these other birds and their song comes up on Merlin - maybe it’s actually a very talented thrasher! Thrashers don’t have a long life span: only about 34% live through their first and second year, and about 50% make it through to their third year. The longest known lifespan in the wild is 12 years. The thrasher’s distinctive curved bill has been noted for its flexibility in catching quick insects. Scientists have determined that this flexibility is due to the amount of vertebrae in its neck, which exceeds giraffes and camels. Thrashers defend themselves by using their bill, which can inflict significant damage to species smaller than them, along with wing-flapping and vocal expressions. The name “thrasher” is believed to have come from the thrashing sound the bird makes when digging through ground debris. I have frequently seen their feeding behavior where they turn over leaves, small rocks and branches, looking for insects and nuts. Scientists have also found bones of lizards, salamanders, and frogs in the stomach of thrashers. So they have a very eclectic diet. The thrasher name is also thought to come from the thrashing sound that it makes when it is smashing large insects to kill and eventually eat them. When feeding, the Brown Thrasher can hammer nuts like acorns in order to remove the shell. Scientists have observed thrashers digging a hole about 1.5 cm (0.59 in) deep, place an acorn in it, and hit the acorn until it cracked – almost like a form of tool usage. So enjoy these talented song birds and the role they play in nature. Happy birding! Charlene Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County

I clearly recall the first view of a wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) on our farm. We had just moved into the house that we built and were sitting on the back porch when a female turkey rounded the corner and started to walk down toward the woods line at the bottom of the field. She seemed to stagger from side to side, almost like she was drunk. So of course I researched it. Apparently fruit-eating birds including turkeys can over-indulge in berries. While berries are a good source of food, when the fruit starts to rot a bird can get inebriated. According to the Audubon Society, “drunk” birds tend to stagger from side to side, don’t fly as well, and aren’t easily able to avoid obstacles in flight. So maybe that turkey we saw had eaten a few too many very ripe berries. She finally reached the wooded area and that was the last sight of a turkey we had until just recently. We now have 3-5 turkeys that walk out of the woods to the south of our farm, cross the road, and then feed along the margins of our farm. The turkey is the largest game bird in Virginia. We have friends who are hunters and they have told us our property is ideal for turkeys (we don’t hunt turkeys but like knowing we have the right habitat for them). Their favorite habitat is a mixed-conifer and hardwood forest. The land across the street from us fits the description of their habitat, as does the farm that abuts the back of our acreage. In addition to berries, we also have several large oak trees – and acorns are a favorite food of turkeys. Wild turkeys sleep in trees at night – so they have a choice of the woods across the street and the woods on our farm. The wild turkey was hunted nearly to extinction by the early 1900s, when the population reached a low of around 30,000 birds. But restoration programs across North America have brought the numbers up to seven million today. Turkeys can run at speeds of up to 25 miles per hour and fly as fast as 55 miles per hour. The life span of a wild turkey is 3-5 years. Birding tip: An organization called Birdwatching Bliss! offers lots of free advice, including how to use binoculars, what are the best bird field guides, available bird apps, and more. You can subscribe to receive information in your inbox each day. Happy birding! Charlene Uhl  White-breasted nuthatch taking seed; Credit: Charlene Uhl White-breasted nuthatch taking seed; Credit: Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County Nuthatches, affectionately known as the “upside down bird," are common in deciduous forests and wooded urban areas. Our farm offers them an ideal habitat: three sides of our farm are wooded, we have an abundance of nut-producing trees (its favorite food), and the hayfields offer plenty of insect meals (spiders being their favorites), as well. I have seen nuthatches at our birdfeeder, hanging upside down and poking their long beaks into the feeder. They also like to hang on the suet holder and fend off aggressive blue jays while snacking on the rich fat in the suet. We primarily have white nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis) but occasionally see a red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis). While watching these birds near the forest edge, I have seen them come for seed, then fly to the nearest tree and hide the seed in crevices – assumedly for later consumption. Sometimes they will gobble one or two seeds – then take one to hide – basically “two for now and one for later.” Like many small birds, their average life span is somewhat short: from less than one year to 3 ½ years. However nuthatches up to 10 years old have been recorded. The local population of nuthatches fluctuates widely from year to year. Scientists attribute this to the availability of seed during the winter. Nuthatches are able to walk head first down tree trunks. That is due to the structure of its feet. A nuthatch’s foot has one big toe that faces backwards, while its other three toes face forward. This helps them to see insects and insect eggs that other birds climbing up the trunk might miss. While they are one of the nosiest woodland birds in the early spring, they are relatively silent when breeding. I noticed this specifically this year. The nuthatches were “chortling” throughout the winter months. While I continue to see them every day, I have noticed they are not making any noise. It was like a switch was flipped off! According to Birds of Virginia Field Guide, nuthatches are frequently seen in mixed flocks with chickadees and Downy woodpeckers. They are all cavity nesters so maybe they take turns finding the right size cavity for their size. Birding tip: An excellent source of information on birds is Audubon’s Guide to North American Birds. This resource provides information on migration, conservation status, feeding behavior, diet, nesting and eggs, and recorded songs and calls. Check out the nasal "yank-yank” of a nuthatch so you’ll know when you hear it. Happy birding! Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County We have a lot of cardinals on our farm. They are regulars at our bird feeders and also out in the field. I will often see 10 or up to 20 cardinals on my morning walk. The male’s bright color is truly eye-catching. Surprisingly comfortable around people, cardinals feed and sing within a few feet of you if you remain still and quiet. That makes them easy to observe up-close and admire the male’s brilliant red plumage and the interaction between the male and female birds. Besides being the State Bird of Virginia, the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is also the state bird of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Not to be outdone by that alone, the cardinal is the mascot of two professional teams: the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team and the Arizona Cardinals NFL team. Cardinals are known by a lot of common names, including redbird, common cardinal, and red cardinal. An interesting thing about cardinals is that both the male and female sing. While 64% of female birds around the world sing, it’s more common in tropical areas. Cardinals are monogamous and stay together year round. Female cardinals sing as part of their strong instinct to defend their breeding territory. And females have more elaborate songs than males and may sing up to two dozen different tunes. During egg incubation (11 to 13 days), the male brings food to the female. Once the eggs hatch, the female varies her song to the male – either signaling the baby birds need food (“come to the nest”) or warning him not to come (she may have spotted a predator). Scientists have been able to isolate specific female songs and identify what she is trying to communicate to her mate.  Cardinals perched in cedar bonsai; Credit: Charlene Uhl Cardinals perched in cedar bonsai; Credit: Charlene Uhl Here are some other interesting facts about cardinals:

Birding tip: For a list of bird identification books and apps, check out BIRDA (https://birda.org). BIRDA is a birdwatching app and community aimed at people who want to deepen their connection with nature and join a community that can support their interest in birding. Happy birding! Charlene Uhl  Red-bellied woodpecker; Credit: Charlene Uhl Red-bellied woodpecker; Credit: Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County We have a healthy population of red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus) on our farm. They regularly come to our bird feeder and can be seen flying over the farm throughout the day. One of their favorite places to land is on the electric poles that cross our property. I don’t think they are finding any insects in those poles but they have a good view of the open areas and surrounding trees. So why isn’t the Red-bellied woodpecker called a Red-headed woodpecker? After all, the last thing you notice on its belly is the slight rose blush. The story is that the red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocecephalslus) was named first (and indeed its head and neck are bright red) so the name was already taken. The Red-bellied call is loud and frequently heard during the spring and summer. It could best be described as a loud trilling, descending in pitch. I love to research each bird I see on our farm: unique behaviors, their life span, what they eat, and aspects of their life. One of the things I found in researching the red-bellied is that it can stick out its tongue nearly 2 inches past the end of its beak. The tip is barbed and the bird’s spit is sticky (similar to a Pileated woodpecker), which allows them to snatch prey (primarily insects) from deep crevices in trees. I have seen them wedge nuts into crevices on top of one of our fence posts – then whack the nut into smaller pieces which they quickly consume. They are opportunistic feeders, eating berries, seeds, small invertebrates, as well as lizards, frogs, fish and bird nestlings. They even occasionally catch flying insects in the air. Like other woodpeckers, they may store nuts and seeds during the fall in crevices, to be eaten during the winter. The male red-bellied may excavate several holes, with the female selecting which one is completed and used. They may also use natural cavities, abandoned holes of other woodpeckers, or a nest box. In our area red-bellieds usually raise 2-3 broods each year. One of their major nest predators are European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Scientists have found that as many as half of all red-headed woodpecker nests in some areas get invaded by starlings. The life span of woodpeckers ranges from 4 - 11 years. The oldest known Red-bellied lived to over 12 years and was identified in the wild by his band. Birding tip: Birds are most active between dawn and 11 am. This is particularly the case in spring and early summer, when birds sing in the early morning. So get out there before your breakfast and you’re bound to see more birds than after lunch! Happy birding! Charlene Uhl |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |