Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) on garage rooftop; Photo: Charlene Uhl Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) on garage rooftop; Photo: Charlene Uhl Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County Following up on last week’s Bird Blog on blue jays, I wanted to share Atticus Finch’s quote on mockingbirds: “It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” Finch tells his daughter Scout. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us.” While this doesn’t totally exonerate Finch for his statement about blue jays, it does capture the special essense of the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos). Every year since we moved into our house here in Madison County, we have had a pair of mockingbirds that own the immediate land around the house. The male mockingbird begins singing early each morning in the spring. He has several favorite perches, including the weather vane on our barn, the peak over our garage and the two large holly trees on the east side of our house. He will frequently fly straight up from his perch, then back down – all the while singing loudly. He moves from one perch to another to another, singing a lovely medley of songs – and sometimes I think I actually recognize which bird he is mimicking (or not). Mockingbirds also mimic other sounds, including crickets, cats and even sirens! Once our pair of mockingbirds builds a nest, they actively chase other birds away. And they are very territorial overall – scientists and other birders have observed them attacking predatory birds, even bald eagles, when their territory is invaded. Stan Tekiela describes their mating behavior perfectly in Birds of Virginia: “Very animated, male and female perform elaborate mating dances by facing each other, heads and tails erect. They run toward each other, flashing white wing patches, and then retreat to nearby cover.” Birding tip: Mockingbirds eat seeds, insect, bugs and worms – and they will definitely visit your bird feeding area if you put out suet. But unlike woodpeckers, the mockingbird can’t hang upside down on the suet cage so they will perch on top of the feeder to have a snack. Happy birding! Charlene Uhl

0 Comments

The little things that we do every day have a huge impact on our natural world. It makes sense that native plant enthusiasts care about invasives, clean water, soil health, the warming climate, more intense weather patterns, even clean air…but what about dark skies?

Dark skies affect multiple natural processes. For example, many crops are dependent on insect pollination. If you like to eat, you care about insects and in turn, also dark skies. Insects also serve as a food source for many species. If you care about birds, you care about insects and also in turn, dark skies. Why should we do something about light pollution? Humans “around 80 percent of all—and more than 99 percent of people in the US and Europe—now live under light-polluted skies. In addition to direct lighting from urban infrastructure, light reflected from clouds and aerosols, known as skyglow, is brightening nights even in unlit habitats.” (Kwon, 2018) Many, truly do not know what unlit skies look like. In addition, insects are impacted by light pollution. The article “Light Pollution is a Driver of Insect Declines” discusses how artificial light serves as an evolutionary trap. Artificial light is a human-induced problem. Throughout ecological history, “most anthropogenic disturbances have natural analogs: the climate has warmed before, habitats have fragmented, species have invaded new ranges, and new pesticides (also known as plant defenses) have been developed. Yet for all evolutionary time, the daily cycle of light and dark, the lunar cycle, and the annual cycle of the seasons have all remained constant. insects have had no cause to evolve any relevant adaptations to artificial light at night.” (Avalon et al, 2020) Insects are attracted to the ultrabright unnatural lights and exhaust themselves before engaging in pollination or reproduction. The decline of insects lead to diminished food sources for larger organisms. Light pollution causes disorientation and exhaustion in migratory birds. Birds use energy stores to make long journeys. Studies show that “migrating birds were disoriented and attracted by red and white light (containing visible long-wavelength radiation), whereas they were clearly less disoriented by blue and green light (containing less or no visible long-wavelength radiation).” (Poot et al, 2008) The good news is that humans can put ecological practices in place to mitigate the impacts of light pollution. Further research shows that “artificial light at night impacts nocturnal and diurnal insects through effects on development, movement, foraging, reproduction, exhaustion and predation risk.” (Borges, 2022) It is estimated that light pollution is driving an “insect apocalypse” resulting in a loss of around forty percent of all bug species within just a few decades. There are multiple reasons to care about insects. We can make an impact on this serious problem. Community members can have their voices heard by participating in their local HOA meetings and completing surveys conducted by the local government in the comprehensive planning phase. By speaking out residents can weigh in on light ordinances in public spaces. Even talking to neighbors who are unaware of the problem can help. The International Dark Sky Association (https://www.darksky.org/) has great resources for educating yourself and others about light pollution. Virginia has five Dark Sky parks which are more than any other state East of Mississippi. The parks include Rappahannock County Park, Sky Meadows State Park, Staunton River State Park, James River State Park, and Natural Bridge State Park. The link to the parks can be found at https://www.darksky.org/our-work/conservation/idsp/finder/. Visiting Dark Sky parks and taking part in citizen science is an important way to help protect these amazing spaces for future generations to enjoy. Sycamore Grove Farm, Madison County  Groundhog; Photo: Charlene Uhl Groundhog; Photo: Charlene Uhl One of the most valuable techniques that I learned from a fellow ORMN birder – Lynne Leaper – is to make regular stops during your bird walk. Stop on a regular basis and just watch and listen. Lynne recommended 5 to 15 minutes and I have found this technique to be an amazingly effective way to see more birds and other animals in nature. On September 4th of last year, I was standing at one of the fence lines on our property. I regularly put a small amount of seed on the top of the fence posts and scatter some on the ground to attract birds. All the seed is usually eaten within 10-15 minutes and I move on. On this morning as I was standing very still and observing the birds, I saw something move to my right. It was a small, immature groundhog which had come out of nearby undergrowth. It may have been drawn to the bird activity. Since they also have a keen sense of smell, it may have smelt the seed. It cautiously walked to the scattered seed and began to eat. My slightest movement, however, sent it scurrying back into the thick brush. After several weeks of this behavior the groundhog became acclimatized to my presence and associated it with a food source. For the next month and a half, it came almost every day. October 17th was the last day I saw it. Since groundhogs have a lot of predators (including hawks, foxes, and coyotes, all of which we have seen on our property), I assumed it had been killed and eaten. Then this morning the groundhog appeared – over three months since I last recorded its presence – and started to eat seed just as it had last fall. It was a little more skittish but not like its first few weeks last fall. Apparently this groundhog had been hibernating and is just now coming out of its burrow. What I found after researching is that groundhogs, while primarily herbivores, are opportunistic eaters and will actually eat small birds. They can also climb trees! I have seen this more than once here on our farm. I look forward to journaling many more interesting observations during my morning bird walk. Birding tip of the day: Keep a written journal so you can look back and find information on birds’ behavior (when and if they migrated into or out of your area) and the behavior of other animals that are a part of the habitat. It will prompt you to use your observations to do research and learn more about your own property. I also record weather (cloud cover, air temperature, chill factor and humidity). I note if there is dew, frost, or snow on the ground and any other unique things (i.e. the date our field is cut, raked, and bailed). I started journaling during Basic Training Class and have found my observations to be an invaluable and specialized source for information on the natural world right here on our farm. Happy birding! Charlene Uhl

By Charlotte Hartley

Aug. 6, 2020 , 11:00 AM Science Magazine With their dazzling metallic hue, the blue fruits of the laurustinus shrub (Viburnum tinus), a flowering plant popular in gardens across Europe, are a sight to behold. But it’s what lies beneath the surface that’s caught the attention of scientists in a new study. Researchers viewed samples of the fruit tissue through an electron microscope to examine their internal structure. They found no blue pigment as is typical in other blue fruits such as blueberries—just layers and layers of blobs. These blobs turned out to be tiny droplets of fat, arranged in a manner that reflects blue light—a phenomenon known as “structural color”—the team reports today in Current Biology. Below the fat droplets lies another layer of dark red pigment, which absorbs any other wavelengths of light and intensifies the blue shade. The team verified these findings using computer simulations, confirming that this type of structure can indeed produce the precise shade of blue seen in the laurustinus. The striking color of laurustinus fruits may signify its high fat content to birds. Although structural color is well-documented in animals, including in vibrant peacock feathers and delicate butterfly wings, it is rarely observed in plants. What’s more, this is the first time that fats have been found responsible for this mechanism. The team suspects it may be more widespread, and hopes to identify this type of structure in other species. Posted in:

By drilling into lake bottoms, researchers collect mud cores with fossil pollen that reveal the history of plants.

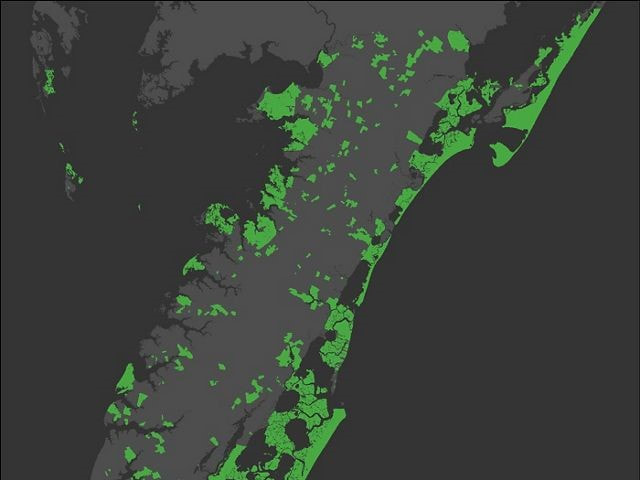

ANTHONY BARNOSKY By Elizabeth Pennisi Science Aug. 5, 2020 , 12:00 PM Recent human activity, including agriculture, has had a greater impact on North America’s plants and animals than even the glaciers that retreated more than 10,000 years ago. Those findings, presented this week at the virtual annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America, reveal that more North American forests and grasslands have abruptly disappeared in the past 250 years than in the previous 14,000 years, likely as a result of human activity. The authors say the new work, based on hundreds of fossilized pollen samples, supports the establishment of a new epoch in geological history known as the Anthropocene, with a start date in the past 250 years. “It’s hard to overemphasize how profound the effects of ending a glacial cycle are,” says Zak Ratajczak, an ecologist at Kansas State University, Manhattan, who was not involved with the work. “So for humans to have that kind of impact is pretty amazing.” For more than 10 years, researchers have debated when humans started to make their mark on the planet. Some argue agriculture transformed landscapes thousands of years ago, disrupting previously stable interactions between plants and animals. Others argue the launch of large-scale mining and smelting operations—seen in glacial records going back thousands of years—means the Anthropocene predates the industrial revolution. For geologists, however, the epoch starts with a different signal: nuclear explosions and a sharp uptick in fossil fuel use in the mid–20th century. But some skeptics suggest the ice ages have had an even greater effect on the world’s ecosystems. To test that idea, Stanford University paleoecologist M. Allison Stegner turned to Neotoma, a decade-old fossil database that combines records from thousands of sites around the world. Her question: When—and how abruptly—did ecosystems change in North America over the past 14,000 years? Climate-altering glaciers, which started their retreat roughly 20,000 years ago, pulsed back during a cold period called the Younger Dryas, from about 12,800 until 11,700 years ago. After that, North America abruptly warmed, marking the beginning of our current epoch, the Holocene. To answer her question, Stegner and colleagues looked at how vegetation shifted in locations across North America, using fossilized pollen to determine which species of plants were present at any given time. From 1900 records of mud cores drilled from lake bottom, Stegner found 400 with enough fossil pollen—and accurate enough dating—to analyze. She and her colleagues then tracked how the mix of pollen in each core changed over time, paying close attention to abrupt shifts. Such shifts can mark the transformation of an entire ecosystem, for example, when a grassland becomes a forest or when a spruce forest changes into an oak forest. Looking at 250-year intervals, the researchers ran two types of statistical analyses that separately picked out temporary and long-term disruptions. “Allison used some very creative and rigorous methods,” says Jennifer McGuire, a paleoecologist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved with the work. When the last ice age ended, forests and grasslands regrew across North America, creating a landscape that remained stable for thousands of years. But humans have changed all that, Stegner reports this week. Her team found just 10 abrupt changes per 250 years for every 100 sites from 11,000 years ago to about 1700 C.E. But that number doubled, to 20 abrupt changes per 100 sites, in the 250-year interval between 1700 and 1950. When the ice sheets of the Younger Dryas retreated, starting about 12,000 years ago, that number was 15. This suggests, Stegner says, that human activity starting 250 years ago—from land use change to pollution and perhaps even climate change—had more of an impact on ecosystems than the last glaciers. The researchers also analyzed whether some regions have changed more swiftly than others. Over the past 250 years the U.S. Midwest, Southwest, and Southeast have undergone massive shifts from forest, grassland, and desert ecosystems to agriculture and tree plantations, she says. In contrast, Alaska, northern Canada, and parts of the Pacific Northwest underwent more changes as the glaciers melted than in the past 250 years. “We already know plenty about climate change,” says Kai Zhu, an ecologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “This study adds land use change, [which] might accelerate climate change in altering plants at a continental scale.” That’s worrisome, McGuire adds, because plants are the foundation of an ecosystem. “This rapid turnover is a harbinger of the extinction risk and the overall ecosystem disruption that is impending,” she says. At another meeting session, she and student Yue Wang reported “very similar trends” after using pollen to examine how forests, tundra, deserts, and other biomes have bounced back from disruptions through time. Combined, the new work “eliminates any doubt” that humans have set off a new geologic epoch, Stegner says. doi:10.1126/science.abe1902  Earyn McGee in the field. Earyn McGee in the field. 7/29/2020 by Marsha Walton AAAS Herpetologist and University of Arizona Ph.D. candidate Earyn McGee’s research has her well prepared for obstacles like oppressive heat, treacherous terrain and even venomous animals. Her field research takes her to the Chiricahua Mountains of southern Arizona, where she’s determining the effects of stream drying on lizard communities for her doctorate research in conservation biology. This enables McGee a closeup look in studying lizards and their diet, and how the climate crisis may be altering it. She and the undergraduates she works with must first deftly catch the reptiles, weigh and measure them, then document their sex and overall health. It is demanding and unpredictable work. And it has sometimes been made riskier by unsettling encounters with police, whose actions imply that, as a young scientist of color, she does not have a right to conduct her field studies. “Where I work is pretty remote,” says McGee. “A lot of the time, it's Border Patrol, or some form of law enforcement stopping us [from working]. Last year, we had these military guys follow us into our site. A couple of days prior, we were out in the group with a whole lot of white people, we didn't have that same type of surveillance in the same exact spot,” says Already well known as a science communicator on social media, McGee counters such racist incidents with the message that the natural world belongs to everyone to love and to protect. And she stresses that excitement for nature can come at any point in time, whether hiking through a National Park or looking up at a tree in New York City. Her courage in speaking out went viral shortly after a white woman made racist threats against Black birdwatcher Christian Cooper in Central Park on May 25, 2020. McGee and several colleagues, who had already been communicating about academic and diversity issues, sprang into action. They created #BlackBirdersWeek. Photos and experiences soon flooded social media from all over the world. In interviews and podcasts during the week (May 31-June 5), scientists and naturalists shared examples of Black people, from birders to hikers to photographers, enjoying nature and outdoor spaces. The Central Park incident of racism, and the Twitter and Instagram responses to it, became another visible, widely shared facet in what’s become known as the U.S. Civil Rights racial injustice reckoning of 2020. Besides her activism aimed at adults, McGee also shares her knowledge about wildlife conservation with a younger audience. Lizards may be small, she says, but they can also be very swift and very clever. “[Catching] them the first time, depending on the lizard, can be relatively easy. But that next time when they see you coming, they're like, ‘Oh no, not this again,’ and they take off running,” she says. And she has some stories of these types of experiences she often shares on her social media accounts. “So I'm running after this lizard, sprinting. This lizard is really putting up a good chase. I'm hopping over logs and rocks and stuff. I caught her, but before I did, I took a picture and I told people on Twitter the story of what happened,” says McGee. Her followers were intrigued by the elusive lizard story. Since June 2018, thousands of curious students and adults regularly scour the photos on her informal Twitter quiz, using the hashtag, #FindThatLizard. After locating the reptiles, McGee then shares details about their camouflage, eating habits and survival skills. She’s heard from many science teachers who now start their classes off with this quest. McGee says lizards are an easy sell to get kids hooked on science. In her outreach work, she shares fun facts about lizards, such as some lay eggs, some give live birth, others can even clone themselves. And what’s not to love about a Gila monster, asks McGee? “People pay money to come from all around the world for the hope of seeing this lizard (the Gila monster). It's one of few venomous lizards in the world, and compounds from its saliva have been used to create medical treatments for diabetes. So, lizards are cool,” she says. McGee’s activism and fearlessness led to her recognition as one of the younger AAAS IF/THEN® Ambassadors. In her role as an ambassador, McGee shares with young girls her expertise on the power of social media for women and underserved minorities in STEM fields. She also hopes to introduce young girls to career paths in natural resources. Still, McGee knows other types of outreach are needed to improve diversity and equity in STEM. While she says there is currently a lot of activism on her own campus to combat racism and xenophobia, McGee says institutions need to do more to assist Indigenous Mexican-American and undocumented students. When her studies are complete in about a year, McGee plans a career as a science communicator, perhaps hosting a nature show on TV. And her quest for social justice will stay closely tied to her career path. “I really want to be able to create pathways for Black, Indigenous, other people of color to enter into natural resources fields, and even if they don't want to do it as a job, maybe find it as a new hobby. So that's really what I hope to accomplish in the future,” said McGee.  Jeremy Miller Guardian Thu 21 May 2020 06.30 EDT Deer, bobcats and black bears are gathering around parts of Yosemite national park typically teeming with visitors. Earlier this month, for the first time in recent memory, pronghorn antelope ventured into the sun-scorched lowlands of Death Valley national park. Undeterred by temperatures that climbed to over 110F, the animals were observed by park staff browsing on a hillside not far from Furnace Creek visitor center. “This is something we haven’t seen in our lifetimes,” said Kati Schmidt, a spokesperson for the National Parks Conservation Association. “We’ve known they’re in some of the higher elevation areas of Death Valley but as far as we’re aware they’ve never been documented this low in the park, near park headquarters.” The return of pronghorns to Death Valley is but one of many stories of wildlife thriving on public lands since the coronavirus closures went into effect a month and a half ago. In Yosemite national park, closed since 20 March, wildlife have flocked in large numbers to a virtually abandoned Yosemite Valley. More than 4 million visitors traveled to Yosemite last year, the vast majority by way of automobile. On busy late-spring days, as visitors gather to see the famed Yosemite, Vernal and Bridal Veil Falls, the 7.5-mile long valley can become an endless procession of cars. But traffic jams seem a distant memory as the closure approaches its two-month mark. Deer, bobcats and black bears have congregated around buildings, along roadways and other parts of the park typically teeming with visitors. One coyote, photographed by park staff lounging in an empty parking lot under a rushing Yosemite Falls, seemed to best capture the momentary state of repose. A handful of workers who have remained in Yosemite during the closures, who have been able to travel by foot and bike along the deserted roadways, describe an abundance of wildlife not seen in the last century. “The bear population has quadrupled,” Dane Peterson, a worker at the Ahwahnee Hotel, told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s not like they usually aren’t here … It’s that they usually hang back at the edges or move in the shadows.” Similar behaviors have been documented in other national parks including Rocky Mountain, in Colorado, and Yellowstone, in Wyoming. “Without an abundance of visitors and vehicles, wildlife has been seen in areas they typically don’t frequent,” said the National Park Service spokesperson Cynthia Hernandez, “including near roadways, park buildings and parking lots, spending time doing what they usually do naturally: foraging for food”. The human-free interregnum is rapidly coming to an end, however, as the park service ramps up its phased reopening. While Yosemite, Death Valley and a number of other California national parks remain closed, on Monday, Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks – which collectively received nearly 8 million visitors in 2019 – reopened their gates for the first time since late March. To protect visitors and staff, the park service has hired seasonal workers to disinfect high use areas and installed plastic barriers at tollbooths, visitor centers and permit desks. But few if any protective measures have been put in place for wildlife. The consequences of the reopenings may be especially hard on young animals born in the calm of the closures, according to wildlife experts. “Individuals who have lived in the national park area will likely readjust pretty quickly to the return of recreators after quarantine,” said Lindsay Rosa, a conservation scientist with Defenders of Wildlife. “But newcomers, particularly juveniles born this spring, may take a bit longer to learn since they haven’t yet had the opportunity to encounter many humans.” Visitors to the re-opened parks should be particularly wary of amphibians, says Rosa, many of which are beginning their migration to breeding grounds. “[For them], roads remain a particularly fatal obstacle.”  Shenandoah Salamander Plethodon Shenandoah By Linda Duncan The topic of my student presentation for my Master Naturalist class was the Shenandoah Salamander. Unable to present the class with a live specimen I created a Papier Mache’ sculpture, about 15 times larger than the actual Shenandoah Salamander. Read about the Shenandoah Salamander (an endangered species) and Linda's creation of Sal (Here) Terrence McCoy

Washington Post, April 15, 2020 RIO DE JANEIRO — It's not easy being a baby sea turtle, hatching into a human's world. Curious children, leashless dogs, oblivious joggers: The dangers are many. Some never complete their postnatal dash to the ocean. But in recent days, environmentalist Herbert Andrade has watched hundreds of baby turtles mosey their way toward the water along Brazil’s northeast coast, unmolested by people or pets, unencumbered by anxiety. The beach is empty. People, fearful of catching and spreading the coronavirus, are inside. But outside, Andrade sees a natural world blooming. “The whole world is under risk,” said Andrade, environmental manager for the city of Paulista. “But this was a moment of happiness. It was a feeling that nature was transforming itself.” For centuries, humans have pushed wildlife into smaller and smaller corners of the planet. But now, with billions in isolation and city streets emptied, nature is pushing back. Wild boar have descended onto the streets of Barcelona. Mountain goats have overtaken a town in Wales. Whales are chugging into Mediterranean shipping lanes. And turtles are finally getting some peace. Buffalo walk on a mostly empty highway in India last week. (Getty Images) While some stories of animal invasion that have gone viral have been fake — turns out elephants didn’t get drunk on Chinese corn wine and pass out in a tea garden — the apparent resiliency of the natural world is leavening a global tragedy with brief moments of wonderment. For people. And, apparently, for animals, too. “The goats absolutely love it,” said Andrew Stuart, a resident of Llandudno, Wales. He saw the goats stroll into town one recent night, and has watched since then as they’ve availed themselves of its offerings. They’ve munched on windowsill flowers. Convened in parking lots. Strutted down emptied streets. “They keep coming back, multiple times per day, 10 to 15 of them,” he said. “They’re taking the town back. It’s now theirs. Nothing is stopping them.” But beyond the short-term benefits that human quarantines have brought the animal kingdom, conservationists say the pandemic could be an opportunity to push for more environmental protections and create a safer world for animals. An infrequently uttered word is beginning to sneak into conversations among conservationists and animal rights activists. “I am hopeful,” anthropologist Jane Goodall told The Washington Post. “I am. I lived through World War II. By the time you get to 86, you realize that we can overcome these things. One day we will be better people, more responsible in our attitudes toward nature.” A growing body of research has suggested that the risk of emerging diseases, three-quarters of which come from animals, is exacerbated by deforestation, hunting and the global wildlife trade, particularly in exotic or endangered species. One of the major vehicles for the transmission of novel diseases from animals to humans are wildlife markets, in which exotic animals are kept in cramped and unsanitary conditions. They have been linked to both severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and covid-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus. Now countries around the world are under growing pressure to act. China, whose insatiable demand for animal parts drives much of the global wildlife trade, has taken the extraordinary step of banning the consumption of wild animals, and may do the same for dogs. Vietnam, another country with a large demand for animal products, said it intends to follow suit. The U.N. biodiversity chief has called for a global ban on wildlife markets. So have 60 members of the U.S. Congress. More than 200 of the world’s leading conservation groups have asked the World Health Organization to take action against the wildlife trade. A World Wildlife Fund survey of 5,000 people in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia found 90 percent supported government closures of unregulated wildlife markets. “Humans are extraordinarily selfish,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a Brookings Institution scholar who studies wildlife trafficking. “If they start dying, they will start taking actions to minimize their dying. The most impactful and consequential legislation always comes after the health risks.” The impacts of the closures and crackdowns, if they persist, will be global, undercutting the demand that fuels illegal wildlife trafficking, an illicit trade valued at more than $23 billion annually. The ripple effects of enforcement in Asia could be felt as far away as Latin America, where jaguars and turtles are hunted and killed to meet demand in China. “Asian traders call it the Latin tiger,” Felbab-Brown said. “They are using jaguar bones and teeth to produce elixirs. . . . It’s picked up a lot in Latin America.” Mountain goats roam the streets of Llandudno, Wales, last month. The goats, who live on the rocky Great Orme, are occasional visitors to the seaside town, but a councilor told the BBC the herd is now drawn by the lack of people and tourists. (Christopher Furlong/AFP/Getty Images) But analysts say the pandemic also heightens potential dangers for animals. Poverty and hunger, exacerbated by lockdowns and disruptions in food supplies, may drive more people to hunt. “And that’s okay,” said Joe Walston, a senior official with the Wildlife Conservation Society. “If people are put in a position of poverty, and we have failed providing economic alternatives, they should be able to do that.” More concerning, advocates say, is the possibility that people could abandon their pets, out of the mistaken fear they can spread the virus, or because they can no longer afford to feed them. “It is more likely to increase pet abandonment,” said Marco Ciampi, president of Brazil’s Humanitarian Association of Animal Protection and Well-Being. “And the fake news is terrible. But even with this, animals will be in a more safe position, if we listen to the call of animals: ‘We are here, and if the environment is friendly, we are friendly, too.’ ” “It’s an amazingly magical moment,” he said. “There are peacocks in the streets.” Bruce Borowsky, a videographer in Boulder, Colo., was walking through the main pedestrian strip of the college town last week when he experienced that magical moment. Up near the top of a tree, beside a building, he spotted a mountain lion, asleep, back paws hanging down. Down below, Pearl Street, which normally teems with restaurant patrons, shoppers, and University of Colorado students, was a “ghost town.” Nothing was waking up the mountain lion anytime soon. “I’ve lived in Boulder for 30 years, and I’ve never seen a mountain lion before,” Borowsky said. “And I’m a filmmaker and am outdoors constantly. Animals are sensing that people aren’t around much and are coming out more. “We’re waiting for the bears to come out of hibernation and see how brazen they get.” Along Brazil’s northeastern shoreline, Andrade is also seeing sights he has never witnessed. He has cared for endangered sea turtles for more than a decade, and has seen all sorts of calamities befall them. Artificial light along the beach especially confuses the turtles. They mistake it for the water’s reflection, wander off toward it and die along the way. “For every thousand,” he said, “only one or two reach adulthood.” For years, he has tried to teach people about the fragility of baby sea turtles — an ongoing effort he compared to a boxing match. He has erected protective areas around their nests. He has held events to show children why they’re special. Life was getting better, safer for turtles. But nothing compared to this: an empty beach. For him, the beauty of it ached. “It was a surreal sensation,” he said. “You see nature living out its role in this way. . . . Things fit together. We saw nature birthed without human interaction.” March 27, 2020 by PamKamphuis

The Piedmont Virginian By Joe Lowe When it comes to abundance, the stars we see at night (approximately 5,000) shine dimly compared to the number of plant and animal species in Virginia’s Piedmont, which may exceed 20,000, although the real number — if ever known — is almost certainly larger. If that’s surprising, it’s because the “big” species we usually see, like oak trees and deer, take up a lot more space in our minds than they do on a species roster. In reality, “small” organisms — fungi and insects, among others — represent life’s greatest diversity, numerically dwarfing their larger counterparts. These organisms, big and small, are never far. On a short walk, we might come across dozens or hundreds. Pill bugs, sumac bushes, and crows, for example, may not seem terribly interesting or consequential, but the Piedmont’s flora and fauna — known collectively as its biodiversity — are an absolute necessity for the area’s human residents. Working together, plants and animals keep soils fertile, pollinate fruits and vegetables, produce fresh air, keep water clean, and help regulate climate. In short, they maintain a local life-support system without which the Piedmont would be a wasteland. Although most of the region may look like a model of rural health, we know that its plants and animals are under intense pressure. How? Because species like the Rusty-patched Bumblebee and Purple Fringeless Orchid are telling us in the clearest way possible: by disappearing. And they are not alone. Once common birds like the Common Nighthawk, Northern Bobwhite, and Eastern Whip-poor-will are now scarce in the region. Other species are gone. Since European colonization, Virginia has likely lost 72 species. In the Piedmont, another 59 are in serious decline — more than at any other time in modern history. Some of these species range outside of the Piedmont and their downturns can’t be blamed entirely on local changes. Their dwindling numbers are symptomatic of a much larger problem. Human alterations to the planet have forced extinction rates into overdrive, reaching levels not seen for the last 65 million years. And if trends continue, half the world’s total plant and animal species could be facing extinction by the end of the century. This wouldn’t be a loss just for wildlife enthusiasts, it would be a loss for everyone who depends on traditional economic and agricultural practices. Like biodiversity itself, threats to flora and fauna vary by continent and region. In the Piedmont, there are many challenges, but experts agree that several rise above the others. Habitat Loss, Fragmentation, and Degradation During winter, local Wood Ducks spend months living in frigid water, impervious to conditions that would send us scrambling for shelter. Even so, we dismiss the feat with four words, “They’re used to it.” But what happens when “it” — the circumstances that animals and plants are accustomed to — change? Like us, their survival depends on a few basic requirements: food, water, shelter, and space. And when these conditions – known as habitat — deteriorate or disappear, they follow suit. In the Piedmont, this happens in several ways. The first, and most obvious, way is when habitat is destroyed for new construction. While some counties do a better job of restricting urban expansion than others, this has not stopped forests and fields from being converted into roadside malls, roads, and residential areas. New homes, of course, aren’t without greenspace; they have yards. But for wildlife, a well-manicured lawn, at best, offers little food, water, or shelter; at worst, it poses mortal risks when sprayed with pesticides, which kill pollinators like butterflies and bees. Multiplied across the landscape, habitat loss has a fragmenting effect, breaking large forests and grasslands into a patchwork of small, distinct spaces. In the Piedmont, these usually take the form of isolated woodlots among surrounding farms. Although they may look fine, these forests lack the critical mass necessary to maintain long-term health. They’re susceptible to invasive species and other threats, and slowly break down as their natural communities deteriorate. Habitat health isn’t just a forest issue. Given that farms cover much of the Piedmont, agricultural practices have a big impact on local biodiversity. Eastern Meadowlarks and many other grassland birds, for example, rely on local pasture for nesting sites. This can have deadly results, though, when fields are hayed before chicks fledge. Similarly, removing streamside forests and allowing cattle to graze and defecate in waterways is detrimental for aquatic species. The Dwarf wedgemussel, a freshwater mollusk, is already gone from Fauquier County, and eleven other mussel species are threatened in the region. Invasive Species If you think you know your neighbors well after a few years, imagine the relationships local plants and animals have after living together for millennia. These connections helped form a community that has flourished, in part, thanks to a natural system of checks and balances, maintaining native populations at sustainable levels. The Piedmont’s natural equilibrium, however, is in growing trouble thanks to the human-introduction of invasive species that don’t play by local rules. These species outcompete natives and multiply to nightmarish levels, upending the ecological fabric of our natural communities. They come in many forms. A fungus from China, the Chestnut blight, decimated the Piedmont’s Chestnut trees in the first half of the twentieth century. More recently, insects like the Emerald Ash-borer and Wooly Adelgid have begun killing off our Ash and Eastern Hemlock trees. Meanwhile, more than 80 species of invasive plants have besieged the Piedmont, sending destructive ripples throughout the food chain. For example, while caterpillars feast on native plants, they can starve on invasives. This means lower reproduction rates for Eastern Bluebirds and other songbirds that depend on caterpillars to feed their chicks in invasive-dominated areas. Making things worse, invasive plants have found unlikely allies among our native White-tailed Deer. Thanks to human influence, deer populations have surged across the Piedmont in recent decades — and their impact has been dramatic. Not only do deer inadvertently spread the sticky seeds of some invasive plants, their voracious grazing threatens the health of native forests and plants. Protecting the Piedmont’s Biodiversity Despite the challenges, local citizens and organizations are actively working to protect the Piedmont’s biodiversity. Piedmont landowners have put nearly 500,000 acres under conservation easement, protecting it from development. But there is still more to do and plenty of ways to make an impact. Create and Improve Habitat Most of the Piedmont is privately owned, which means that landowners have a large role to play in protecting biodiversity. Doing so is probably easier than you think. For starters, next time you feel compelled to tidy your lawn, relax. By leaving leaves, saving snags, and mowing a little less, you can improve habitat for local wildlife. If you want to do more, remove invasive species and plant natives. Remember, when it comes to protecting biodiversity, everything counts: a single oak tree can feed and provide shelter for hundreds of species. If you’re interested in a conservation easement or would like to improve wildlife habitat on your property, the Piedmont Environmental Council can help. If you own a farm and would like to protect streams and improve livestock health, reach out to the local Natural Resources and Conservation Service or John Marshall Soil and Water Conservation District for support. The Virginia Department of Forestry can also provide stewardship recommendations to improve the health of your woodlot. Learn More Many organizations offer educational programs for children or adults. These include The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Friends of the Rappahannock, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy. For more intensive training, sign up for the Virginia Master Naturalist training program. The Virginia Native Plant Society provides excellent online resources and the Virginia Department of Forestry offers identification guides to local trees and shrubs. Volunteer Locally Volunteering to support land stewardship and citizen science efforts is a great way to get involved. Opportunities are available with The Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, Friends of the Rappahannock, Loudoun Wildlife Conservancy, Blue Ridge Center for Environmental Leadership, and Bull Run Mountains Conservancy. Special Report:

JEFF COX, APR 7, 2020,Horticulture online A few decades ago, I wrote Landscaping with Nature (Rodale Press, 1991), a book about gathering inspiration for home landscaping by going into wild nature and noting what was aesthetically pleasing, then finding ways to bring those inspirations home. I didn’t know it at the time, but I only had half the story. It takes an incredible 6,000-9,000 caterpillars to raise one clutch of chickadees. The other half is to create those natural home landscape designs with native plants. There are so many good reasons to do so, chief among them is the lifeline that native plants throw to native fauna, especially insects and birds. A true champion of this notion is Douglas Tallamy, a professor in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware. “You might think we gardeners would value plants for what they do. Instead, we value them for what they look like,” he says. He has worked to educate us on the merits of native plants and conservation that starts in our gardens through his books Bringing Nature Home (Timber Press, 2009) and Nature's Best Hope (Timber Press, 2020). Most of us know some of the things that our plants do: produce oxygen, build topsoil, prevent erosion and flooding, sequester carbon dioxide, buffer extreme weather, clean our water and shade our houses. But it’s their ability to turn sunlight into food for all of earth’s creatures that’s supremely important, especially in the context of local ecologies. One summer, Professor Tallamy did a simple experiment. He counted the number of caterpillars on a native white oak in his yard and compared it to the number of caterpillars he found on a nearby ornamental Bradford pear, an Asian native. “I found 410 caterpillars on the white oak comprising 19 different species, and only one—an inchworm—on the Bradford pear,” he said. Why such a huge difference? Native insects have co-evolved with native plants. To avoid predation, plants load their tissues with nasty insect-repellant chemicals, but the native insects have developed ways to de-fang those chemicals, usually with enzymes. The Bradford pear is a relative newcomer, and there are no insects that have yet evolved the ability to eat it—except maybe that inchworm. “In the past,” he says, “we thought this was a good thing. After all, Asian ornamentals are planted to look pretty, and we certainly didn’t want insects eating them. We were happy with our perfect pears, burning bushes, Japanese barberries, golden rain trees, crape myrtles and all the other foreign ornamentals.” Then he pointed out the ecological cost. “If you have a pair of nesting chickadees, watch what they bring to the nest to feed their hatchlings: mostly caterpillars. It takes an incredible 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars to raise one clutch of chickadees. “What we plant in our landscapes determines what can live in our landscapes. An American yard dominated by Asian ornamentals doesn’t produce nearly the quantity and diversity of insects needed for birds to reproduce. We have 50 percent fewer birds than 40 years ago, and some 230 species of North American birds are at risk of extinction,” he said, citing the 2014 State of the Birds Report. “By the way,” Professor Tallamy says, “you might assume that my oak was riddled with unsightly caterpillar holes, but not so. Since birds eat most of the caterpillars before they get very large, from 10 feet away the oak looked as perfect as the Bradford pear.” He adds that since almost all native insects have specialized relationships with native plants, planting non-natives reduces biodiversity. For example, very few insects other than the juniper hairstreak butterfly can eat the tissues of the eastern red cedar without dying. So if we don’t include cedars in our landscapes, we lose the hairstreak. “And the only host for the great fritillary butterfly is the native violet,” he points out. “When violets are mowed down, we lose the fritillaries. And if we lose the insects, including spiders and moths, we lose amphibians, bats and rodents. Even the fox eats insects—25 percent of his diet is insects.” In his book written with Rick Darke, Living Landscapes: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, Professor Tallamy tells the story of the Atala butterfly, a native of South Florida that once thrived on its sole host plant, Zamia pumila, a native cycad. The butterfly disappeared as the cycad was harvested to near extinction to make starch from its roots. But in the mid-1970s, landscape designers rediscovered it as a valuable evergreen that could take drought and heat. As it started showing up in more and more South Florida yards, the Atala butterfly returned. “Maybe it had been harbored in the Everglades or somewhere, but adding that single plant brought the butterfly back,” said Professor Tallamy. Horticulture columnist Jeff Cox writes from his home in northern California. The Virginia Coast Reserve is the longest stretch of wilderness along the nation’s entire Atlantic coastline. As it embarks on its next half-century, the Virginia Coast Reserve stands out as one of the most important living laboratories in the world, having piloted community-based conservation, contributed landmark migratory bird research and pioneered techniques for restoring critical habitats such as oyster reefs and seagrass meadows, the Virginia Coast Reserve continues to produce groundbreaking science and innovative conservation. Read about it HERE.

By Elizabeth Preston © 2020 The New York Times

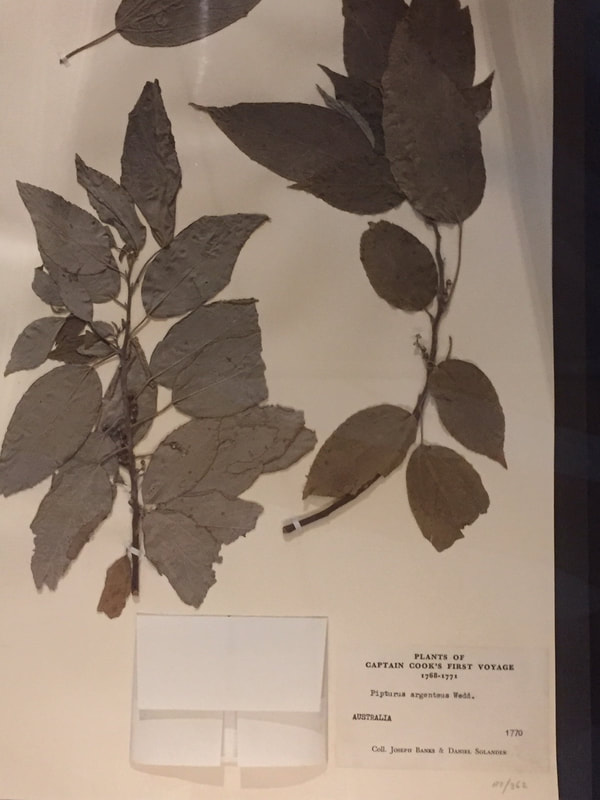

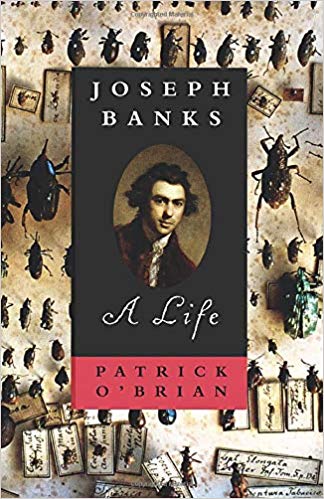

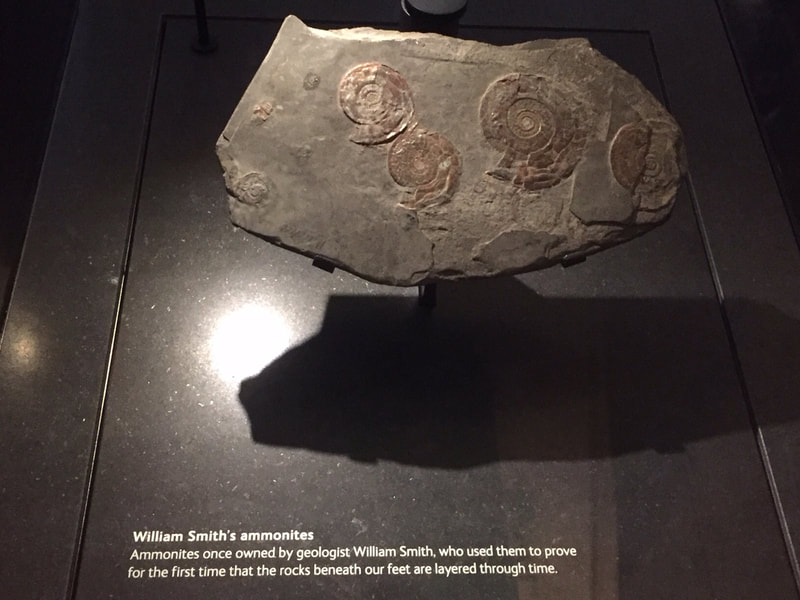

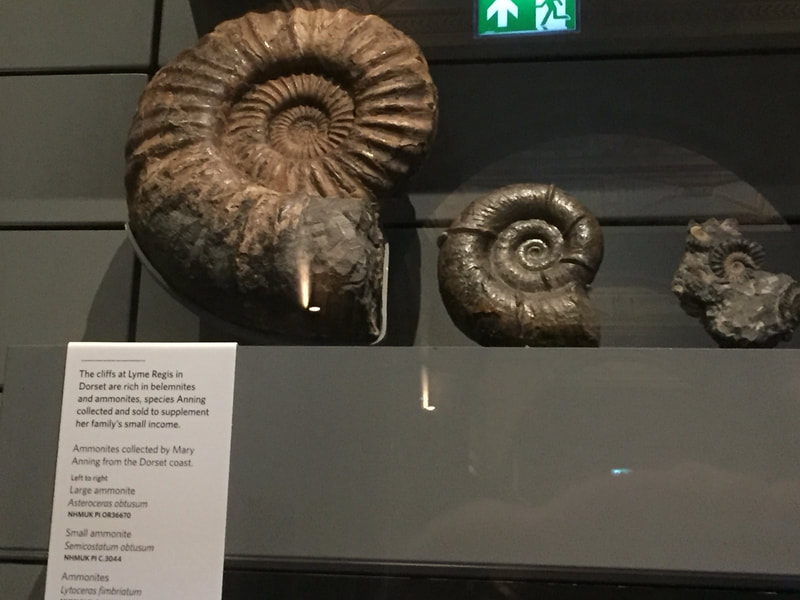

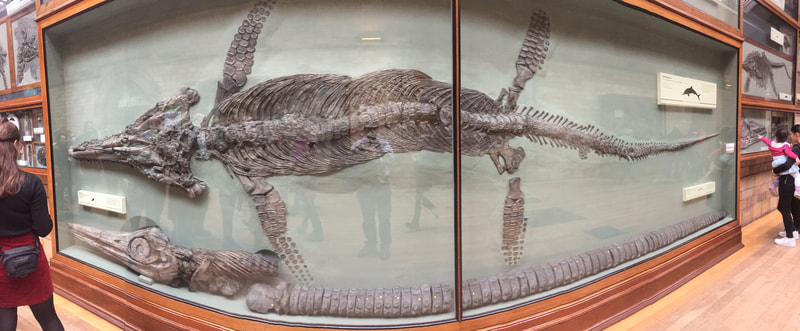

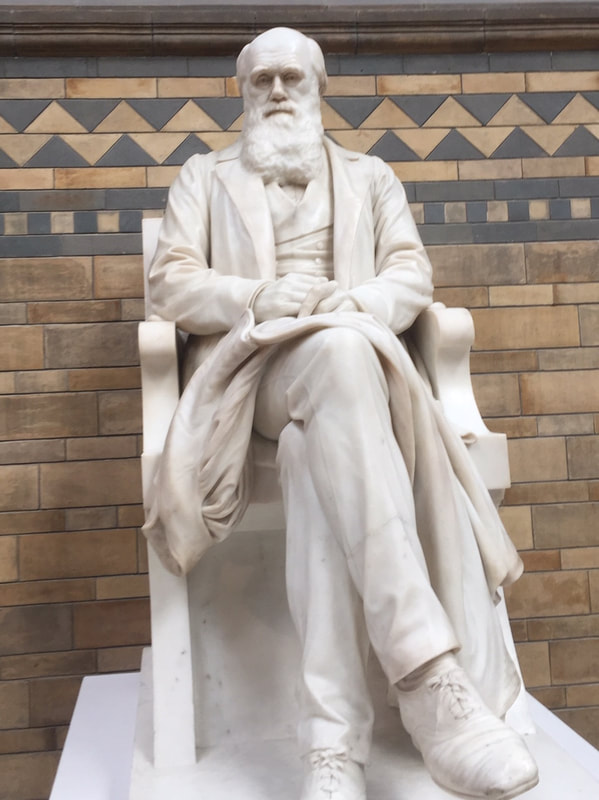

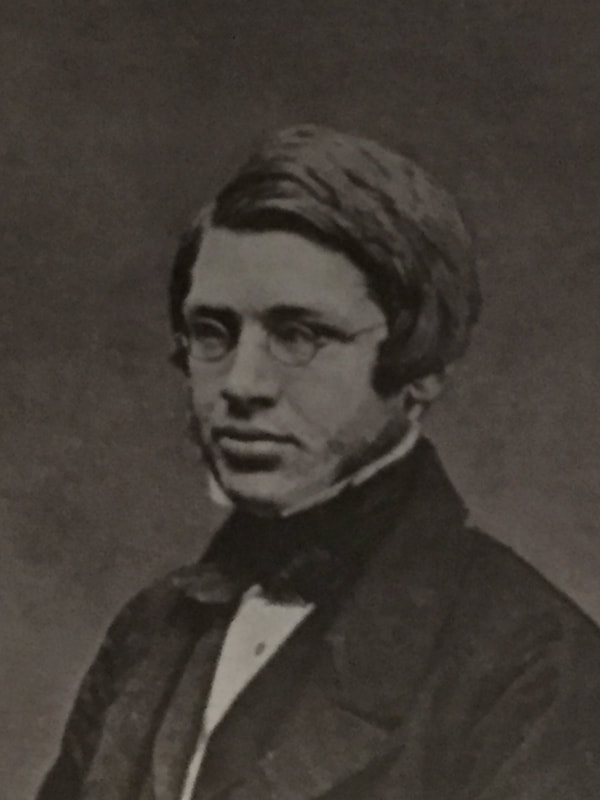

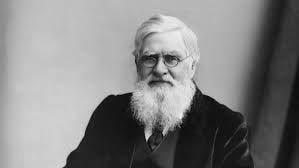

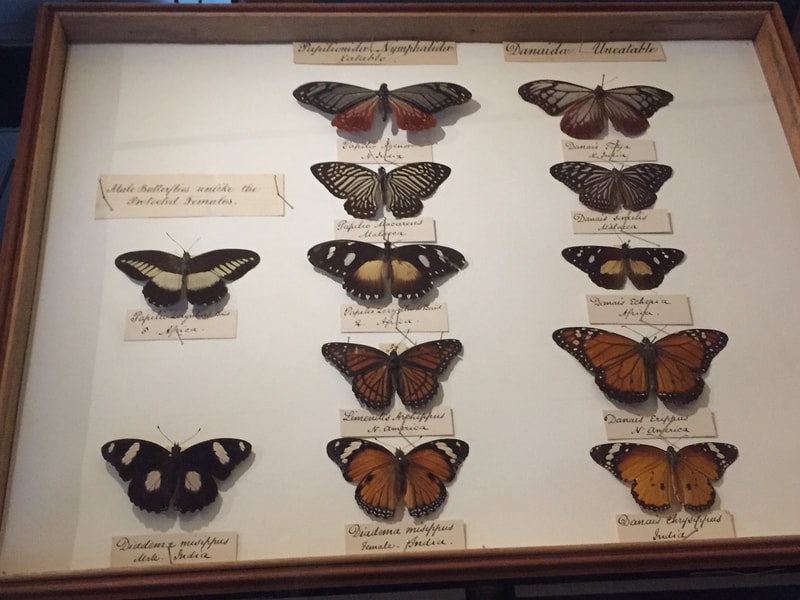

03.02.20 Are humans the only animals that caucus? As the early 2020 presidential election season suggests, there are probably more natural and efficient ways to make a group choice. But we're certainly not the only animals on Earth that vote. We're not even the only primates that primary. Any animal living in a group needs to make decisions as a group, too. Even when they don't agree with their companions, animals rely on one another for protection or help finding food. So they have to find ways to reach consensus about what the group should do next, or where it should live. While they may not conduct continent-spanning electoral contests like Super Tuesday, species ranging from primates all the way to insects have methods for finding agreement that are surprisingly democratic. Meerkats As meerkats start each day, they emerge from their burrows into the sunlight, then begin searching for food. Each meerkat forages for itself, digging in the dirt for bugs and other morsels, but they travel in loose groups, each animal up to about 30 feet from its neighbors, says Marta Manser, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Nonetheless, the meerkats move as one unit, drifting across the desert while they search and munch. The meerkats call to one another as they travel. One of their sounds is a gentle mew that researchers refer to as a "move call:' It seems to mean, "I'm about ready to move on from this dirt patch. Who's with me?" In a 2010 study, Manser and her colleagues studied move calls in a dozen meerkat groups living in the Kalahari Desert in South Africa. Groups ranged from six to 19 individuals. But the scientists found that only about three group members had to mew before the whole party decided to move along. The group didn't change direction, but it would double its speed to reach better foraging grounds. Biologists call this phenomenon - when animals change their behavior in response to a critical mass of their peers doing something - a quorum response. Manser thinks quorum responses show up in human decision-making, too. "If you're in a group and somebody says, 'Let's go for a pizza; and nobody joins in, nothing's going to happen;' she said. But if the pizza craver is joined by a couple of friends, their argument becomes much more convincing. Honeybees In the spring, you may discover a swarm of bees dangling from a tree branch like a dangerous bunch of grapes. These insects are in the middle of a tough real estate decision. When a honeybee colony splits in two, a queen and several thousand workers fly away from a hive together. The swarm finds someplace to pause for hours or days while a few hundred scouts fan out to search for a new home. When a scout finds a promising hole or hollow, she inspects it thoroughly. Then she flies back to the swarm, still buzzing on its tree branch. Walking on the swarm's surface, she does a waggling, repetitive dance that tells the other bees about the site she found - its quality, direction and how far away it is. More scouts return to the swarm and do their own dances. Gradually, some of the scouts become persuaded by others, and switch their choreography to match. Once every scout agrees, the swarm flies off to its new home. In his 2010 book "Honeybee Democracy;' Thomas D. Seeley, a Cornell University biologist, writes that we can learn a lesson from the bees: "Even in a group composed of friendly individuals with common interests, conflict can be a useful element in a decision-making process:' African wild dog Like pet dogs, African wild dogs spend some of their time enthusiastically socializing and some of it lazing around. Members of a pack jump up and greet one another in high-energy rituals called rallies. After a rally, the dogs may move off together to start a hunt - or they may go back to resting. In a 2017 study, researchers discovered that the decision to hunt or stay seems to be democratic. To cast a vote for hunting, the dogs sneeze. The more sneezes there were during a rally, the more likely the dogs were to begin hunting afterward. If a dominant dog had gotten the rally started, the pack was easier to persuade - just three sneezes might do the trick. But if a subordinate dog started the rally, it took a minimum of 10 sneezes to prompt a hunt. The researchers note that dogs might actually cast their votes via some other hidden signal. The sneezes could help the animals clear out their noses and get ready to sniff for prey. Either way, the wild dogs end their achoo-ing with a decision they all agree on. Baboons Primates, our closest relatives, have provided lots of material for researchers studying how groups make decisions. Scientists have seen gibbons following female leaders, mountain gorillas grunting when they're ready to move and capuchins trilling to one another. Sometimes the process is more subtle. A group may move across the landscape as a unit without any obvious signals from individuals about where they'd like to go next. To figure out how wild olive baboons manage this, the authors of a 2015 paper put GPS collars on 25 members of one troop in Kenya. They monitored the monkeys' every step for two weeks. Then they studied the movements of each individual baboon in numerous combinations to see who was pulling the group in new directions. The data showed that any baboon might start moving away from the others as if to draw them on a new course - male or female, dominant or subordinate. When multiple baboons moved in the same direction, others were even more likely to come along. When there was disagreement, with trailblazing baboons moving in totally different directions, others would eventually follow the majority. But if two would-be leaders were tugging in directions less than 90 degrees apart, followers would compromise on a middle path. No matter what, the whole group ended up together. Ariana Strandburg-Peshkin, an animal-behavior researcher at the University of Konstanz in Germany who led the baboon study, points out that unlike in human groups, among baboons no one authority tallies up votes and announces the result. The outcome emerges naturally. But the same kind of subtle consensus-building can be part of our voting process, too. "For instance, we might influence one another's decisions on who to vote for in the lead-up to an election, before any ballots are cast;' she said. by Jeff Stehm On a trip to London's Natural History Museum this week, I had the opportunity to capture some photos of the early naturalists that lead the way. Joseph Banks (1743 – 1820) was an English naturalist. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage (1768–1771), visiting Brazil, Tahiti, and after 6 months in New Zealand, Australia, returning to immediate fame. Below is a photo I took at the Natural History Museum of one of Joseph Banks' herberium sheets from that voyage with Cook - 350 years old....amazing! He is credited for bringing 30,000 plant specimens home with him; amongst them, he discovered 1,400. He help found and held the position of president of the Royal Society for over 41 years. William 'Strata' Smith (1769–1839) was an English geologist, credited with creating the first detailed, nationwide geological map of any country. At the time his map was first published he was overlooked by the scientific community; his relatively humble education and family connections prevented him from mixing easily in learned society. Financially ruined, Smith spent time in debtors' prison. It was only late in his life that Smith received recognition for his accomplishments, and became known as the "Father of English Geology". A fascinating book about Smith is Simon Winchester's The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology Mary Anning (1799–1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for important finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis in the county of Dorset in Southwest England. Her findings contributed to important changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth. An enjoyable historical fiction book about Mary Anning is Tracy Chevalier's Remarkable Creatures Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882) needs little introduction as a naturalist. His co-discovery of evolution by natural selection with Alfred Russel Wallace (see below) is well-known. Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 – 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator.[1] He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural selection; his paper on the subject was jointly published with some of Charles Darwin's writings in 1858.This prompted Darwin to publish his own ideas in On the Origin of Species. Like Darwin, Wallace did extensive fieldwork; first in the Amazon River basin, and then in the Malay Archipelago, where he identified the faunal divide now termed the Wallace Line, which separates the Indonesian archipelago into two distinct parts: a western portion in which the animals are largely of Asian origin, and an eastern portion where the fauna reflect Australasia. He was considered the 19th century's leading expert on the geographical distribution of animal species and is sometimes called the "father of biogeography". |

Have a blog or blog idea?

Let us know (click) Other Blogs

VA Native Plant Society - click Brenda Clement Jones - click John Muir Laws' Blog - click Megan's Nature Nook - click Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Blog Administrator:

Kathleen A. VMN since 2018 |